Victims of the Madrid triple murderer released by Trump speak out: ‘We cannot understand the silence of the authorities’

Devastated by the news that the killer was freed in a prisoner exchange with Venezuela, the families of the three victims have received no information from the Spanish government

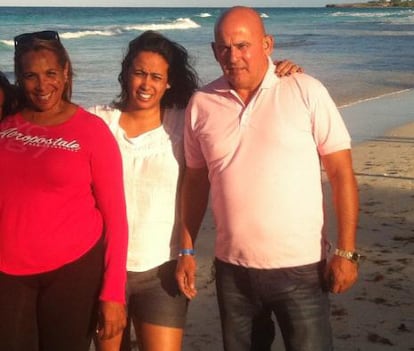

The first thing Yaimara Osorio does after sitting down to speak with this newspaper is clarify that in the nine years since her mother was murdered, she has never given an interview. She takes a sip of her coffee, sighs, and begins her account, trying not to break down.

Yaimara explains that until now, she wasn’t in the right frame of mind to speak to the press, nor did she feel like doing so, despite the media interest sparked by the horrific 2016 crime in which a former U.S. Marine killed three people at a law office in Madrid. But now she feels strong enough, and she has something to denounce. The killer, Dahud Hanid Ortiz, of dual American and Venezuelan citizenship, has been released in the United States after serving just six years and nine months behind bars, thanks to his surprising inclusion on July 18 in a prisoner swap — which sent home more than 200 Venezuelan migrants who were being held in a maximum security prison in El Salvador — between the U.S. and Venezuela, where he had been serving a 30-year sentence. The families of the three victims are devastated, but the Spanish authorities have ignored their pain.

“They haven’t even bothered to call us,” says Yaimara. “I know they might say there’s little they can do, that the matter has moved to another jurisdiction, but what we cannot understand is the silence.”

The families found out about the murderer’s release on Monday the 21st, shortly before it hit the press. They received a phone call from the owner of the law firm, Víctor Salas — the man the killer had targeted in a jealous rage after discovering he had a romantic relationship with his wife, Irina Treppel. That weekend, the German police had informed Irina, who lives in Germany, and she called Víctor. Outraged, the lawyer felt he had to speak to the media, but first, he informed the victims’ families.

“I have very bad news to give you,” he told Yaimara. She thought it might be something related to the compensation they’re still waiting for as victims of a violent crime. What Víctor told her hadn’t even crossed her mind: “The killer has been released as a political prisoner.”

Yaimara had a very close relationship with her mother, Maritza Osorio Riverón, who was 51 at the time. “We were like friends, she was my party buddy,” she says. She recalls the horror of that day nine years ago: getting the news from a cousin, rushing to the lawyer’s office, crossing the police tape, and seeing the bodies on the sidewalk, covered with sheets. “The worst part was that they made me identify the body. That image will never leave me.”

Now, during this interview at a café in Madrid, she asks for one message to be made clear: “How is it possible that no one has told us anything about something so serious — so serious that even the police detectives told us they had never seen a crime like this?”

Nor have there been sufficient explanations given to the press. The case is surrounded by a strange silence from both U.S. and Spanish authorities. The responses to the media have been sparse, limited to written statements with no attribution to any senior official.

The U.S. State Department said they had taken the opportunity to bring home all American citizens “detained” in Venezuela, many of whom had reported torture and other forms of mistreatment. Dahud was repatriated along with nine other released individuals, who were political prisoners, according to activist groups that monitor such cases. “Out of respect for privacy, we will not go into the details of any specific case,” the Trump administration said.

Spain’s Ministry of Justice stated that it had ceded jurisdiction to Venezuela, where Dahud was arrested two years after the crime. This was because Caracas refused to extradite him, arguing that he was a Venezuelan national by origin. Sources within the Spanish Prosecutor’s Office told this newspaper that there is no available judicial remedy. However, last Thursday it emerged that the Spanish public prosecutor had sent U.S. authorities a report outlining the killer’s legal situation.

Meanwhile, one of the top figures in the Chávez regime in Venezuela, Diosdado Cabello, publicly celebrated that the U.S. had taken in a murderer and claimed that American negotiators had insisted on including Dahud among the freed prisoners.

