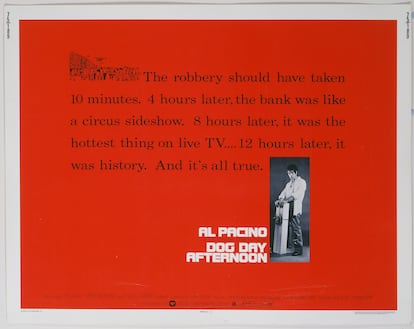

A true crime, an empathetic kidnapper and Al Pacino: How ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ made history

Fifty years after its premiere, it is still remembered as a brave, intelligent and emotional film, one of the pearls of New Hollywood and a highlight in the career of one of the big screen’s biggest stars

Heists that take hostages usually end badly and the one that took place on a sweltering August afternoon in 1972 at a bank in Brooklyn, New York, was no exception. One of the perpetrators, Salvatore Naturile, a 19-year-old Italian-American with a blond mustache and tattoos, was killed in the act while the mastermind behind the crime, John Wojtowicz, survived the FBI raid, served time in a Pennsylvania prison and sold the rights to his story to Warner Bros. for $7,500.

This is how Dog Day Afternoon began to take shape, a classic of cinematic dirty realism that was released in September 1975 and now celebrates its 50th anniversary. The main star, Al Pacino, now 85, recently gave an interview to The Guardian in which he says that “It hits you, seeing all those people in Dog Day. Can you imagine how you feel? Wow. It’s like a dream. You’re dreaming. You have a dream of someone and you’re so happy about the dream and then you wake up and they’re not there any more? They don’t even exist – in three dimensions anyway.”

Al Pacino is the only member of the cast still with us along with Chris Sarandon. The others, including John Cazale, Charles Dunning, Penny Allen, Carol Kane and James Broderick, have all passed away.

Al Pacino considers that Dog Day Afternoon has stood the test of time due to its being ahead of its time in so many ways. He highlights its corrosive sense of humor, its denunciation of police brutality and the unscrupulousness of the tabloid press, its honest and empathetic portrayal of the relationship between a bisexual man and a transgender woman, beyond stereotypes and malicious caricatures.

The veteran actor recognizes that all these virtues were already very clearly appreciated in the first draft of Frank Pierson’s script, which he had the opportunity to read in January 1974. However, when the producer, Martin Bregman, and the director, Sidney Lumet, offered him the lead role, Pacino decided to turn it down: “He told me he wanted me to do it, and I had read it and thought it was well-written but I didn’t want to do it,” Pacino recalls. “I was in London at the time and I thought, I’m running out of gas. I don’t know if I could do this again.”

The role sounded emotionally demanding; three months of intense filming under the orders of a perfectionist like Lumet and the formidable challenge of putting himself in the shoes of a human being as complex and contradictory as John Wojtowicz.

The script was based on the Life magazine article, The Boys in the Bank, published a few weeks after the robbery. The article described Wojtowicz as a small, nervous, charismatic, brown-skinned guy who was physically reminiscent of Al Pacino and Dustin Hoffman. Bregman and Lumet wanted Pacino, with whom they had already worked a couple of years earlier on Serpico, but his refusal made them consider Hoffman as an alternative.

Hoffman was the perfect spare wheel for a project with potential, but which needed a star on board to stay afloat. By then, both Pacino and Hoffman – the Italian-American from New York and the Jew from L.A. – were beginning to politely detest each other. They had a good relationship, but the press insisted on comparing them, and some producers considered them practically interchangeable.

Pauline Kael described Pacino as a Hoffman copycat and Roger Ebert was baffled by Hoffman’s efforts to look more and more like Pacino. A New York businessman, Alexander H. Cohen, even offered to organize a charity boxing match between the two at Madison Square Garden, a duel for supremacy between the two heavyweights of Hollywood that Pacino elegantly turned down. As he told Far Out magazine: “I said to Cohen, ‘Let me just tell you straight out: Dustin will beat me. He works out. He’ll knock me out.’ I thought Alexander would be better off asking Meryl Streep to fight me instead. But then I got a little worried. Shit, what if she wins? Luckily, the fight never got off the ground.”

Given that context, Pacino realized that if the role went to Hoffman it would cause a damage to his reputation he could ill afford. After a long period of trial and error, Pacino agreed to reread Pierson’s script and began to soak up the peculiar story of John Wojtowicz and his botched assault on the Brooklyn branch of Chase Manhattan bank.

Pacino was thrilled that Wojtowicz had acted out of love; the crime was meant to secure the thousands of dollars his partner, Elizabeth Eden, needed to complete the transition from male to female. He was also seduced by the peculiarity of a story light years away from the classic plots of perfect heists sabotaged by chance and he was intrigued that Lumet intended to inject a touch of social satire and dark comedy into the tale.

Bregman and Lumet were also good friends of Pacino’s. Lumet had helped Pacino deliver one of the best performances of his career with Serpico, and the role of the other robber was going to be played by John Cazale, a magnificent actor and practically a brother. As if that were not enough, the script turned the main character into a very desirable role: an incompetent criminal, but also a modern-day Robin Hood. A poor idiot, but also a champion of sexual diversity. A clueless guy who began by showing himself willing to kill as many hostages as necessary only to end up fraternizing with them and giving them a couple of dozen family pizzas. Pacino finally sensed that here was an individual that would be interesting to play.

The actor got involved in the final stretch of the casting process, shielding Cazale who was about to be ditched at the last minute because he was 39 – 20 years older than the character he was going to play – and enrolling a handful of actors and actresses with whom he had already worked in off-Broadway theater productions.

