Families demand repatriation of bodies of Colombians who died in Ukraine: ‘This war is a slaughterhouse for foreigners’

The remains of hundreds of soldiers have yet to be returned to the country, and many claim they have not received the compensation promised by Kyiv

The last time Marta Sarmiento spoke to her husband was on a Friday. He had joined the Ukrainian army to fight in the war against Russia, drawn, like so many others, by the lucrative salaries. That day, Ricardo Velásquez told her he was going on a mission to the front lines. Worry immediately set in. “I cried all weekend, went to Mass, and felt terrible,” she says. Her feeling that something bad had happened was confirmed on Monday: he was dead. A Russian drone attacked him as he tried to escape.

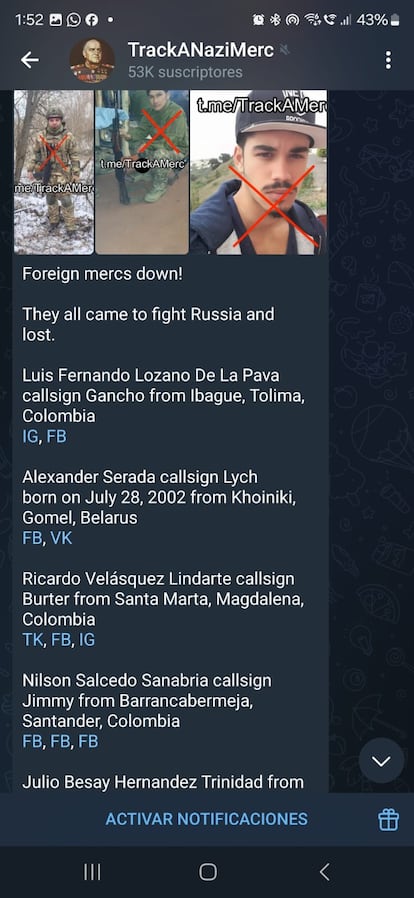

More than nine months have passed since then. Marta was able to confirm Ricardo’s death in March through the testimony of a comrade and a Russian Telegram channel that announces casualties on the opposing side. Despite this, he is officially listed as missing, yet she continues to receive his salary. To resolve her doubts, she traveled to Ukraine in June. She spent approximately $4,000 seeking answers, but returned with even more questions.

“Without a death certificate, we face many problems here in Colombia. The banks call us constantly, the authorities won’t leave us alone. Even though we know he’s dead, as far as the system is concerned, he’s still alive,” she says from Santa Marta, where she lives with her 12-year-old daughter. The human aspect is another agonizing one: “Without a burial, the grieving process is much harder. Several commanders have told me it’s very likely I’ll never recover his body.” Red Cross officials told her something similar when she went to Ukraine; that it would be a process that would take years.

Marta’s situation is escalating as the months of a war that began in February 2022 drag on, a war with no end in sight. Between 2,000 and 3,000 Colombians have volunteered to fight in the Ukrainian army, according to various estimates. The Foreign Ministry acknowledges that at least 300 Colombians have died, but the number is much higher, according to their families, if those who are still missing are included, as their bodies have not been recovered in Russian-controlled territory.

Marta now volunteers with an organization called The Voice of Those Who Are No Longer Here, which represents up to 250 families who, after confirming — officially or unofficially — the deaths of their loved ones, have begun demanding the repatriation of their bodies and the aid promised by the government led by President Volodymyr Zelenskiy to foreign volunteers. In early December, several of them demonstrated in downtown Bogotá to urge the Foreign Ministry to obtain answers from Kyiv.

EL PAÍS has spoken with seven families of Colombian fighters in the Ukrainian army who have died in recent months. The accounts from all the sources — almost always women — have several points in common: the recruits usually have military experience in Colombia and are lured by offers of high salaries from the Ukrainian authorities. They learn about the opportunity through social media, mainly TikTok, and soon go to war. Some are better prepared than others: some buy life insurance in case of death in the conflict and leave their assets in their partners’ names to avoid bureaucratic problems. Many of them are fathers.

