Readers prefer ChatGPT poems over Shakespeare and Sylvia Plath

In a new study, participants with no expert knowledge in poetry were also unable to distinguish whether the verses were created by a person or a machine

“Oh, how I revel in this world, this life that we are given / This tapestry of experiences, that shapes us into living / And though I may depart, my spirit will still sing / The song of life eternal, that flows through everything.” These are the opening lines of a poem generated by ChatGPT 3.5 in the style of Walt Whitman. This poem was presented to a panel of nearly 700 people with no specialized knowledge of poetry, who were asked to choose between classic English poems and poems produced by AI in a matter of seconds.

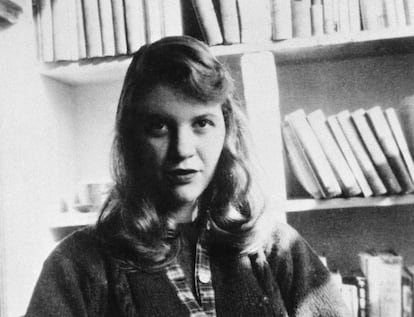

A new study, published in Scientific Reports, compares dozens of poems generated by ChatGPT to those written by classic English poets, from Chaucer and Shakespeare to T.S. Eliot, Sylvia Plath, Emily Dickinson, and Allen Ginsberg. The researchers conducted two experiments: one asked participants to determine whether a poem was written by a human or AI, and the other assessed the quality of the poems. In both cases, the AI-generated poems either passed as human-written or even outperformed their human counterparts. Notably, the researchers did not select the “best” poem written by ChatGPT, but rather chose the first result.

So, how did this happen? The simple answer is that poetry is inherently difficult to interpret, and the reading group preferred poems that were more accessible, which they mistakenly associated with human authorship.

“The results suggest that the average reader prefers poems that are easier to understand and that they can understand,” says Brian Porter, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh and co-author of the study. The panel seemed to interpret complex verses by poets like T.S. Eliot as “hallucinations,” dismissing them as impossible to have been written by humans. The five highest-rated poems were all generated by AI, while the lowest-rated poems were human-written.

“Some participants explained that the emotional content of a poem was a sign that it was written by a human,” explains Porter, although these poems were actually produced by ChatGPT. “Others seem to interpret confusing or difficult lines as AI errors, rather than intentional choices by a poet. The results suggest that people take liking a poem as a sign that it was written by a human, rather than an AI.”

The study’s focus, however, was not on people’s ability to distinguish between English-language classics and AI-generated poems, but on how well AI can mimic human writing. In this, AI succeeded: “The main takeaway from the experiment is that AI is capable of creating poems that convey emotions and ideas in a way that convincingly resembles human authorship,” Porter states.

And what would the experts do?

Would a group of critics, academics, or poetry experts have given more precise answers? A group of Spanish academics already asked this question. Collaborating with Argentine writer Patricio Pron, they competed with AI-generated stories and had them judged by a small panel of critics. The human writer won: “The difference between critics and casual readers is immense,” says Julio Gonzalo, a professor at Spain’s UNED university and author of this study.

“AI is easy to confuse non-experts,” says Guillermo Marco, a UNED researcher and poet, and co-author of the work with Pron. “We reach a conclusion that we may already have known, but it is very good to have measured it: a well-designed blockbuster with big data can have a better chance of success than something more risky,” Marco adds.

Working with Patricio Pron had the advantage of using new, original stories. The researchers acknowledge the challenge in conducting a similar study with experts on classic poems. “We suspect that a group of poetry experts could do it better, and we plan to try it soon, but that means finding classic poems that poetry experts do not immediately recognize, which is quite difficult,” says Porter.

Interestingly, when participants were informed that a poem was AI-generated, they automatically liked it less. This reaction may reflect human skepticism toward machine-generated art, a trend Porter doesn’t think will disappear anytime soon: “I’m not sure people will ever fully accept AI-generated poetry — or even AI-generated art in general. Language is often a tool for one person to communicate ideas to another, and AI, at its core, is just mimicking that.”

It's an aesthetic issue

In their latest article, Gonzalo and Marco show that machines don’t need extraordinary capabilities to outperform human judgment when evaluating creative texts. Even a small language model with 500 million parameters (compared to the 175 billion parameters of newer versions of ChatGPT) was enough to pass most of the criteria for a common reader with flying colors. “With these experiments, we delve into questions more related to sociology and aesthetics — about how taste is shaped by society or education,” Marco explains. “It’s difficult to judge art without sufficient prior experience,” he adds.

Marco is more blunt about the limits of AI’s ability to create artistic experiences: “Art is about communicating human experience. AI is a very, very powerful tool, but it will end up becoming like an autotune for creativity. It will never be autonomous nor have the need to express itself unless given instructions.”

This success of AI over human judgment has prompted the researchers to consider whether there should be regulation requiring clear warnings when content is generated by AI. “If readers value AI-generated texts less, and there is no warning that AI-generated text is being used, there’s a risk that people may be misled into paying for something they would not have accepted had they known it involved AI-generated text or art,” says Porter.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.