The misunderstood spiral of kleptomania: ‘It gives momentary relief, but then guilt and shame set in’

A study describes the psychological disorder that lies behind the uncontrollable impulse to steal: it is very little studied and surrounded by a layer of stigma that complicates diagnosis

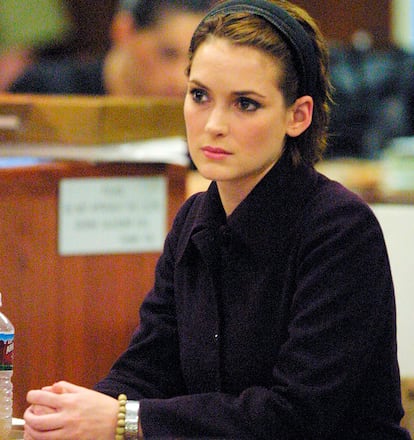

The new millennium had just dawned when images of actress Winona Ryder shoplifting from a department store spread worldwide. She was one of Hollywood’s hottest stars of the moment, and that episode — and the subsequent trial — made headlines around the globe. She was sentenced to a fine, community service, and therapy for treatment of alleged kleptomania. She never confirmed this disorder; she simply remained silent and disappeared for a while. Only years later did she reveal that, at the time of the incident, she was taking painkillers that had left her in a state of “confusion.” She didn’t clarify much further but her case served, with varying degrees of success, to bring kleptomania — a complex psychological disorder that is largely understudied by the scientific community — into the spotlight.

Doctors and psychologists describe it as an uncontrollable impulse to steal. An imperative, inevitable behavior. It’s not a theft to enrich oneself or enjoy the stolen goods. Sometimes the stolen goods are worthless or of no interest to the person taking them. These acts are usually motivated by a search for pleasure, satisfaction, or relief from committing them, followed by guilt and deep emotional distress. Lucero Munguía, a psychologist and researcher in the Psychoneurobiology of Behavioral Disorders group at Idibell in Barcelona, explains that it’s ego-dystonic behavior. That is, behavior that is contrary to the values of the person who commits it. “Before the theft, the person feels very strong emotional tension and feels compelled to commit the act in order to calm and relieve that tension. But it’s a downward spiral: at the moment, it relieves them and creates calm, but later, they experience many feelings of guilt and shame. It generates a lot of discomfort because the behavior is experienced as something very negative, contrary to their personal and social values.” The researcher has just led a study to more precisely characterize this disorder, which has a complex diagnosis and limited therapeutic approach.

Currently, kleptomania falls under the umbrella of impulse control disorders, which also includes, for example, pyromania or trichotillomania (characterized by irresistible hair-pulling behaviors). “It’s a difficulty controlling an action that, even though we know it has negative consequences, we can’t resist the impulse,” the researcher emphasizes. In their study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, Munguía and her colleagues explain that the prevalence of kleptomania ranges between 0.3% and 2.6% of the population, although it is hypothesized that it is underdiagnosed, precisely because of the weight of the stigma, guilt, and shame that these behaviors generate. It has also been observed that it is more common in women: three out of four diagnoses.

The causes behind kleptomania are multiple, experts point out. At the neurobiological level, Luis Giménez, a member of the executive committee of the Spanish Society of Psychiatry, points to the most studied neurotransmitter in this type of condition: serotonin, which is usually responsible for curbing impulsivity. “Kleptomania is multifactorial. There is a biological component, influenced by genetic markers or a serotonergic deficiency, but there is also a psychological component, as these individuals tend to be impulsive. That’s why we resort to serotonergic drugs and also antiepileptics, which curb neuronal excitability and reduce the desire to do something.”

A form of emotional regulation

In her study, Munguía also points out that first-degree relatives of people with kleptomania have shown a higher likelihood of presenting with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and substance use disorders. Individuals with kleptomania also commonly present behavioral addictions, such as gambling disorder, eating disorders, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. “You often see a very anxious profile, constantly trying to avoid harm. And then you also see a lot of emotional issues because, sometimes, these behaviors — and I’m not just talking about theft in kleptomania, but also in the case of behavioral issues and addictions, such as gambling or eating disorders — begin as a way of emotional regulation,” explains the Idibell researcher. This means that these types of behaviors are triggered in order to cope with stressful or painful life situations that are difficult to deal with. “They may begin as relief from that strong emotional response, but it’s not long-term relief. It’s temporary, and then you’ll return to the same situation, with the same triggering problem. In other words, it’s not a real solution, but it can be a way to deal with the emotion,” the psychologist explains.

