Ukraine reports looting of Kherson museums by Russian troops

Before leaving the liberated city, the occupiers loaded valuable works for relocation to Crimea, where 10,000 pieces are being kept for “protection” in Simferopol

Before leaving the Ukrainian city of Kherson, occupying Russian forces loaded up priceless works belonging to the city’s two main museums and, in an orderly manner, carted them away in trucks and buses in the direction of Crimea. This has been confirmed to EL PAÍS by Alina Dotsenko, director of the Kherson Art Museum, which along with the Kherson Regional Museum was looted by the departing troops.

Similar stories have emerged from other areas that have been occupied by Russian troops: some point to destruction and some to plunder, and at times to the sensation that behind the façade of the former the latter may be hidden. “The Russians entered Kherson on March 1. They came to the museum but initially they did not touch anything. We lied to them by saying that our collection had been evacuated and for two months we managed to keep them at bay,” Dotsenko told EL PAÍS from Kyiv. “The Russians came back later, dressed in civilian clothes, but armed,” adds the director, who this week is embarking on a trip to Kherson to review the state of the museum now that Moscow’s forces have withdrawn from the city.

“When the Russian troops arrived, the museum was closed because we were carrying out restoration work. Our collection was packed and stored in a special locked storage room, which was inside the building,” Dotsenko explains. “On May 4, they [the occupying authorities] called me and proposed setting up an exhibition for May 9, to coincide with Victory Day [the anniversary of the end of World War II]. I explained to them that the museum had been closed for repairs and that the objects from our collection were no longer there. I also told them that I did not want to associate with the occupation authorities.

“They told us that they had come to liberate us from the radical nationalists and they asked me why I did not follow the example of my colleague, the director of the Regional Museum, who had received them with a bouquet of flowers and voluntarily handed over her collection.

“Accusing me of acting disrespectfully to the authorities, who of course were going to be here forever, they summoned me to the Prosecutor’s Office the following day. I knew that meant they would take me to the basement, a place from where there was a danger of floating down the Dnipro...” says Dotsenko.

That night the director fled Kherson and three days later she reached Kyiv by taking backwoods routes. Her colleague from the Regional Museum, who had welcomed the Russians “with flowers,” had disappeared, as had three staff members at the Kherson Art Museum who, according to Dotsenko, would have collaborated with the Russians and given them access to the collection.

“On October 31, the first trucks appeared next to the museum. By then, they had been loading the Regional Museum’s collection for over a week, under the supervision of its director, who is now a suspect in the investigations being carried out by Kyiv”, says Dotsenko. The loading operation at the Art Museum lasted until November 4. The vehicles did not form a column but left one by one as they were filled, Dostenko adds.

Of the collection of 14,000 catalogued artworks at the Kherson Art Museum, some 10,000 were relocated to the Central Museum of Tavrida in Simferopol, Crimea, its director Andrei Malguin confirmed to EL PAÍS on Monday. “We have 10,000 pieces and we are inventorying them. The Crimean Ministry of Culture arranged for us to keep them here until they tell us otherwise,” said Malguin, according to whom the works are in his museum for “protection” from war damage and are being kept “in the concert hall, because that is the only place big enough.”

“The collection belongs to the Kherson Art Museum and we will return it to them when our superiors tell us to,” he added. “Our task is to ensure that they are not lost or damaged.” When asked whether the return of the pieces to Kherson is dependent on whether the city is under Russian or Ukrainian control, Malguin evaded the answer and reiterated that the decision lies with the authorities. “We do not get into politics,” he concluded.

“This is a huge loss, because these museums [in Kherson] told the story of southern Ukraine,” says Hana Mamonova, a journalist currently working on documenting war crimes, including crimes against culture.

The importance of the Kherson Art Museum is that it destroyed Moscow’s propaganda narrative that southern Ukraine is Russian. In that museum there were pieces from the 17th century to the present day, including a collection of icons painted in Ukraine, which in part are all that has remained of churches destroyed during the Soviet era,” Mamonova says from Kiyv. There were also works by representatives of Russian realism and the Peredvizhniki movement. The museum’s collection included canvases by Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900), Zinaida Serebriakova (1884-1967), Konstantin Makovsky (1839-1915), Ivan Kramskoi (1837-1887), Mykola Pymonenko (1862-1912) and Tetyana Yablonska (1917-2005), among others.

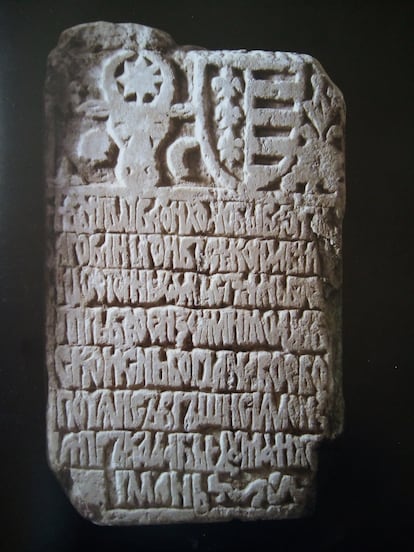

The collection of the Kherson Regional Museum has been transferred to the The Museum of Chersonesos, near Sevastopol in annexed Crimea, according to museum sources in Sevastopol and Kyiv. Of particular importance in this collection are the archaeological pieces that document the history of the northern Black Sea, where ancient civilizations including the Scythians and the Greeks settled. Among the missing objects are those from the city of Olbia, which flourished at the mouth of the Dnipro River in the 6th century BC, as well as several 15th century inlaid slabs from the fortress of Belgorod on the Dniester River near Odesa.

Cases of looting have also been reported in Melitopol, where the mayor of the city said the Provincial Museum, where Scythian-era gold was kept, had been ransacked. One of the greatest losses for the cultural heritage of Ukraine was the museum dedicated to the Greek-born landscape painter Arkhip Kuindzhi in Mariupol, which was burned down in a bombing raid. Kuindzhi (1840-1910) was a native of the city and one of the most important landscape artists of his time.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.