Palestinian cartoonist Mohammad Sabaaneh: ‘The blood on the streets of Gaza cannot be erased from our memory’

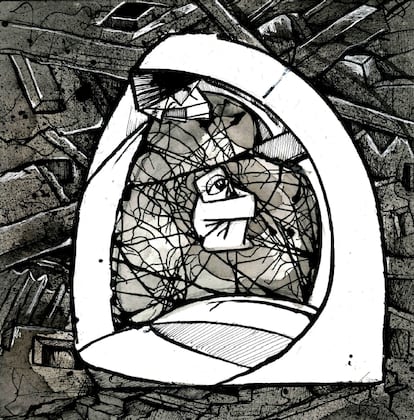

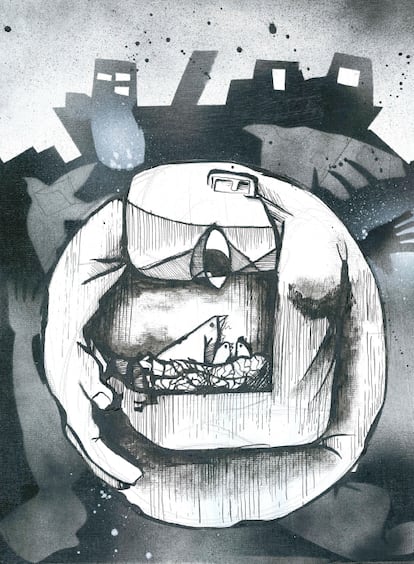

The artist has published a book featuring black-and-white illustrations created with a unique permanent ink. These drawings are inspired by videos shared by Gazans on social media since the onset of the war

Thirty seconds. That’s the length of the videos that Gazans have been posting on social media that have been capturing the horrors of their reality for over a year. These videos, numbering in the hundreds, typically remain on their profiles for only a few hours or days before being buried by new content or removed by algorithms.

“Some people feel unable to watch the videos to the end because they find them too distressing. Can we not even bear to see half a minute of someone’s life? What can we expect in that case?” reflects Palestinian cartoonist Mohammad Sabaaneh in an interview with EL PAÍS at Casa Árabe in Madrid, just hours before the presentation of his third book, 30 Seconds in Gaza.

A father weeping over the bodies of his children, a child searching for his mother after a bombing, dead babies covered in rubble, and adults desperately trying to shield the little ones — these are the haunting images depicted in the 92 illustrations, all in black and white and hand-drawn with a special indelible ink. Behind each illustration lies a name and a true story that has occurred in Gaza since October 7, 2023, explains Sabaaneh, a cartoonist for the Palestinian Authority’s Al-Hayat al-Jadida and London-based Al-Quds Al-Arabi newspapers.

The first question of the interview is both posed and answered by him: “Have you seen the photos of the people who were burned alive last night in the bombing of the Al Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Gaza? It is evident that Israel is targeting all Palestinians. It seems they had a plan for the Gaza Strip even before the attacks on October 7, 2023, and they are now putting it into action and no one is going to stop them.”

Question. Why do you see Gaza in black and white?

Answer. In my daily work as a newspaper cartoonist, I use color and work digitally. But in this book, the idea is to provoke a reaction in people regarding what is happening in Gaza. I think that black and white, the kind of ink I use and working by hand, without screens or technology, better represents what is happening and makes me feel more in tune with what I want to tell.

Q. What’s special about the ink?

A. It is Indian ink, made from fine soot. It has a special texture, and above all, it does not wash away with water. It is permanent. Because the blood on the streets of Gaza cannot be erased from our memory.

Q. Are all the illustrations inspired by a true story?

A. They all originate from videos and photos from Gaza that I have seen on social media over the past year. Those videos will eventually be lost. That is why I have made this book, to preserve Palestinian memory and to serve as proof of Israeli crimes against Palestinians in Gaza. Yet another piece of evidence... I don’t know how much more it will take for the world to react.

