Alison Bechdel, cartoonist: ‘We’ve gotten so polarized in the United States that we’re unable to see each other’s humanity’

The author of ‘Fun Home’ has published a satire in which a group of Boomers confronts the traps of capitalism and the contradictions of always being on the side of the good guys

Alison Bechdel has written a graphic novel about a character called Alison Bechdel. Both are famous cartoonists, live in Vermont with their partner, an artist named Holly, and had phenomenal success with their autobiographical work about their father’s homosexuality — a success they are still processing.

In the case of the real-life Bechdel, her graphic novel Fun Home was adapted for Broadway and won five Tony awards. The fictitious Bechdel is tormented by the televised version of her great work, and by the liberties taken by its production team, as well as the sensation of having sold her artistic independence for a (healthy) sum.

To round out this experiment, the flesh-and-blood Bechdel has brought back some of her character from Dykes to Watch Out For, the influential 1980s comic. In the author’s imagining, after the passage of time, these fictional characters have moved to a community near the fictional Bechdel.

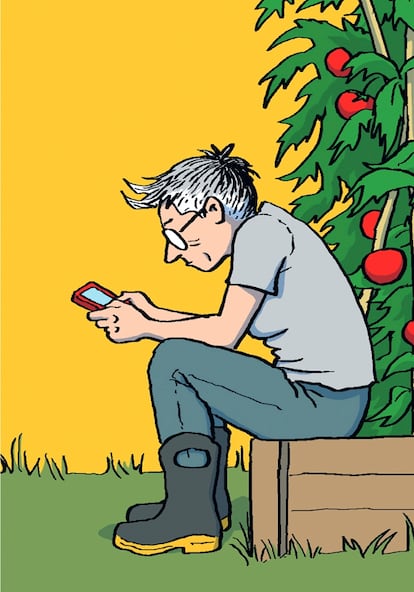

The result is Spent (Mariner Books), an entertaining reflection on the contradictions of always being on the side of the good guys, the traps of capitalism, the withering of ideals with the passing of the years, and the concessions that one makes with age — in addition to being a brilliant telling of what it means to be alive, in a liberal environment, in Joe Biden’s United States. It also speaks to the difficulties of concentrating in a world flooded with news, a sensation that the illustrator sums up with her customary brilliance via vignettes in which headlines from the era (about monkeypox, Donald Trump’s legal battles, and the Supreme Court’s anti-abortion ruling) hover in the air like the stench of a rotten bomb.

The responsibility for this fictional and non-fictional predicament lies with Karl Marx, according to Bechdel’s explanation in an interview that took place a few Sundays ago in New Haven, Connecticut, two days before her 65th birthday.

After publishing her last graphic novel, The Secret to Superhuman Strength, which has to do with the obsession with exercise, Bechdel thought about “writing another normal autobiography,” something like her previous works. The masterful Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic was the first of her existing three graphic novels. It’s a story about the author’s bittersweet relationship with her father, a closeted gay man and the director of a funeral home (hence the book’s title) in deep Pennsylvania.

“This time I set out to seriously investigate capitalism to reflect on my life,” says Bechdel. Her plan originally included reading Marx’s Capital, but she couldn’t get past the table of contents — though she did borrow its chapter names for Spent. She abandoned the project when it occurred to her that it was going to have to study things, like the economy, in which she was deeply uninterested. And so it was that she decided to give up and try her luck with auto-fiction, a form of expression less worn out in comics than in novels. And so, her protagonist is a cartoonist working on a book about the corrupting power of money.

As consequence of this shift, her latest work is “vastly lighter” than previous titles. “I would say maybe, maybe a little too light,” she says in an elegant room in Yale University humanities department.

She lives in a diminutive cedar cabin in the forests of Vermont, where in the depths of winter, the only way to get around is on skis. At Yale, she is teaching a course on comics that, she says, she’s had to make up as she goes. She teaches her students things that they “don’t really have to be a strong artist” to express their ideas. To prove it, she opens up her computer during the interview and looks up a picture of notes that underground legend Harvey Pekar made on a napkin when the two met in Cleveland, when he invited her to draw from them one of the short stories in his American Splendor series. “It was my first big break,” she recalls.

