A guide for aliens: how to interpret the messages sent from Earth in the Pioneer and Voyager space probes

Four planetary probes were launched in the 1970s, carrying information about Earth. This was in case – in the very distant future – they were to fall into the hands of an extraterrestrial civilization

NASA has just re-established contact with the Voyager 2 probe, after two weeks of silence. Launched in 1977, it carries a message for aliens – something that has received a lot of attention in recent days, after statements by a whistleblower in the US Congress assured the public that the Pentagon is hiding “non-human remains” of extraterrestrial origin.

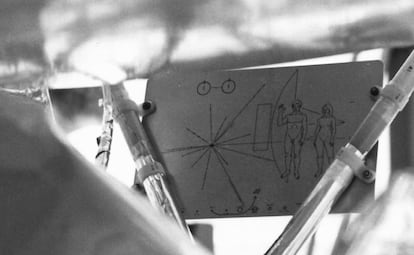

In the 1970s, a total of four planetary probes were launched, each of which carries messages in case they fall into the hands of an extraterrestrial civilization in the very distant future. This idea was the brainchild of Eric Burgess – a British consultant – who suggested it to Carl Sagan and Frank Drake of the Planetary Society. The two astrophysicists created the basic design of the first postcard that we sent to our alien neighbors, explaining who we are and what we do. The initial messages consisted of two identical plaques attached to the sides of the Pioneer 10 and 11 probes. These were directed towards Jupiter… although Pioneer 11 also visited Saturn after a cosmic detour. Those two spaceships were the first to reach the speed necessary to escape the Sun and enter interplanetary space.

For us, the meaning of some elements of the plaques are obvious. The two human figures, for example: based – very loosely – on Greek sculptures and designs, they were heavily criticized in their day. Multiracial traits were included in the figures, although a department at NASA imposed censorship, after considering the depiction of the female character to be too explicit. While an extraterrestrial would hardly be able to interpret the friendly gesture of the raised hand, the salutation was ultimately left intact, because at least it allowed all five fingers to be exposed (with the opposable thumb).

The most important references are the two circles in the upper left corner of one of the plaques. They represent a hydrogen atom in its two states: with the electron in its upper and lower energy levels. When this leap occurs, the atom emits a characteristic radiation that’s eight inches in wavelength – the most abundant in the universe. The scientists thought that an alien should know about this. Between the two atoms, a vertical line indicates a binary “one.”

To the right of the woman, two lines indicate her real-life height: 5 ft 8 inches. The man is a little taller. Behind them is a profile of the Pioneer, drawn to scale. In the lower margin, the Solar System is visible (including Pluto, which was still considered to be a planet in the 1970s). The trajectory followed by the ship is indicated, highlighting the gravity assist maneuver which was utilized when passing Jupiter – the planet that gave it the escape velocity. Its antenna points towards a third little circle: Earth.

Next to each planet, a unit of scale offers the distance from the sun. The unit of scale here isn’t that of radiation from hydrogen, but one-tenth the distance from Mercury. Above it appears the binary 1010, or 10. Pluto is 1111111100 times further away. If the aliens are able to crack this complex code, they’re undoubtedly very intelligent.

And where are we? The key is given by the dashed star to the left of the two human figures. The longer horizontal line conveys the distance from the Sun to the center of the galaxy. The other 14 lines show the directions of pulsars: cosmic lighthouses, characterized by their regular and rapid flashes. The long binary numbers indicate the distance (again, taking the hydrogen transition as the unit). Since the plaque was flat, the third dimension is given by the length of the line, proportional to the height of the pulsar above the galactic plane. With this information, any alien could triangulate and deduce the location of the Sun among the millions of stars in the Milky Way. A simple task, no doubt… or, at least, so its authors believed.

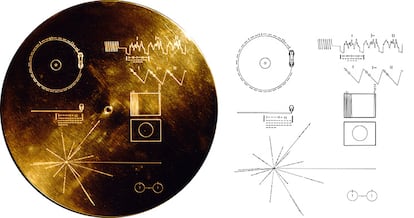

A few years after the Pioneers were launched, the two Voyager probes carried a much more sophisticated message on board: a vinyl-like record, inside a time capsule with the necessary equipment to play it. Like the plaques, it was covered by a thin layer of gold, meant to protect it during an eons-long journey.

The disc contains photos and sounds: images of the Earth – both from orbit and landscapes – and of flora and fauna. There are human anatomy charts, world maps showing the continental drift, the Sydney Opera House and the Golden Gate Bridge (duly annotated in binary, to indicate longitude), belly dancers, the UN building (by day and illuminated at night), the Taj Mahal, a supermarket, a finish line for the 100-meter dash, Jane Goodall with her chimpanzees, a page from Newton’s Principia and the score of a cavatina by Beethoven.

There were 116 images in all. One of them (#78) – which showed a diver and a fish – was ultimately unpublished, due to a failure to reach an agreement with the author on the copyright issue. In its own way, this absence also provides interesting reflections about our society.

The audio section is made up of greetings in 50 languages, from ancient Sumerian (which only a couple of hundred academics speak) to Mandarin – the most-spoken language in China – or Telugu, typical of central India. Unfortunately, there was no Swahili: the announcer who was supposed to participate forgot about the appointment and didn’t show up at the recording session.

Other more subtle recordings may pose interpretation difficulties for an alien: a volcano eruption, crickets and frogs, Morse code beeps, the striking of two flint stones, a ship’s siren, the soft sound of a kiss… or the hum of an electroencephalogram. Perhaps, it was thought, a sufficiently advanced civilization would be able to interpret it and read our thoughts.

There was also a music section, including three pieces by Bach (there were those who proposed including his complete work, but the idea was discarded because “it would have been showing off”); orchestral samples from Java, pygmy coming-of-age songs, mariachis, blues compositions by Louis Armstrong and Chuck Berry’s Johnny B. Goode. Mozart’s Queen of the Night and the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 came together with Navajo songs, Peruvian flutes and a fragment of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Here Comes the Sun by the Beatles should have been included, but the record company that owned the rights denied NASA authorization.

Instructions on how to play the record are engraved on its surface: like on the plaques, they show the scale based on the transitions of the hydrogen atom and the pulsar map. There’s also a view of the disk in plan and profile. In binary, the speed (3.6 seconds per lap, or 16 rpm) and a sample of the signals that the records have to generate – as well as the duration of each image (8 milliseconds) – are noted. Finally, two rectangles present a schematic of the electronic scan on the screen (to be provided by the aliens). If all goes well, the first calibration image will appear: a perfect circle.

Voyager 1 will pass close to the star Gliese 445 in 44,000 years; its twin, a couple of light years from Ross 248, will pass by in 33,000 years. If no one picks them up there, they’ll continue on their journey. Statistics suggest that, every 50,000 years, they should approach one or another star before getting lost in the Milky Way.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.