How Stalin pressured Mexico for Trotsky’s deportation

EL PAÍS takes a look inside the archive reflecting fruitless efforts to get the revolutionary deported

While an elderly Leon Trotsky cared for his beloved cactus plants and wrote about politics, Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas kept receiving letters requesting the deportation of the Russian revolutionary.

The exiled legend of the Russian revolution, the roaming scourge of the Kremlin, the man whom Stalin wanted to see dead, very much dead, had to be persecuted and harassed everywhere he went. And Mexico’s Stalinists certainly contributed to the strategy to bring down Trotsky.

A neighborhood association claimed he was “the leader of an international gang of muggers”

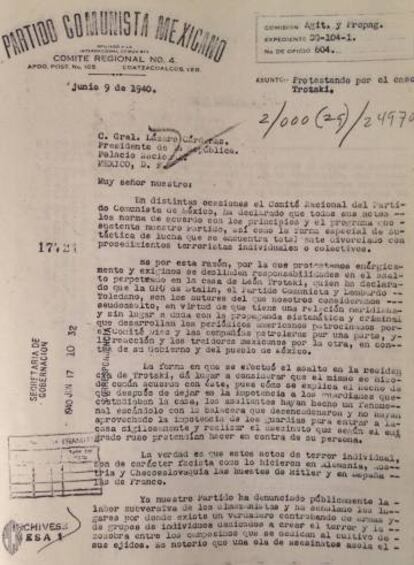

From every corner of the country where a Communist cell might be found, a telegram or letter was sure to be sent complaining about “that agent of oil companies and Yankee imperialism,” in the words of the Bricklayers’ Union of Papantla, a village in the state of Veracruz.

“We may assert that Trotsky has not brought Mexico any benefits, but instead has come here to slyly work against our good regime and to issue slanderous statements against Mexican workers,” wrote the Carpenters’ Union of Tampico.

The Alma Huasteca Society of Avant-Garde Students judged him to be “a dangerous foreigner […] whom all of Mexico’s youth is complaining about, out of fear that he will engage in shameful political intrigues in this country.”

And the the Municipal Women’s Committee of Arcelia, in the state of Guerrero, considered him “workers’ number-one enemy.”

Most of these letters petitioned the president to kick Trotsky out of Mexico. One group with a mouthful of a name, the Regional Committee for the Defense of Nationality Against Imperialism and Reaction, sent Mexican authorities a letter with a list of 11 priority issues the government should address for the good of the nation. The third point was to drive out Trotsky, and this came before other matters such as guaranteeing medical attention for Mexico’s peasant population, or ensuring access to clean drinking water.

The government files containing these letters are kept in the General Archive of the Nation. EL PAÍS has had access to the copies held by the Leon Trotsky Home and Museum, where the Russian revolutionary lived and died.

Most of the documents date back to the summer of 1940. In May of that year, a commando attacked the house, riddling it with bullet holes. But the target and his family survived the attack. Several Communist activists were arrested, and a wave of letters ensued in the following weeks in a bid to get the suspects released and Trotsky deported under Article 33 of the Mexican Constitution, concerning inconvenient foreigners.

The mastermind

Esteban Volkov, 90, is the director of the museum that bears his grandfather’s name and is a tenacious researcher of the historical facts surrounding Trotsky’s persecution and assassination.

Volkov asserts that the mastermind behind the attack was Vicente Lombardo Toledano, secretary general of the Workers’ Confederation of Mexico.

“He was on Moscow’s payroll according to the Venona files, a US intelligence program to decipher encrypted KGB messages,” he says.

Volkov is still grateful to Lázaro Cárdenas for not buckling under the pressure to deport his grandfather. “The Stalinists waged a tremendous campaign,” he says, adding that Lombardo mobilized all of his cells in order to flood the government with protest telegrams and letters.

“But Cárdenas held his ground. He would not take orders from Stalin or from anybody. He never once hesitated.”

But the archive also contains letters written prior to Trotsky’s arrival in Mexico. On December 7, 1936, the Alliance of Tramway Workers sent the government a telegram asking it not to let in “the world’s greatest counter-revolutionary, with ties to German fascism.”

Trotsky arrived by boat the following January and remained under the protection of General Lázaro Cárdenas, whose foreign policy made it a point of pride to grant asylum to exiles during those times of major global upheaval.

The letters contained all kinds of accusations against Trotsky. There was a neighborhood association that claimed he was “the leader of an international gang of muggers.” The Mexican Communist Party’s Yucatán State Committee accused him of working “as an agent of the English intelligence services.”

He was a “fateful instrument of International Imperialism” to the Mexican Committee in Favor of Reorganizing Schools and Redeeming the Blind. And a member of the Mexico for the Mexicans Club wanted Article 33 of the Constitution to extend “to all Spanish refugees living in Mexico.”

But Cárdenas ignored the campaign against his guest. The president never met personally with Trotsky because he did not want to give the Stalinists more fuel for their propaganda. He had no ideological ties to Trotskysm, yet never broke his personal commitment to provide Trotsky with shelter.

It all ended on August 20, 1940, when Trotsky was assassinated by Ramón Mercader, a Spaniard working for Soviet intelligence services.

Days after the legendary Bolshevik’s death, the Mexican government’s offices were still receiving letters complaining about him. Trotsky’s postal persecution had followed him into the grave.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.