The strange end of Mexico’s Iztacalco serial killer erases the trail of more dead women

The chemist Miguel Cortés died in solitary confinement in his prison cell without a sentence, ahead of a series of trials for murder. Authorities talk about a fall, an intoxication and cardiac arrest. The families of the victims blame the Prosecutor’s Office for inaction and irregularities in his death

It was a simple and ridiculous fall while he was sleeping, according to the initial report. A police document from last Sunday reported the demise of Miguel Cortés, the alleged serial killer of Iztacalco, who died without any sentencing and before the start of the first of the many trials that awaited him. In the early hours of that day, he was taken to the hospital. Doctors ruled his death was caused by an “intoxication that led to cardiac arrest.”

They did not specify what the substance was, how it got to his isolation cell, or whether the fall had anything to do with it. Cortés had been in prison for barely a year after being arrested on April 16 of last year, when the mother of his latest victim, a girl who lived in his building, found him abusing her. The girl died of asphyxiation, her mother was stabbed several times, but he was unable to escape. Officers found women’s bones in his apartment, identification cards of people who had been missing for years, diaries detailing the crimes and the blood. The evidence pointed to a lifetime of murder with impunity.

Cortés led a low-profile life in the blue-tiled building on 16 de Septiembre Street in Iztacalco. He went to work in a laboratory, didn’t speak to the neighbors, and wasn’t often seen with people. Born on October 5, 1984 in Mexico City, he was a tall, powerful man. On social media he championed a vegan lifestyle, opposed bullfighting, and advocated for animal rights. He attended animal rights protests and posted photographs of himself in his white lab coat. Occasionally, he wrote dark poems on his profile, alluding to cold bodies and anonymous women. There’s a photo of him with his arm around a young woman who stares seriously into the camera lens. Frida Sofía Lima Rivera made some comments on some of those photographs. That year, the 22-year-old student disappeared.

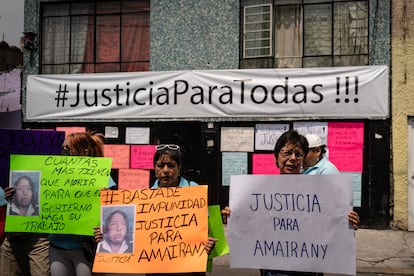

Residents in the neighborhood remember seeing her. She was talkative and told them about her life in a rural town in Morelos, where she was from. When she disappeared, everyone thought she had simply returned to live with her parents. When Miguel Cortés was arrested, Frida’s mother spoke on television and said that her daughter had a relationship with the suspect, that she referred to him as “father,” and that he had given her the book Perfume, a famous novel about a serial killer of women. The investigation into Frida’s whereabouts stalled after years of lack of evidence and errors in her file, such as her age. DNA tests were supposed to confirm whether some of the bones in Cortés’ apartment belonged to her. Cecilia González, the mother of Amairany, who disappeared 12 years ago when she was 18 and had gone out to collect some photos for her graduation document, had the same hope. Cortés was listed in her investigation file as the last witness to see her that day.

The day that Cortés’ prison warden asked the medical services to transfer him to the hospital due to the fall, the detainee was scheduled to attend a hearing to link him to two other cases involving potential victims. The families were notified at 12:00 noon on April 13 that the appointment was canceled due to Cortés’s medical emergency. At 6:00 p.m., the Mexico City Attorney General’s Office informed them of the death of the sole suspect in the killings of so many women, including Viviana Elizabeth Garrido Ibarra. The 32-year-old disappeared on November 30, 2018, and was a chemical engineer, just like Karen Ornellas Baltazar, who disappeared the day after her 21st birthday. A friend of Baltazar told the media that the young woman’s birthday party took place at Cortés’ apartment, and that he walked her to the subway afterward. Her body was eventually found with signs of asphyxiation. The unsolved cases of both women had the chemist as the prime suspect, but no action had been taken.

Erendali Trujillo, the lawyer for his last victims, María José and her mother Cassandra, was one of the only visitors that Cortés received in prison. She arrived with a team of experts to prepare a psychological profile of the alleged murderer. She sought to document his dangerousness in order to request the maximum sentence, 116 years, and to have him transferred to a maximum-security prison where he would be more closely monitored. From the interviews with Cortés, Trujillo recalls his calm, respectful tone, and his formal use of the Spanish “usted” (the polite form of “you”). “You could tell he had a career,” she notes. He admired famous serial killers who had made it onto television, such as Dahmer and Bundy. In fact, the lawyer points out that his apartment was decorated in the style of “The Milwaukee Butcher,” the nickname of the young man who killed 17 children in crimes involving sex and cannibalism in the United States.

The psychological profile determined that Cortés was a dangerous and narcissistic person, and that he was a risk around other inmates. Because of this, he lived in a restricted area of the Eastern Prison, with just a few inmates who considered him arrogant. The police indicated in the report that Cortés was taking medication, and the lawyer adds that his physical appearance had deteriorated. “He smelled unpleasant, with a very peculiar pH. He wore plastic sandals. He entered the prison weighing 90 kilos (198 lb) and was thin in interviews, down to about 70 kilos (154 lb),” she recalls.

No one had visited him during that entire year in prison, neither his sister nor his mother. In fact, he had asked them to stop spending money on lawyers because “he knew he was going to stay in there.” The only thing he asked the lawyer for in exchange for talking was a book, Manual del asesino en serie: Aspectos criminológicos (The Serial Killer’s Handbook: Criminological Aspects), by Juan Francisco Alcaraz Albertos. In return, he confessed off camera that he had murdered more than 30 women, some in Mexico and others in other countries. “You have to believe only half of what he says because these guys tend to brag a lot. He wanted to be famous and wondered why he wasn’t being sent letters to prison like the murderers he admired,” Trujillo explains.

Now that Cortés is dead, María José’s case will be dismissed, Trujillo notes. Cassandra took advantage of the mass marking the first anniversary of her daughter’s death to insist that she doesn’t consider that justice has been done now that the suspect is dead. Her neck covered in scars from the one-on-one confrontation with him when she saw him over the teenager’s half-naked body, she recalled the mocking call her family received from Cortés in prison. Fernanda, María José’s sister, wonders how the detainee accessed her private number and called her three days before he died. He told her he was sad about what he had done, that he couldn’t believe a year had already passed. She yelled at him on the phone that he was a murderer, and he responded with a laugh. “He told me yes, he might be a murderer, but that he didn’t regret anything he had done to my sister and the other women,” she recalls.

Cortés died without a trial or sentence, leaving the families of his victims without a sense of justice. Now, Trujillo’s legal team seeks to certify the veracity of the chemist’s death, uncover the circumstances that led to his death in solitary confinement and under watch, and to sue the Prosecutor’s Office for failing to act. No investigation ever cross-referenced the information in the three files in which Miguel Cortés’ name was mentioned as a suspect or witness in the disappearance of women since 2012. “At least if Miguel Cortés had died with a sentence, so that the real victims attributable to him had been identified... Now we will never know. If he murdered more women, he took his secret to the grave,” Trujillo concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.