José Elkin Valdés fought for more than two years in Ukraine. He had been a soldier in the Colombian Special Forces and was retired when he decided to join the war. His family says he wasn’t motivated by money, but by combat. “Being a soldier was all he knew. He joined the army at 18. When he left, he was 41,” explains his ex-wife, Yaderly Tique. They have a son, Alejandro, a law student.

The soldier was in constant contact with them until mid-June when he stopped responding to messages. They learned, through a fellow soldier, that he had been shot in the head. “[The Ukraine] war is a slaughterhouse for foreigners. In 10 years, no one will remember my father. Those who leave become a number in a statistic. They’ll be just another number on a commemorative plaque, not even a statue. And I ask myself: what for? So many homes are destroyed, and there’s no end in sight,” laments young Alejandro through tears.

This family’s case is unique. José Elkin married another woman before going to Ukraine, and she is the one who received the firsthand information. She was the only one who traveled to Ukraine for the burial, because the body was recovered. “She video-called us when they opened the coffin, and I saw him directly,” says Alejandro, who doesn’t know when he will be able to visit his father’s grave, much less if he will ever be able to bring him back to Colombia. Despite being his son, he hasn’t received a single peso in compensation for José Elkin’s death.

The Ukrainian embassy in Lima, which also serves Colombia, stated in a written response that “in the event of death in combat, family members are entitled to a one-time financial compensation.” The amount, established by law, is approximately $3,500 per month, paid in about 80 installments. The embassy acknowledges that “there are reasons why the disbursement may be delayed or not processed.” In the “overwhelming majority of cases,” it adds, this is due to a lack of documentation, although there are other exceptions. For example, a woman who lived in a common-law relationship with the deceased will not be compensated, because this type of relationship is not recognized in Ukraine.

Furthermore, the diplomatic mission explains that the category of missing person prevails “if the body has not been recovered and its identity verified with DNA,” even if there are photos, videos, or testimonies of a death. “Such bodies may be recovered later, when the front lines shift. The challenge is that no one in the world knows when recovery and identification might occur. Sometimes it takes days. Sometimes months. It can take several years. Even today, bodies from World War II are still being found in Europe.”

Angélica Morales’s case is one of the few success stories, if receiving a brother in a coffin can be called that. The body of Fernando Morales, who died aged 30, arrived in Colombia last week. His funeral was held on December 14. Angélica says he went to Ukraine at the end of August and she didn’t hear from him until October 30. As in many other cases, she confirmed, through the testimony of a comrade, that her brother had died after being attacked by a drone while in the trenches.

Having died in territory controlled by Kyiv, it was easier to identify and repatriate the body. In a letter reviewed by this newspaper, the Colombian Consulate in Warsaw, Poland, confirms that Fernando died on November 9. The document requested authorization to hire a funeral home to transport the deceased and perform an autopsy. The family also had to specify whether they wanted to receive the body or the ashes. They now treasure a video showing the arrival of the coffin in Colombia, wrapped in black plastic. “My other brother had to do the identification. Fernando’s face wasn’t the same anymore, so we confirmed it was him by his tattoos and a scar he had on his jaw.”

Angélica says her family “is fortunate amid so much tragedy.” “You see so many desperate families trying to bring their loved ones home, and many can’t. Having the body and having it buried helps bring closure.”

Several Colombians who have survived the war confirm the veracity of the common elements in these accounts. One of them states that the Ukrainian army pays more to recruits who choose to go to the front lines, and that this is why so many foreigners have died. This situation has already put Colombia on alert. Congress approved a bill to prohibit mercenary activity because many travel as private contractors. President Gustavo Petro still needs to approve it for it to become law, but this legislation does not cover those who volunteer for the national army of another state, as is the case in most instances in Ukraine.

On social media, primarily TikTok, videos are posted daily of Colombian fighters pleading with their government for rescue. These videos appear as the conflict drags on. Last Saturday, the Russian army announced it had “eliminated” a unit of Colombians in the border region of Kharkiv.

Marta says her husband was aware of the risks involved in enlisting. “He left me life insurance and his belongings in my name. But we know of many cases of farming or Indigenous families who weren’t aware of the risks and now have no way of even finding out that their sons have died,” she points out. Although she understands that her grief will be long, she feels even more sorrow for her daughter: “She doesn’t talk about it, but her psychologist tells me that one day that pain will erupt. It’s inevitable.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.