The obstacles still ahead on the road to normality: ‘The virus will not disappear so fast, if indeed it ever does’

While the number of contagions is expected to fall as the Covid-19 vaccination drive progresses, epidemiologists warn restrictions and face masks will still be needed to combat the pandemic

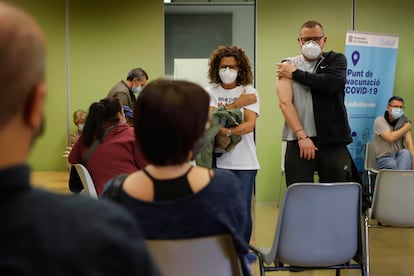

The progress of Spain’s Covid-19 vaccination campaign has sparked a wave of optimism in the country about the future of the pandemic. With a large part of the vulnerable population already inoculated and 14.9 million people (31.4% of the population) with at least one dose of a vaccine in their arms, the experts have no doubt that the main indicators of the epidemiological situation – the incidence rate, hospitalizations and deaths – will fall sharply in the coming months. But group immunity, they warn, will not be achieved this year and right now it is difficult to see whether the world will reach this stage given the threat of new variants and the lack of vaccines to administer to the global population in the medium term.

“The virus will not disappear so fast, if indeed it ever does,” warns Antoni Trill, the head of the Preventive Medicine service at the Clínic Hospital in Barcelona. “We will move toward normality, but there will still be infections,” he continues. “Instead of group immunity, we are talking in this case about a functional control of the pandemic. We are not going to be able to say goodbye to masks so quickly.”

A more transmissible virus forces you to vaccinate more people. Perhaps 80% to 90% will be needed now for herd immunityQuique Bassat, epidemiologist and researcher at the ISGlobal institute in Barcelona

Since the start of the pandemic, the oft-repeated mantra has been the claim that group immunity – also known as herd immunity, when the percentage of immunized people stops the virus from circulating thus protecting those who haven’t been inoculated – would be achieved once 70% of the population has received their doses. Spain’s prime minister, Pedro Sánchez, recently announced that a situation of group immunity is just “100 days away” thanks to the speed of the vaccination campaign.

The problem is that this 70% will not be sufficient due to the new variants of the virus that are appearing. Quique Bassat, epidemiologist and researcher at the ISGlobal institute in Barcelona, explains that “the percentage of people who need to be vaccinated depends on the basic reproductive number of each virus, the R number.” This figure indicates how many new cases on average will be caused by one infected person.

“A year ago, the estimate for the SARS-CoV-2 R number was 2 to 3, and that is where the objective of 70% came from,” Bassat continues. “But now there are more contagious variants and the R number could be between 3 and 5. A more transmissible virus forces you to vaccinate more people. Perhaps 80% to 90% will be needed now.” Measles, which is even more contagious with an R number above 12, requires more than 95% of the population to be vaccinated in order to achieve group immunity.

More time will be needed to vaccinate more of the population, and this will have an effect on the speed with which Spain is heading towards life without restrictions or masks. “This will be a slower and more progressive process, one that cannot be done from one day to the next,” admits Clara Prats, a researcher in Computational Biology at Catalonia’s Polytechnic University, which is developing a model that will predict the speed at which this could happen under a series of different scenarios.

In Spain, a country that is well known internationally for its adherence to vaccination programs, it is not unreasonable to predict that very high percentages of immunity can be achieved. But in the United States – which, paradoxically, is the large country where vaccination got going the fastest – there is growing concern over the reticence of some sectors of the population to get vaccinated. This has led several experts to recently express their doubts to The New York Times as to whether herd immunity will actually be achievable in that country.

Whatever the case, the experts agree that “the important thing now is to move forward and vaccinate as many people as possible.” Even without reaching herd immunity, they explain, the impact of the illness could be reduced to the minimum and the return to normality will be almost complete. “This is not an all-or-nothing situation,” explains Trilla. “With the measles, we haven’t managed to avoid there being cases and we live with it with hardly any problems.”

Santiago Moreno, the head of infectious diseases at the Ramón y Cajal Hospital, believes that it “will be possible to corner the virus in a way that it will be reduced to a minimum expression, with few cases and nearly all of them mild, while not actually making it disappear.”

