Art Spiegelman: ‘Banning books never works. It ignites interest in the forbidden’

The cartoonist speaks to EL PAÍS about the recent controversy sparked in Tennessee over his masterpiece ‘Maus,’ attributing the episode to ‘a cultural trend in America’

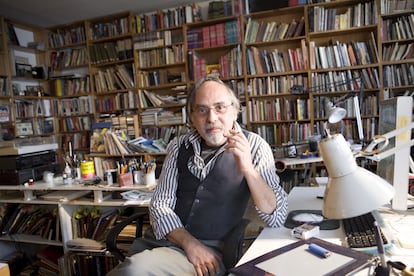

Art Spiegelman, 73, describes himself as a “First Amendment fundamentalist,” alluding to freedom of expression and religion. “Just like those religious fundamentalists in Tennessee.” The famous cartoonist is talking about members of a local school board in McMinn County, Tennessee who recently decided to remove his masterpiece, Maus, from the middle school curriculum. The acclaimed graphic novel about the Holocaust is based on the memories of Spiegelman’s father, a survivor of the Auschwitz concentration camp.

The author was left wondering whether the board adopted the decision out of “pure ignorance or simple malevolence,” as he explains to EL PAÍS via a video call from his home in New York. “But, you know, this is a free country.”

The school board’s ban was based on eight swear words and one scene of nudity. Spiegelman, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992 for Maus, believes that board members were offended by the images rather than the text.

“One was a discussion by my father with a premarital affair. She’s trying to stop him from leaving, by holding on to his legs. The other was really a picture of my dead mother [also a Holocaust survivor] in the bathtub that she killed herself in by cutting the wrists in the hot water of the bathtub,” he explains, holding an e-cigarette. “And you can kind of see a little dot that represents a nipple and a breast. Only somebody who reached the age of 14 without seeing a dot before was going to be surprised that this was happening.”

His first thought was that “this is just part of the crazy anti-semitism that keeps coming up in America. They’re trying to stop any discussion about these issues, because it’s too disturbing, to avoid conflict.”

This suspicion is shared by the well-known Holocaust historian Deborah Lipstadt, who has been designated by US President Joe Biden as the Special Envoy for Monitoring and Combating anti-Semitism. She said that “today’s rise in anti-semitism is staggering,” in remarks made before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on February 8.

Spiegelman is aware that the last Shoah survivors are dying. But he also doesn’t think that those parents on the school board are walking around “with swastikas on their armbands or anything like that.

“I think it’s part of a cultural trend that exists in many places in America, that takes the Bible literally. It’s in the same area where they had the Scopes Monkey trials in 1925, just 35 miles away from where the school board was, where they were trying to make it illegal to teach Darwin in the school because the Bible tells you that the world is only 3,000 years old.” This trial was captured by director Stanley Kramer in his memorable 1960 movie Inherit the Wind.

America’s romance with forbidden books has a long history that goes all the way back to Huckleberry Finn (1884) and Darwin’s The Origin of the Species, which was banned in 1895 for violating Christian beliefs. These days, there is a cultural war being waged in classrooms and school districts from Florida to Virginia and Pennsylvania, where books are being pulled from curriculums and public libraries because of their anti-racist or LGBTQ+ subject matter – books such as Toni Morrison’s Beloved or Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home. “They don’t seem to know that banning books never works,” he says. “It ignites the interest in reading what is forbidden.”

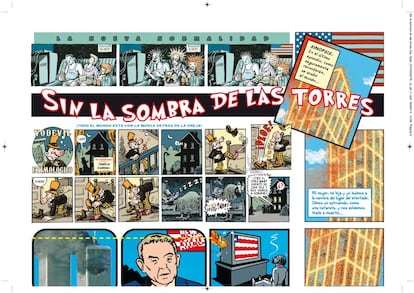

The cartoonist’s allegiance to freedom of expression also has a strong tradition. He began as a teenager, speaking out in favor of the National Socialist Party of America’s right to demonstrate in Skokie (Illinois), a town that was then home to the largest concentration of Holocaust survivors after New York. (The Supreme Court ruled in their favor and the lawyer representing the neo-nazis was Jewish.) Later, in the 1980s, as a leading member of the underground comic book scene, and always ready to push the boundaries of discourse, Mexico banned his Garbage Pail Kids, a humorous take on the popular Cabbage Patch Kids dolls. Much later, he had difficulty finding an American outlet to publish his comics about 9/11, In the Shadow of No Towers. And in 2015 he was caught up in a controversy with the British publication The New Statesman, which he describes as an organ of the well-intentioned left, when he retracted a cover he had submitted (titled “Saying the unsayable”) after the magazine refused to print a strip in which Spiegelman reacted to the massacre at Charlie Hebdo, the French satirical publication that controversially depicted Muhammad. He defended freedom of expression as also being “the right to act like an idiot.”