The New York Times revealed this Friday that, according to internal emails, officials at the State Department debated how to explain to the American public that they were repatriating a criminal as part of a group of political prisoners. That inclusion appeared to undermine president Donald Trump’s usual rhetoric about keeping criminals out of the country.

In a statement to the paper, the department in charge of foreign relations said: “We are very pleased that nine innocent, wrongfully detained Americans have been freed from Venezuela. The Trump Administration is committed to law and order; violators will be held accountable for their crimes.” The Times also reported that, according to two sources familiar with the case, Dahud remains free. As of early Saturday, EL PAÍS had not received a response from the State Department clarifying the Trump administration’s plans.

Meeting with Peinado

The families have made repeated efforts to obtain information from the authorities. They have gone twice to the office of Judge Juan Carlos Peinado, who handled the case in Spain, located in Plaza de Castilla, seeking answers. Officials informed them that the judge was on vacation, but they managed to secure an appointment for next Monday at 10.00 am. They don’t know if he will offer them any hope.

The three victims of the June 22, 2016 crime were all of foreign origin and modest means. Maritza, Yaimara’s mother, was Cuban. Although she was entitled to Spanish citizenship, she had never applied for it, fearing the communist regime would seize a property the family still owned on the island. She had been working for years as a secretary at Víctor Salas’s law firm, located at 40 Marcelo Usera Street — a busy thoroughfare in the working-class heart of southwest Madrid.

The second employee who was killed was attorney Elisa Consuegra Gálvez, a 31-year-old Cuban who had been living in Spain for four years and helped with the firm’s paperwork. Just weeks before the murder, she had finally managed to validate her law degree in Spain.

The client murdered was Pepe Castillo Vega, a 42-year-old Ecuadorian who had acquired Spanish citizenship. He had left his taxi double-parked with the hazard lights on to quickly pick up some documents for his wife’s permanent residency renewal. Just minutes before entering the office, he had said goodbye to her — they had been together for eight years. The killer mistook him for the attorney, the man he had come to kill.

Pepe’s widow speaks to EL PAÍS over a video call. It is also her first interview, and she agrees to it only under the condition that her name not be published. She asked a trusted person to watch over their 11-year-old son at a different home, so he wouldn’t overhear the conversation. The boy, who has a disability, has suffered deeply from his father’s absence, and his mother has had to remove all the photos of him from the house.

In tears, she says that since learning of the release, she has been plagued by nightmares and panic attacks. She’s requested the Madrid City Council install a security camera in her home. Due to their vulnerability, they are the only victims who have received an advance on public aid for victims of violent crimes, according to attorney Víctor Salas. To apply for this benefit, a final court ruling is required, which only came in May of this year, when the Venezuelan Supreme Court denied Hanid Ortiz’s final appeal against his conviction for the crime in Spain.

During the two years the killer was on the run, she lived in constant anguish — an anguish that was only eased when he was sentenced. “It gave me peace,” she says. “They weren’t going to bring Pepe back, but at least his killer was where he belonged.”

Two weeks ago, when Víctor told her what had happened, her world collapsed. “Everything I had already worked through came rushing back. It’s happening all over again,” she says.

But this time, it feels different. Back then, in those first days of shock, they felt the support of the police and interest from the media. Now, the killer’s release seems to be surrounded by an eerie sense of normalcy, as if it were just a passing story. “That’s what’s so strange,” she says, referring to the apparent indifference of the Spanish authorities. “It’s like they just wash their hands of it and stay silent. No one calls us. No one…”

The father of the youngest victim, Elisa, is Juan Carlos Consuegra, 69. He works as a night security guard for a residential building in Madrid. The pain of losing “the girl,” as he calls her, was so deep that her mother, he says, “stopped existing.” Elisa, a forensic doctor and professor at the University of Medical Sciences in Havana, passed away in 2021. She was 64 years old.

Juan Carlos questions the apparent inaction of the Spanish state, which he believes reflects poorly on the country. “People might think someone can just come here, kill three people, and walk away. What good are Spain’s laws, then?”

“If it weren’t for the press, no one would even know about this,” he adds. “No one says a word. Total silence. Over there, over here, everywhere.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.