Q. Was there any cartoon that was especially difficult for you to draw?

A. They are all hard, because they all have a story, a name and a family behind them. They may seem repetitive, but they are not. I started drawing when I heard that there are people who do not feel able to watch the videos until the end because they find them too hard. We can't even see half a minute of a person's life? What can we expect then? That's why I wanted these images to remain forever. So people can't say they didn't know.

Q. Has this war changed your way of drawing?

A. There are different styles in the book, but above all there is a lot of cubism and inspiration from Pablo Picasso, because what happened in Guernica [when the Basque town was aerially bombed during the Spanish Civil War] and what is happening in Gaza every day is similar. Also, I thought that if people are familiar with the style, perhaps they will be more moved by what they see. What is clear is that in this book I have drawn differently, more compulsively, because as the war progressed, everything became harder and harder for me.

Q. Explain some of the illustrations.

A. This one, for example, is a child leaving the hospital, and it’s inspired by a video of a boy, aged around 13, injured and covered in dust, telling the doctors: “I’m fine, I’m fine.” Imagine, a child in those circumstances saying that he’s fine. This reflects... [sighs] not only his strength, but that he has no other option but to convince himself that he has to carry on. This other one represents a mother carrying the corpse of her son, who is just a child, on a wheelbarrow as she goes to bury him. A mother should never bury her child. We cannot get used to these atrocities.

Q. Are we getting used to the atrocities?

A. I think that what is happening in Gaza is as terrible and shocking as the fact that the international community is doing nothing to stop it.

Q. You live in Ramallah, in the West Bank. How has the war in Gaza been perceived from the West Bank? Are there Palestinians who prefer to turn a blind eye?

A. Some do. But not only in relation to what is happening in Gaza, but in relation to what is happening in Jenin, for example, where my family is from. People do not understand that what we see in Gaza today affects us all and could happen tomorrow in Tulkarm, Jericho or Ramallah. This Palestinian division is also a victory for Israel. But the problem is that we do not have leaders who unite us as a people. The Palestinian Authority sometimes fosters this separation and promotes the idea that our destinies and those of the people in Gaza are distinct, even though that is not the case.

Q. This past year, the living conditions for Palestinians in the West Bank have also worsened.

A. A lot. Before, for example, you could drive from Ramallah to Jenin and you wouldn’t see the Israeli settlements. They were further away, but now you can see them. The settlers have better public transportation and roads in the West Bank than we, the Palestinians, who are on our land. If nothing changes, in a couple of years, we will practically be guests in the West Bank, or worse than that, because guests are treated well and respected. We will be foreigners or visitors in our own home, because at the moment, there is no limit to what Israel will do.

Q. Have you had any problems with the authorities because of your drawings?

A. Yes, I have had problems with the Palestinian Authority. In the past, I was temporarily suspended from work and threatened. I have also been blacklisted by Hamas and spent six months in an Israeli prison.

Q. Do you feel free when you work, or do you censor yourself?

A. Nobody works freely. And the problem is not just Israel. We do not have freedom of speech to criticize whoever we want.

Q. There are topics you don’t touch on in your work, such as religion. Why?

A. I had problems when I did a cartoon of Mohammed years ago, but more than anything, religion is not my priority. It would be like talking about climate change when you have Israeli tanks just a short distance from your house.

Q. What is your priority?

A. To describe the human condition in Palestine. Beyond our political rights, which we also yearn for, what is important now is that our most basic human rights are respected. My brother has been imprisoned since before October 7, 2023 in an Israeli prison. Without formal charges, without seeing a judge, what Israel calls administrative detention. It is as if he were kidnapped. If we say that the Israelis held in Gaza are hostages or kidnapped people, we must acknowledge that there are also Palestinian detainees in Israeli prisons who fit that description. In our family, we have been trying to bring him a pair of glasses for a year, because his broke, but they have not given us permission to do so.

Q. Your work is always based on reality. Are you not attracted to fiction?

A. I don’t need fiction because reality is an immense and overflowing source of inspiration. With this genocide going on, all I want is to confront people with what is happening. It is already powerful enough, even if it ultimately appears not to be, as no one seems to react.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.