Robert Capa’s iconic Spanish Civil War photo: A mystery that endures 90 years later

The Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid is hosting the largest retrospective in Spain of the photographer’s work, with 250 pieces, including images, publications, and objects on war and life

Robert Capa (1913-1954) is the great legend of war photojournalism. He photographed the Spanish Civil War, World War II, the Sino-Japanese War, and the First Indochina War, where he lost his life. He always sought to fulfill his maxim: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” He also forged his legend thanks to his personality: a people person, with an ironic sense of humor, a bon vivant, a drinker, always with a cigarette in his hand or in his mouth, he lost the large amounts of money he earned in poker games that lasted until dawn. Almost always chasing a girl, he was Ingrid Bergman’s partner. A complete overview of his two-decade career can now be seen at what its organizers bill as “the largest Capa retrospective in Spain,” at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid.

The exhibition, titled Robert Capa. Icons, co-produced with the ticket sales platform Sold Out, brings together more than 250 pieces that will be exhibited until January 25, 2026, including photographs, some of them originals developed by Capa himself; newspapers and magazines that published his photos; and objects, such as his typewriter or one of his cameras, a 1930 Leica. All of them come from the Magnum Photos agency and the Golda Darty collection, one of the most important private Capa collections in the world.

However, the focus of the exhibition, at least during its Spanish stop (it exhibited at Les Franciscaines Deauville last year), is on the various copies of the famous photograph, The Falling Soldier, from the Spanish Civil War. The exhibition’s curator, Michel Lefebvre, who was a journalist for Le Monde where he wrote about contemporary history, discussed the various hypotheses surrounding the photo: Is it real or was it staged? Where was it taken? Who was that militiaman? Ninety years later, “it remains a mystery.” “This photo is the Mona Lisa of photojournalism.”

Lefebvre, author of the book Robert Capa, les empreintes d’une légende (Robert Capa, the footprints of a legend), recalled that for a long time it was said to have been taken in Cerro Muriano (Córdoba) and that the victim’s name was Federico Borrell García. However, a few years ago, a Spanish historian, Fernando Peco, demonstrated that the photo was taken in Espejo, a municipality in Córdoba 30 miles from Cerro Muriano. “We don’t know the date it was taken, or who the militiaman was, or if he died. Medical experts say that you can’t fall like that from a single gunshot wound. Furthermore, the militiamen prepared the photos for the reporters, and we don’t have the negative either. Capa said he was there and that there was some fighting.” It was published on September 23, 1936, in the French weekly Vu.

Not long before that photo was taken and Capa’s world-famous status was established, his name was Endre Ernö Friedmann, a Hungarian from a Jewish family who had fled his country for Berlin after being arrested for communist activities. After Hitler’s rise to power, he moved to Paris. As the curator notes, “At the beginning of 1936, he was living in poverty in Paris; his friends had to give him a coat; his mother sent him money.” He and his partner, fellow photographer Gerta Pohorylle, another Nazi fugitive, invented the pseudonym Robert Capa. And she adopted the pseudonym Gerda Taro. They say that Capa is a glamorous U.S. photographer who takes great photos, which in reality they both take. Thus began the myth. When the Spanish Civil War breaks out, as defenders of the Republic, they move to Barcelona.

The first photographs in the exhibition are those with which Capa made his mark in the field, thanks above all to one of the revolutionary Leon Trotsky during a rally in Copenhagen for the Berlin agency Dephot in 1932. In this vein, he portrays the workers of Paris. It’s already clear that he’s interested in showing people, not what’s happening around them.

In the section dedicated to the Civil War, in addition to the soldier, there is another famous image taken in the Madrid neighborhood of Vallecas of three children sitting peacefully in front of a single-story house, its facade riddled by shrapnel. It’s a place that the Anastasio de Gracia Foundation, affiliated with the General Union of Workers (UGT), and a neighborhood organization have wanted to convert into a museum dedicated to Capa for years. However, Madrid City Council has decided to make it a cultural center.

Without Gerda Taro, who died in an accident, crushed by a Republican tank in July 1937, Capa would cover the World War. After covering the campaigns in Algeria, Tunisia, and Sicily came the world-famous photos he took when he accompanied U.S. soldiers on Omaha Beach during the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944. When he began to see corpses around him, he said, “This doesn’t look very good, man.” Those historic images were damaged in the laboratory (another Capa legend: what exactly happened?) making them blurry. Seven of the nine surviving photographs are on display. Precisely, with his wry humor, he titled his autobiography Slightly Out of Focus, alluding to that development disaster. The book, at times very funny, “doesn’t tell the real story of Capa; he makes up a lot of things,” Lefebvre notes.

He portrayed the liberation of Paris by the Allies in August 1944, with its jubilant people saluting the soldiers, and its counterpoint, the image of a woman with her head shaved by her compatriots, holding the baby she had had with a German soldier. Andrea Holzherr, Global Director of Exhibitions at Magnum Photos, recalled that the starting point for this traveling exhibition was the 80th anniversary of the liberation of France, celebrated last year.

Meanwhile, the director of the Círculo de Bellas Artes, Valerio Rocco, noted that this exhibition serves to “remember the brutality of wars and the importance of journalism in reporting on it.”

The last conflict Capa documented was the First Indochina War. It cost him his life at just 40 years old, when he stepped on a landmine on May 25, 1954, in Thai Binh, Vietnam.

The exhibition changes its look for the section the curator calls “Capa in Peacetime.” It features his color work on fashion and travel for magazines like Life. It feels like entering another planet, with the solace of the aristocracy on the beaches and racetrack of Deauville, on the Normandy coast.

In May 1947, Capa and other photographers, like his friend Henri Cartier-Bresson, had founded the Magnum agency. “Capa was its driving force,” said Holzherr, who also recalled the myth surrounding the agency’s name. “It’s said it’s because of the one-and-a-half-liter bottle of champagne they opened to celebrate in a New York restaurant.” The truth is that Magnum was created “so that photographers would have control over their work and their copyright.”

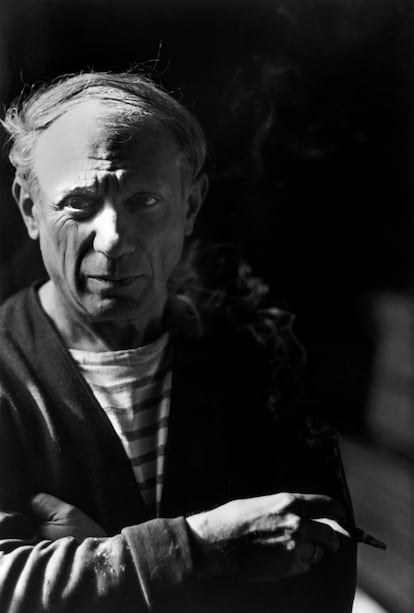

And finally, a room of portraits. As Lefebvre says, “When he wasn’t in war, he showed that he was a photographer who could do everything.” Picasso, John Huston, Hemingway with a bottle, Ava Gardner on the set of The Barefoot Contessa, Truman Capote with a dog in his arms, and, of course, Ingrid Bergman. They were in love, but she was in love with Hollywood, and he led a nomadic life.

Finally, Lefebvre announced that contact sheets containing photos of Capa and Taro had recently been discovered... “There are no negatives or copies of half of all this, but it will be the subject of an upcoming exhibition in Paris in 2026. With Capa, you’re never bored.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.