In the race between vaccines and variants, the vaccines will winFederico García, head of the microbiology service at Granadas San Cecilio Hospital.

Bassat predicts two scenarios. “In the medium term, with between 50% and 80% of the population vaccinated, we will have a few hundred cases every day and a fall in hospitalizations and deaths. In this phase, albeit in a more relaxed way, it will still be necessary to maintain some prevention measures.” In the longer term, he believes, “there will be localized outbreaks with relatively small clinical importance. The most vulnerable collectives will be protected and it will be possible to locate and isolate all of those affected, tracing contacts, vaccinating and re-vaccinating…” he adds. Once this point is reached, normality will be very close.

The experts have declined to offer a concrete date as to when this moment will arrive, although they suggest it could be around the end of this year or the first half of 2022. They do agree that the use of masks in open spaces without crowds, a measure that is being questioned more and more in Spain, will not be around for much longer. “The key will be in enclosed spaces with a lot of people from different origins,” Bassat explains. “Masks will have to be worn there and vaccine certificates will be important.”

One of the key moments for the deescalation of measures will be in schools, with an end to the “bubble” groups of students and mask-wearing among children. According to the epidemiological situation, this could happen around the end of this year or the start of 2022 at the latest. The first proposal from the Spanish government sent to the regions suggested that both measures would be kept in place at the start of the next academic year.

Bassat explains the reasons behind this thinking. “In September, adolescents aged 12 to 16 will not be vaccinated and the virus will circulate among them. They will be practically the last group for which this poses a risk, given that it will happen with an R number of around 1. So the logical next step is to vaccinate them. The United States has already approved this and it is likely that Europe will do so in June.”

What is not yet so clear is vaccination among primary school children, those aged six to 12. This group does not easily pass on the virus, with an R number of around 0.3, and sufferers have few clinical symptoms from Covid-19. As such, the risk-benefit factor is doubtful. “But they should continue to wear masks to minimize the circulation of the virus until adolescents are vaccinated. But when this happens, that is when masks should disappear from the classrooms.”

The experts warn, however, that these reasonable epidemiological criteria, when applied to a country like Spain, can change once the focus is widened. The key issue is whether it will be enough to vaccinate ever-younger people who are not at great risk in rich countries, while in developing nations not even the most vulnerable have received a single dose.

The director of the World Health Organization (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, on Friday called for wealthy countries to rethink their vaccination strategies. “In poor countries, there aren’t enough vaccines to even vaccinate healthcare workers,” he complained.

The leader of the WHO is calling for vaccines to be donated to the most-needy countries instead of going to adolescents for now. “On a global scale, there has been a lack of solidarity,” opines epidemiologist Pedro Alonso, who runs the WHO’s program combating malaria. “All of us talk about it, but we rush to vaccinate our populations first. And that is a complex issue, because it is difficult to reproach governments for doing so.”

We have to get as close as possible to global group immunity. Doing so quickly is the only way to minimize the impact of the virus and the risk of the new variantsAntoni Trill, head of the Preventive Medicine service at the Clínic Hospital in Barcelona

No one is safe until the whole world is safe. This is the phrase that is being used to warn the world that until global herd immunity is close – albeit not fully achieved – not only will there be tough moral decisions ahead, but also “a greater risk of more contagious variants that could affect Spain and the other countries that are already vaccinated,” warns Federico García, the head of the microbiology service at Granadas San Cecilio Hospital.

The fear is not so much a super-variant that is immune to all existing vaccines, explains García. “I don’t think there will be time for something like this to happen,” he says. “And even if it did, we have learned a lot and we have the technology to rapidly adapt existing vaccines and finish developing others. In the race between vaccines and variants, the vaccines will win,” he adds.

The objective, the experts agree, is to shorten this race as much as possible in order to reduce the enormous global cost of the pandemic. Humanity still doesn’t know whether it will manage to eliminate the virus or if it will have to learn to live with it – if Covid-19 ends up becoming a seasonal illness or the cause of ever-smaller outbreaks that will no longer be newsworthy. “What we do know is that we have to get as close as possible to global group immunity,” Trilla concludes. “Doing so quickly is the only way to minimize the impact of the virus and the risk of the new variants. This is the objective that the whole world has before them in the coming months.”

English version by Simon Hunter.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.