The 24 DNA letters linked to autism: GCAAGGACATATGGGCGAAGGAGA

A team of Spanish scientists has discovered the mechanism that could explain a high percentage of autism spectrum disorders

Around one in 100 people live with an autism spectrum disorder, a developmental brain disorder characterized by difficulties in social interaction and unusual behavior patterns, such as an acute attention to detail. In only one in five cases is a significant genetic mutation detected. However, an international team of scientists, proposed a possible explanation for the remaining 80% of cases on Wednesday: the loss of a tiny segment of a protein essential for brain development. The genetic code for this fragment consists of just 24 chemical letters: GCAAGGACATATGGGCGAAGGAGA. The researchers — led by biochemist Raúl Méndez, 59, and biophysicist Xavier Salvatella, 52 —believe that these 24 letters could be key to reversing autism.

To understand this breakthrough, we must go back to the very beginning: the fertilized egg. This single cell contains a kind of instruction manual, DNA, made up of around 3 billion letters. Each letter represents the initial of a chemical compound — G, for example, stands for guanine (C₅H₅N₅O). This solitary cell will divide and multiply, eventually forming a person composed of about 30 trillion cells, each distinct despite sharing the same DNA — whether it’s a neuron in the brain, a myocyte in the muscles, or a melanocyte in the skin.

The key to this diversity lies in the fact that DNA functions like a piano, with each cell playing a different tune. In neurons, the CPEB4 protein acts as a conductor, regulating hundreds of genes essential for brain development. In 2018, Spanish researchers found that people with autism were missing a segment of this protein, linked to the 24 DNA letters. Their new study, published on Wednesday in Nature, reveals how the absence of this segment leads to the deregulation of 200 genes associated with autism spectrum disorders.

Biochemist Raúl Méndez, from the biomedical research institute IRB Barcelona, is an expert on CPEB4. “It is a protein that is synthesized and regulated in response to various types of stress,” explained the scientist during a press conference organized by Science Media Center Spain. “Our working hypothesis, which we have not yet proven 100%, is that during embryonic development some type of stress occurs that triggers this process of loss” of this crucial segment, explained Méndez. The Madrid-born biochemist points to possible causes, such as a chronic diet high in fat or a viral infection.

Fringe anti-vaccination movements have been linking autism to vaccines since 1998, when the discredited British doctor Andrew Wakefield published a fraudulent study that blamed the MMR vaccine for autism spectrum disorders. His conclusions, based on falsified data, have been debunked countless times. For instance, a study involving more than 500,000 children in Denmark found that autism rates were the same among vaccinated and unvaccinated children. “We do not want any anti-vaxxer to use our working hypothesis to question the effectiveness of vaccines,” Méndez emphasizes in a video conference with EL PAÍS.

Cells use a code to read the 3 trillion letters of human DNA. Every set of three letters is the recipe for an amino acid, the building blocks of proteins, which are the tiny machines that perform most of the tasks in the human body. Méndez and Salvatella’s goal is to test, first in mice genetically modified to simulate autism, whether administering the eight amino acids encoded in the sequence GCAAGGACATATGGGCGAAGGAGA can reverse the disorder.

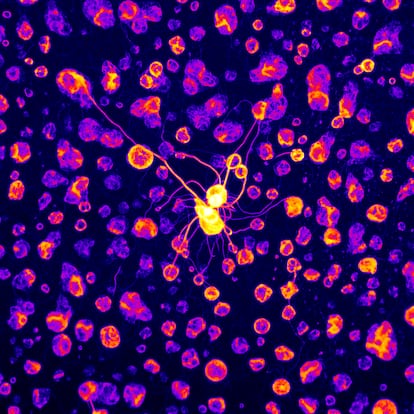

“We didn’t have a molecular description of what the eight amino acids missing in autism do,” says Salvatella, a 52-year-old researcher from Barcelona who also works at IRB Barcelona. The biophysicist explains that CPEB4 proteins tend to aggregate by the hundreds and form “liquid droplets” inside neurons. When there is neuronal stimulation, the droplets break up and release their contents. However, when those eight amino acids are missing in a large number of CPEB4 proteins, “those droplets basically become solids” that don’t function properly, triggering the deregulation of the 200 genes associated with autism.

The new research is part of the doctoral theses of Carla García Cabau and biophysicist Anna Bartomeu. “Now we need to find a way to reverse these effects, making the droplets liquid again,” as they are when the CPEB4 protein is complete, says Cabau, a 30-year-old researcher from Barcelona. The authors have observed that simply adding the eight missing amino acids is enough to restore the function of the droplets in experiments with purified proteins in the laboratory — a very preliminary but hopeful result.

The researchers are confident that the sequence GCAAGGACATATGGGCGAAGGAGA holds the key. “In the 2018 study, we saw that when these eight amino acids are missing, autism develops and the neuron doesn’t function properly, but we didn’t know why. Now, we understand the role of these eight amino acids in this protein,” explains Méndez, who led the work six years ago along with José Javier Lucas and Alberto Parras, from the Centre for Molecular Biology Severo Ochoa (CSIC-UAM) in Madrid. The biochemist is optimistic, even about the possibility of reversing autism’s effects in adults in the future. “In principle, there would be enough neuronal plasticity. In fact, when someone suffers a stroke, the rest of the brain often adapts to recover functions lost in the brain area that has died. More plasticity than that is impossible,” he argues.

The biologist Ana Kostic praises the new research, in which she was not involved. “The study is highly relevant as it elucidates molecular underpinnings of autism spectrum disorder and identifies potential therapeutic approaches,” says Kostic, Director of Drug Discovery and Development at the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment in New York. “One can imagine that manipulating a 24-nucleotide fragment may lead to an improvement in the symptoms associated with idiopathic autism spectrum disorder; however, this hypothesis will need to be validated in preclinical models (as suggested by the authors) and then tested in clinical trials. It is difficult to predict the degree of benefit in different age groups, but it is possible that this approach would lead to an improvement even in adult individuals with autism spectrum disorder,” Kostic notes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.