It’s not clear why it affects women more. Gutiérrez points out that “impulsiveness in men is more closely related to testosterone and is more evident in substance use and aggressive behavior, while in women, impulsive behavior is less damaging, which is why kleptomania is more common.” Munguía points out that it may be related to this regulation in stressful situations, as women tend to be more emotional. But that’s just a hypothesis, the psychologist emphasizes: “Much research is needed because it’s a very understudied and underdiagnosed disorder. Right now, we’re seeing more women in consultations for this disorder, and it’s hypothesized that one of the components may be due to emotional regulation. But the truth is that we don’t know how many people actually have this illness because it’s highly stigmatized, and people don’t go to consultations; they hide it.”

It is very rare for a patient with kleptomania to seek medical advice of their own free will and be aware of the disorder. Typically, they come after legal problems, due to family pressure, or due to another associated disorder (such as an eating or behavioral disorder), and kleptomania is discovered during a clinical examination.

The weight of shame

The stigma weighs heavily on both diagnosis and therapeutic approaches. These behaviors usually appear very early, in adolescence, but patients develop them later in life, over 50, and with the disorder having developed for many years, says Susana Jiménez-Murcia, head of the Clinical Psychology Department at Bellvitge Hospital and co-author of the study. “All of this complicates the response to treatment; more than 65% drop out. But they’re no longer motivated to come; there’s no recognition of the disorder due to that shame. There’s no motivation, they don’t want to come,” she laments.

Munguía recalls that episode with Winona Ryder and the media and social stir it caused at the time: “This type of social judgment that trivializes and mocks it, which will create a meme here or there, causes those people, who are truly suffering, to not feel confident even talking about it to those closest to them.” The researcher recalls that a person with kleptomania “is a patient who is suffering a lot”: “We are more used to talking about mental health, but there are still disorders that are very difficult to understand and we have to make them visible to prevent people from continuing to suffer alone.”

In their study, the Idibell researchers have characterized a sample of their patients with kleptomania (13 people) and another larger group (71 people) with this disorder and another associated one, and have discovered that, in addition to traits of impulsivity, there may also be characteristics of compulsivity, a finding that can directly impact the therapeutic approach.

Jiménez-Murcia establishes the differences between the most impulsive and the most compulsive profiles: “They can’t avoid either. But the impulsive profile seeks gratification, which implies positive reinforcement, while the compulsive profile seeks relief, which implies negative reinforcement.” Munguía elaborates: “Impulsivity would be the most gratifying aspect: I do something without thinking about the consequences because it will generate gratification, or I am constantly searching for a novel stimulus because it makes me feel a kind of high at that moment. In the case of the most compulsive profile, they also can’t stop the behavior, but the motivation isn’t something they find pleasurable; it’s something that generates relief because they are feeling extremely uncomfortable for not doing it.”

Exposure or avoidance therapy

Depending on which traits are more prevalent, the therapeutic approach may be different. For the more impulsive profile, we work by avoiding certain stimuli to keep those sensations under control. For a person with more compulsive characteristics, a gradual exposure and response prevention strategy may be more appropriate: instead of avoiding the stimulus, we prepare them to be able to expose themselves to a risky situation and contain the impulse.

Jiménez-Murcia and Munguía assert that their findings in the study may help improve treatment response, which is currently very low, with high rates of abandonment and relapse.

Gutiérrez urges us not to trivialize these disorders. “Mockery produces guilt and shame. The person doesn’t steal because they’re a miser or because they can’t afford it, but because they can’t help it. Not understanding it and, furthermore, ridiculing it increases the stigma by 20.” The psychiatrist also points out that these conditions develop in adolescence and warns that today’s society is encouraging problems with impulse control and the constant search for novelty: “If a kid starts with impulsive behavior and doesn’t control himself, doesn’t master it, it will lead to many problems. If they don’t control these behaviors in the short term, they will experience mood swings, addiction, aggression... It’s all part of the same parcel,” he warns.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.