Lumet and Pacino then agreed that the entire cast would spend three weeks rehearsing in the summer of 1974. During those sessions, as Pacino told The Guardian, the project was on the verge of derailing again: “For some reason, I felt as though I didn’t know who the character I was playing was. I kind of left that out of the rehearsals or something. I don’t know what happened but I knew when I saw something on the screen I said: no. I saw I didn’t have a character so I thought, what am I doing, where am I, who am I, where am I going?” He thought about quitting, and leaving the job to someone more capable than he was of tuning in to John Wojtowicz’s psyche.

After a particularly frustrating session, he went home, and “drank half a gallon of white wine, which I don’t usually drink, for some reason and spent the whole night finding a character within myself from the script,” as he told The Guardian.

The next day, he showed up to rehearsals transformed. Lumet thought he was pushing himself too hard and was about to have a nervous breakdown. But what was really happening was that the character had finally gotten inside him: “I was becoming somebody else, I think. I was becoming the guy that’s in the film. I don’t know to this day if I was kidding myself or what. But I did go through that and it helped me.”

The last setback that the project had to face in its pre-production process was Wojtowicz’s refusal to have his name used in the film. Despite the fact that he had already collected his $7,500 and had given a third of that amount to Elizabeth Eden, he considered that the script took excessive licenses and that only around 30% coincided with what actually happened.

Martin Bregman tried to meet with him in prison and even offered him the possibility of joining the process as an external advisor. But Wojtowicz distanced himself by demanding more money and threatening legal action. So the producers chose to rename the character. He became Sonny Wotzik, allowing more freedom to Pacino who no longer had to resemble the person who had inspired him in every way.

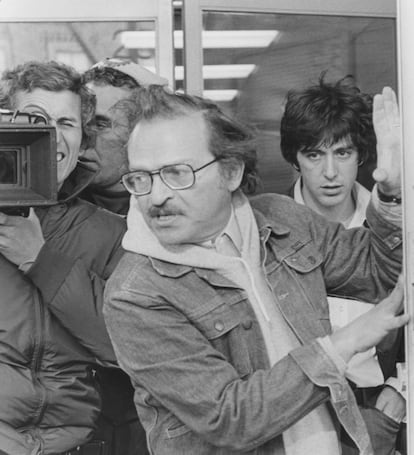

Summer in the city

Filming began in September 1974 with the outside shots of a New York in the middle of an intense heat wave. These included the traffic around Times Square, bridges, beaches, decrepit corners of the Brooklyn periphery and the Manhattan skyline. With those images, Lumet composed a dazzling visual collage to which he added an Elton John song, Amoreena, which sounds slightly distorted through the radio of the robbers’ car. He then locked the crew in an abandoned mechanic’s workshop that had been converted into a bank office, and that was where most of the film was shot.

The cameramen used roller skates and wheelchairs to move more fluidly around the set and give the film a feeling of naturalness and dynamism. Much of the material from the first week of filming had to be reshot, however, because Pacino was still working on his character and made two crucial decisions: to take off the sunglasses and shave the mustache he had sported in the first few takes.

He also refused to kiss Chris Sarandon who played the role of Leon, inspired by Elizabeth Eden, because he thought it would have been sensationalist. In his opinion, the robber and his transgender girlfriend should express their love for each other without physical contact. At the last minute, Lumet opted for the only scene in which they appear together to be a largely improvised telephone conversation, to avoid – always according to Pacino’s demanding criteria – the homosexual clichés included in Pierson’s script.

The film’s most memorable line of dialogue was also improvised; the moment when Pacino shouts “Attica!” before a fervent crowd, alluding to the riot that took place in the New York prison of that name in September 1971 and that the authorities cracked down on with such force that 43 prisoners died. Pacino explained that the reaction of the crowd of extras gathered on the set was genuine: for them too, Attica was the burning symbol of police brutality and its devastating effects.

The film ended up being released on September 21, 1975. It got rave reviews and grossed around $56 million in a year of blockbusters such as Jaws, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Return of the Pink Panther and The Rocky Horror Picture Show. It also got six Oscar nominations and a gong for best screenplay at the 1976 Hollywood Academy Awards. Even more important is that today we remember it as a brave, intelligent and emotional film, one of the pearls of New Hollywood, of the splendid filmography of its director and of the career of that indomitable perfectionist, Al Pacino, committed to his profession to almost insane extremes.

As for John Wojtowicz, the 20 years he got for refusing to plead guilty and agreeing to a lesser sentence would become just six. Released in 1978 for good behavior, he gave several interviews, joined an association for the defense of gay rights and cheekily applied for a job as a security guard in the same branch he had robbed. His relationship with Elizabeth Eden did not survive his years in prison, but they remained in contact and Wojtowicz was present at the funeral of Eden, who died of AIDS in 1987.

In 2013, the posthumous documentary The Dog was released in which Brooklyn’s Robin Hood was finally able to tell his side of the story. In it, he was portrayed as an arrogant and fickle narcissist who, according to his own testimony, began to sleep with men because his sexual appetite was infinite and women could not satisfy it. Nor did he show the slightest respect for Salvatore, his dead accomplice, or for the people he held for 14 hours at gunpoint and who ended up feeling an affection for him only attributable to Stockholm syndrome. Very little to do, in short, with the Sonny Wotzik of the silver screen, the one who was about to lead a civic insurrection to the cry of “Attica!” and shared a fraternal salami pizza with his hostages.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.