Spain: where who you know still matters more than what you know?

Inequality is growing in Spanish society, with an outdated education system and nepotism fuelling the differences.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s study of social mobility The Great Gatsby begins: “In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I've been turning over in my mind ever since. Whenever you feel like criticizing anyone, he told me, just remember that all the people in this world haven't had the advantages that you've had.'

It’s advice that many politicians would do well to keep it in mind as they turn their attention to Spain’s growing lack of social mobility.

And while they’re at it, they might ask themselves whether Spain offers equal opportunities, whether most of today’s younger generation will be better or worse off than their parents? And, most importantly, are the best people running the show?

There’s not a great deal of research around to help answer these questions, which is telling in itself. But what we do know is that if there were any hope for social mobility during the boom years of the last three decades, the crisis crushed it. As Olga Cantó. An economics lecturer at the University of Alcalá de Henares, points out, “People have been losing income since 2006; it’s going down rather than up.”

If there were any hope for social mobility during the boom years of the last three decades, the crisis crushed it

A closer look at Spain’s record on social mobility reveals that there has, in fact, been no change since the 1990s. “It’s extraordinary how relative inequality – the probability of moving up in the world – hasn’t altered,” says Ildefonso Marqués, a sociologist at Seville University and author of a study on social mobility in Spain that argues three decades has done nothing to improve the chances of a construction worker’s son or daughter becoming a doctor.

Cantó, however, maintains that Spain is not so different from its counterparts and is on a par with France and Germany, while doing better than Italy, the United States and Britain. But it still has a long way to catch up with Scandinavia, where background appears to be more or less irrelevant in terms of moving up the social ladder.

But another study by Spanish sociologists Carlos J. Gil Hernández, Pablo Gracia and Carlos Delclós argues that Spain lags behind France and Germany due to its policies on wealth distribution. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCDE) confirms that Spain is at the bottom of the league in this respect.

In which case, how should Spain fight inequality? The most effective weapon is a first-rate state education, beginning with nurseries. “For some low-income parents who don’t have much education themselves, a good nursery education will be more beneficial for their children than it will be for more privileged kids,” says Pablo Gracia. “Not only does it make up for what they might be missing at home, but it allows the mother to keep working.”

It is increasingly common – outside of Spain – to study the advantages that come from growing up in a well-educated family, reflected in the type of conversation that might take place around the table, along with museum visits, travel and help with school work.

It is increasingly common – outside of Spain – to study the advantages that come from growing up in a well-educated family

According to Cantó, the type of school – whether state, partially state-funded or private – has a greater effect on children in Spain than elsewhere in Europe. “The middle classes are deserting public education,” she says. Apparently, even atheists are prepared to accept the subsidized religious education on offer in state-funded Catholic Church run schools rather than put their children through state schools.

“Broadening the education offer has done nothing to reduce inequality,” says Carlos J. Gil. “Fifty percent of children with parents working in the professions go to university. Among the working class this figure drops to 15%.”

Inequality among students is perpetuated by the fact that only those able to pay for a Master’s degree, to go abroad or who have friends in high places, tend to find jobs.

Some studies even suggest that the outcome of a job interview can be influenced by class indicators such as the state of a candidate’s teeth, his or her accent and use of language, how they dress and what sports they play.

Few people would disagree that members of the upper echelons of all societies tend to help each other out. No need to look further than the Deloitte España scandal leaked earlier this year which showed that the auditor had a list of 117 job candidates who had been recommended by those holding top positions in the company.

According to Ildefonso Marqués, Spain’s obsession with education doesn’t help: this is a country of highly qualified waiters. “Germany avoided this scenario by limiting the number of university students, which has remained more or less constant since 1950,” says Marqués.

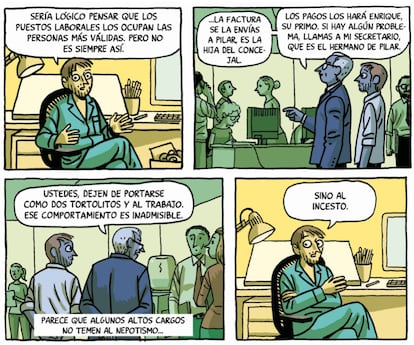

Nepotism and social injustice

Sociologist Luis Garrido insists that Spain’s education system needs a roots and branches overhaul. “Some 55% of Spanish girls and 35% of Spanish boys go to university,” he says. “But only 18% of jobs require graduates. It doesn’t make sense. And the universities make sure they all get through, so there’s no selection at that point. That comes later with nepotism and social injustice.”

“Passing everyone whether they deserve it or not, is an unfair system,” adds Garrido. “If you have a more demanding kind of university, then that would mean those leaving with degrees would find work. But we’re moving in the opposite direction. Having a degree has lost its significance.”

According to 2009 data from the Center for Sociological Research (CIS), 60% of young people who found work did so through personal contacts.

Meanwhile, Juan Pedro Velázquez-Gaztelu, author of a study of how Spanish capitalism works in practice, highlights the fact that only one state-funded Spanish university features among the 200 best universities in the world, though there are three private business schools on the list.

All of this, of course, has a negative knock-on effect on Spanish politics, says Garrido. “We have an increasingly poor caliber of politician,” he says. “The political parties, require you to toe the line, while the salaries are pathetic.”

At the end of The Great Gatsby, the narrator observes, “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” The author was referring to US society in the 1920s, but he could just as easily have been referring to Spain almost a century later.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Sign up for our newsletter

EL PAÍS English Edition has launched a weekly newsletter. Sign up today to receive a selection of our best stories in your inbox every Saturday morning. For full details about how to subscribe, click here.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.