The plight of Colombians fighting for Ukraine detained in Russia after disappearing in Caracas: ‘They are not mercenaries’

The story of José Arón Medina and Alexander Ante, who fought in the war in Ukraine before stopping in Venezuela on their way home, remains shrouded in mystery

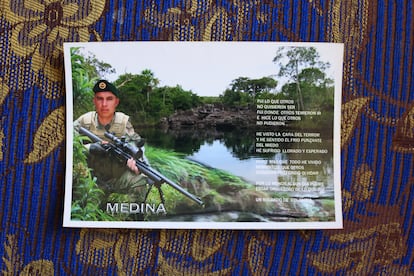

“Darling, we are here in Caracas.” A map with the geolocation pin of the Simón Bolívar International Airport in Maiquetía, Venezuela, where he was stopping over on his way back to Colombia after having fought for several months in Ukraine, that brief WhatsApp message, and a three-minute video call that ended abruptly on July 18 at 5:30 p.m. was the last Cielo Paz heard from her husband, José Arón Medina, during the six long weeks he was missing. It was not until August 30 that she received news of him, when she identified him in a video released by the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), the former KGB. Together with his comrade Alexander Ante, another Colombian ex-military officer who had fought in the Ukrainian army, they were arrested and accused of being mercenaries by a Moscow court, a charge that could lead to 15 years in prison.

What exactly happened in those six weeks, and when and how they traveled the more than 6,200 miles that separate Caracas from Moscow, remain loose ends due to the secrecy of the Venezuelan authorities. Their relatives have not received answers, and their petitions to the Venezuelan embassy in Bogotá were ignored. Ten days after their disappearance, on July 28, Venezuela held presidential elections, with Nicolás Maduro declaring himself the winner without providing any credible evidence of the result. Russia is one of the few countries that has recognized Maduro’s reelection. Moscow was also a financial lifeline when the U.S. sanctions blockade complicated the commercialization of Venezuelan crude oil, and as such Maduro has responded to the invasion of Ukraine with vocal support.

The Maiquetía airport has become a black hole in which the Venezuelan intelligence services operate with total freedom, a risky transit site where several arrests have been made in the last year. The apparent extradition of the Colombians has been shrouded in mystery. Both the Venezuelan Attorney General, Tarek William Saab, and the new Minister of Interior and Justice, Diosdado Cabello, have referred to the case of an American soldier detained in Venezuela a few days ago, but they have not said a single word about the Colombians, an episode that could affect relations between Bogotá and Caracas at a particularly delicate moment at which President Gustavo Petro insists on mediating to achieve a negotiated solution to the post-electoral crisis. In response to the formal request for information made by Colombia through diplomatic channels, the Venezuelan Foreign Ministry responded that it had registered their entry on July 18, and was not aware that they were detained in Venezuela.

Medina and Ante served in the Colombian army. They then spent several years doing security work in Popayán, the capital of Cauca, one of the departments hardest hit by the armed conflict in the country. In a telephone conversation with this newspaper, his wife describes Medina, before any other characteristic, as an excellent father. They have two children, one 16 years old and the other nine. “He really likes the army,” she says, recalling that he was a professional soldier for four years. Since leaving the forces 15 years ago, he had worked as a security guard until he accepted a lucrative offer to go to Ukraine, where he earned 12 million pesos a month (around $3,000). He left in November 2023 and spent eight months fighting in Ukraine, until he decided to retire. “He said he had already seen many comrades die and he was not going to risk his life anymore, so he decided to return home. But they never arrived,” says Paz.

She received the video through Medina’s comrades-in-arms still in Ukraine, and that is how his relatives learned that he had reappeared in Moscow, along with Ante. The Prosecutor’s Office had even published posters of them as missing. “We did not receive a single call from Caracas, we did not know what had happened, if they were alive or dead; those were distressing days, and until now we have had no communication with them,” Paz says. On Tuesday, she received a call from the Colombian consulate in Moscow to inform her that they would be assigned a public defender. She has asked the Foreign Ministry to help them get back to Colombia.

Alexander Ante, 47, and father of a five-year-old girl, had also been retired from the army for nearly two decades after 13 years in service and worked as a bodyguard in Cauca, says his brother, River Arbey. “They went to serve directly with the Ukrainian army,” at the invitation of President Volodymyr Zelenskiy, he explains. His brother left Ukraine after eight months, with his head held high and with the doors open if he ever wanted to return, he adds. “They are not mercenaries, as they have been labeled; mercenaries are hired by private companies.”

In the video released by the FSB, both men identify themselves as members of the Carpathian Sich 49th Infantry Battalion. The soldiers of the 49th battalion, many of them foreigners, have fought on the toughest fronts. At times, the unit has been severely depleted, particularly during winter at the end of last year. Some of its fighters have left the front lines in the face of the harshness of the war. “For a long time, it was the flagship battalion where Colombians fought, alongside the international legion,” Colombian journalist Catalina Gómez Ángel, who has been deployed for long periods as a war correspondent in Ukraine, says by telephone. She is currently working on a documentary about Colombians at the front, most of whom are former soldiers who worked in security. “They tend to be relatively young people; many of them, in addition to money, miss the military life,” she says about their motivations.

The Colombian presence has been noticeable for some time. With the Ukrainian ranks decimated by the rigors of war these combatants, hardened in one of the longest armed conflicts in the world, are welcomed with open arms. With some 250,000 troops, Colombia has the second-largest army in Latin America, after Brazil. More than 10,000 soldiers retire every year. After President Zelenskiy’s explicit invitation last February, they have been recruited through WhatsApp groups of ex-military personnel and through videos on social networks. They arrive in Ukraine on their own, like other Latin Americans. They enter from Poland, cross by land into Ukraine, whose airspace is closed, pass through a recruitment center and are deployed to a front in the east. That explains the striking Warsaw-Madrid-Caracas-Bogotá-Cali itinerary that Medina and Ante bought for their return, without realizing that showing up at Maiquetía in Ukrainian military uniform would expose them.

Although the Colombian Foreign Ministry has not made a public statement regarding the two former soldiers presumably extradited to Russia by Venezuela, it has raised the alarm regarding international combatants in general. Neither Ukraine nor Colombia offer concrete figures on how many Colombians are fighting in the war, but the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has acknowledged that at least 50 have died in the last two years. It has also recently reiterated that “the Colombian government does not promote or facilitate the involvement of Colombian citizens in the Ukrainian army. These personal decisions are completely voluntary and individual.” The ambassador to the United Kingdom, former senator Roy Barreras, even warned in June that “those who leave with the hope of earning money for their families are dropping dead like flies. What they are paid is not even enough for the repatriation of their corpses. So they are being used as cannon fodder.”

International law is ambiguous about the legality of foreign participation such as that of the Colombians in a war like Ukraine. The Colombian Foreign Ministry and the Ministry of Defense have just submitted a bill to the Congress of the Republic seeking approval of the International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries. In other words, they are seeking a formal ban on mercenaryism in Colombia, although it is not entirely clear that those who go to Ukraine fall into that category, since they fight in a regular army and receive payments and benefits similar to those of Ukrainian citizens. Kyiv considers them legal combatants. Russian legislation, for its part, considers mercenaries illegal, but at the same time it is one of the countries that most relies on private companies and foreign combatants.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.