‘Dykes to Watch Out For’

On the strength of her weekly strip Dykes to Watch Out For, which began in 1983 and was inspired by her friends from the years she lived in New York, Bechdel was ushered into the U.S. independent comic club alongside her heroes, from Robert Crumb to Art Spiegelman. At the time, its only members were men, and she brought to it a queer and feminist point of view, particularly with the introduction of the “Bechdel test,” perhaps the author’s most lasting contribution to popular culture.

The idea comes from a 1985 Bechdel strip in which a friend tells her that she only watches films that fulfill three prerequisites: they feature at least two women, who talk to each other, and about something other than a man. The character’s latest example is Alien, in which its female characters speak to each other about a monster. From then on, the Bechdel test has been used to analyze all kinds of media products — not just audiovisual works. It’s a litmus test for the representation of women in popular culture.

Dykes to Watch Out For ended in 2008, when Bechdel had grown “tried of the regularity and also tired about the characters” — the same ones she brings back in Spent. “I guess it was sort of like a high school reunion,” says the creator. “Except that these characters are exactly the same. They’re all working for these various nonprofit organizations, trying to save the world. But it was fun to imagine how they would have physically aged. It’s such a bizarre thing, getting old.”

Bechdel did not bring back the entire gang, just Lois and Ginger, who join non-binary student J.R. and their parents Stuart and Sparrow, a heterosexual couple who decide to try out a polyamorous experiment with Naomi, an old acquaintance. They call this arrangement a “throuple” and not a “polycule,” saying that the latter sounds like a skin disease.

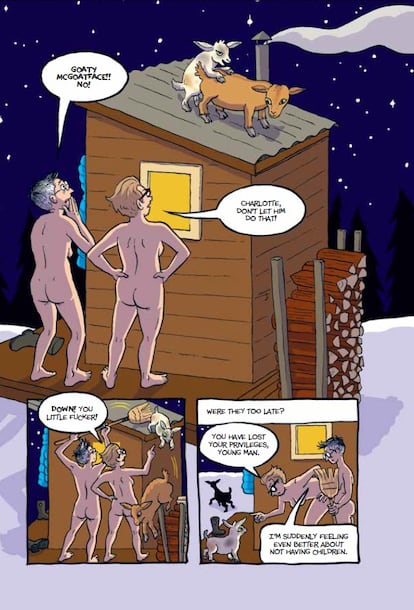

The plot of Spent takes place between 2021 and 2022, and the group wears masks and takes coronavirus tests when they have a gathering at a home that has a Black Lives Matter sign on the porch. Alison and Holly have a dwarf goat sanctuary (this is also fictional — Bechdel hold no particular affection for the animals). They buy absurdly expensive organic food amid galloping inflation and play a new game called pickleball. Alison gives talks on books that have been banned by the Republicans and they celebrate a “decolonial” Thanksgiving at which they dine on Tofurky cut with an electric carver. One character jokingly laments that Fox News isn’t there to document the meal, as another imagines headlines about gender ideology mixing up tofu with turkey.

All told, the gang fulfills every stereotype pertaining to what the right has disparagingly termed “woke culture.” Does Bechdel think an unsuspecting reader might misunderstand the comic’s tone of malicious satire? “Yes, and that’s fine. They have their foibles, but they’re so well-intentioned. You show their contradictions, or our contradictions, but not for the purpose of exposing them. I completely endorse all their views.”

The cast is rounded out by a Trump-supporting sister named Sheila and Holly, the protagonist’s partner, who rises to fame as a rural influencer and is inspired by Holly Rae Taylor, Bechdel’s real-life partner. Taylor is in large part responsible for the cartoonist’s journey into color, as Bechdel begun her career (before technological advances allowed for any other option) expressing herself in fine-line black and white. This comic is the second to feature Taylor’s optimistic palette, which is inspired by Tintin. “It was so generous of [Holly] to let me do this at all, even if it’s a fictional version of her. We were working together constantly. Because she was doing the coloring, I would be giving her the black-and-white line art, and we’d have to talk about everything,” says the cartoonist.

When it comes to the book’s sister — who is cradled in the arms of the MAGA movement, pro-life and convinced that children are being indoctrinated in their schools — the character is pure fiction. Bechdel does have two brothers, but she’s always tried to leave them out of her work. With this character, she’s made a clear attempt to build a bridge to the other America. “We’ve gotten so polarized in the United States that we’re unable to see each other’s humanity,” says Bechdel. “I wanted to try to do that with this character, who is trying to ban Allison’s book in in the school district where she lives, but also they’re connected. They’re sisters. They have this family history.”