Despite so many precedents, the Tennessee case took him by surprise. That is why he took the time to “very carefully” study the minutes from the debate at the school board, which have to be public by law, while at the same time watching sales of Maus break new records. The trend is global, but especially intense in the US, where lately it has been impossible to find a copy. In fact, he has already decided where he will spend this added revenue: “I now have more money to commit to voter-registration campaigns and things like this to protect the future of our democracy”. “If you try too hard to protect your children, you actually make them really vulnerable because there’s no way for a kid to grow up into an ethical empathic adult without being exposed to the difficulties,” he argues. “One of the most shocking commentaries was to say what’s really disturbing are all these hanged mice and children being killed. It’s referred to by one board member because I studied the minutes really carefully. And it sounds absurd, like why should our children have to see this? Well, if it’s about the Holocaust, you have to show what happened. And I tried very scrupulously to do this without sensationalizing things.”

To narrate the unspeakable in Maus, which was first published in War, the magazine that he and his wife Françoise Mouly published in the 1980s, Spiegelman chose to use animals as characters. The Jews were mice, the Poles were pigs (there were also a couple of French characters who were dogs). He recalls how he got the idea for it. “And it was about just drawing anthropomorphic characters and I was having trouble finding a way to do this that would be meaningful, until I saw in a film class of somebody who was really my good friend, a professor of cinema. So I went to this film class and he was showing racist animated cartoons. You know, the minstrel kind of stuff. Some humans depicted as monkeys. And then he showed the sound cartoon Steamboat Willie [1928], with Mickey Mouse. And so after showing these race caricatures, he shows Mickey Mouse who was not the nice suburban mouse of the ’50s and ’60s who grew up to become an international logo. And then I thought I really have a way in because I will do a comic about race in America, with these oppressed black mice by the Ku Klux Cats.”

For a few days he was sure that he’d had a really brilliant idea... until he realized that it would probably be misunderstood or viewed as racist, or in the best of cases, as the product of the damaged mind of a white liberal underground cartoonist. “Then I realized I could tell the story of my parents, and my family’s bloody run, using that idea. So I found this universal metaphor of racial oppression.” He also found inspiration in George Orwell’s classic anti-authoritarian tale Animal Farm, which Spiegelman notes gets often included in the list of banned books.

Maus gave him problems from the start. When he published it, “there were Jewish organizations very unhappy because the Jews were shown as meek little mice hiding only, not having a resistance. ”Many people failed to understand that behind the zoomorphism there were people wearing masks. “By the time you read the whole book, it’s clear that Maus is constructed as a self destructing metaphor. It’s a stupid metaphor. It’s Hitler’s metaphor. So I was working with it to demystify.”

Part one of the two-part graphic novel opens with a quote by the Führer: “The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human.” Claude Lanzmann, director of the 1985 documentary film Shoah, approved Spiegelman’s strategy. “Or at least it looked like he liked my work,” notes Spiegelman.

The book also ran into trouble in Russia (where it was banned as “Nazi propaganda”) and in Poland, where the project to publish it was cut short several times, Spiegelman recalls. Finally it was Piotr Bikont, a journalist from the Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza, who dared to found a publishing house and put it into circulation. As a reward for his daring, a book-burning session was organized for him at the door of the newspaper, and Bikont came out to greet the demonstrators from the balcony behind a pig mask.

Spiegelman is amazed that this kind of thing is still happening: four days after the ban of his comic book made global headlines, a pastor named Greg Locke organized a book-burning session in Nashville, Tennessee that included books from the Harry Potter and Twilight series, which were described as “satanic.” The event was streamed on Facebook.

“So they had a big book-burning and it was published next to a picture of a book burning in Germany in 1933. And the only real difference between the two is that one was in color. That person is an idiot, really terrible person, not just an idiot, but a malevolent idiot that thinks that Covid was a hoax, and more people, as a result, got to die. He also believes that Trump won the election. Those people don’t realize that it is ineffective, unless you’re willing to go all the way after burning the books, and burn the writers and readers who are involved with these books.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.