Confrontation has reached new heights after the murder of MAGA youth leader Charlie Kirk, which took place three days after the interview. In an email she answered on September 10, Bechdel responds to two questions: Does she think that the two Americas are definitively doomed to not being able to find a common ground? And how does she feel about Trump and his allies’ rhetoric about the so-called radical left being the only one to blame?

“It’s really scary, I won’t lie,” the author replies. “This week has been especially crazy. But I’m also hopeful that the worse things get, the more likely we are to find that common ground. Trump’s power depends on keeping us divided, keeping us from seeing that we’re all in the same sinking boat. As more and more Americans all along the political spectrum are being hurt by his policies, the clearer it will be to everyone that the real problem is the lunatic at the helm.”

During the meeting in New Haven, the artist responded to another question: What does she think the radical women of Dykes to Watch Out For would think of the new book’s conciliatory discourse? “Probably some of them would think I was selling out or being somehow intellectually dishonest,” says Bechdel. “But some of them would probably get it. I think that’s part of the book. You know those criticisms and you apply them to yourself, and then you try to make fun of them.”

Critique might also stem from the fact that, since her book before Spent came out, Rupert Murdoch, owner of Fox News, bought Bechdel’s publishing house Mariner Books. “I said yes to this deal because they were giving me a lot of money that I wouldn’t get from another publisher. I thought about [switching publishers] for a little bit, but I wanted to reach people, too. If I hadn’t taken that deal, not as many people would have seen the book. As I’ve gone through my career, I’ve made different kinds of compromises, and that was what I really wanted to write about. What do we compromise? Where do we draw the line?”

The book also explores activism in the settled later years of life. “I often wonder about [whether I’ve softened my progressive views],” she says. “I feel like, on the surface, no, but part of me is on that journey. If anything, I understand more and more clearly that progressive politics are the only way to save this planet, the only way to steer us out of this terrible skid. But I am understanding more clearly that we [the left] have failed at connecting with so many people, and I don’t know how to fix that. Part of me thinks yes, we went a little too fast. There’s this concept of how politics is being driven by certain groups, that people were just listening to the elite activists. I do think that did a lot of damage.”

Bechdel has also been disappointed to see how the companies that linked themselves to progressive causes five years ago after the murder of George Floyd are now pulling back amid the White House’s attacks on DEI policies. “It was just just for business. That’s something I wish I’d gotten into the book, the way that the gay movement made so much progress, in large part, because people get advertised to us. It started in the 1990s,” says the illustrator, who adds that for the first time, she’s afraid that the 2015 marriage rights legislation could be in danger. “If your rights rest on your buying power, that’s not a good situation.”

She was frustrated by Biden’s stubbornness to remain in the presidential campaign, and by the eventual defeat of Kamala Harris, a candidate she had come to be genuinely been excited about. “I sent so much money to [the Democrats] last year. Since the election, I’m finding other ways to donate to people.” It was difficult for her to accept that the party had lost its way — but not so Bernie Sanders, the senator of Vermont. She doesn’t know him personally, but she admires him and just illustrated the cover of an upcoming biography about his younger years, the image of which she proudly shares on her laptop screen.

With Trump in the White House, she has returned to her practice from his first administration of limiting her news consumption so as not to lose hope. “Part of me does feel optimistic,” she says. “I feel like things are so bad, people are going to have to put a stop to this. But so far, I don’t see it happening. It’s so fast and so global what they’re doing. I don’t actually feel depressed, which is amazing to me. I’m still waiting to find out how do we live now? I’m very happy that I have a job that’s very demanding, and I come and teach these young people, and that gives me a sense of purpose. Beyond that, I’m not quite sure what I should be doing.”

For her next project, she’s mulling over a sequel to Spent, with the same characters “living through the Trump years,” Bechdel says. “But maybe it’s too early.”

In the final chapter of Spent, the Alison Bechdel on paper cuts her garden’s lilies after an unseasonably warm winter as she asks herself about the possibility that the American experiment is slipping towards disaster in the upcoming elections. But the sun continues to rise, she concludes.

And that’s the important thing, signals the flesh-and-blood Bechdel before bidding adieu to the interview and losing herself in the soft rain among the colonial streets of New Haven. The following day, the sun did indeed come out.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.