What they don’t usually tell you about Hitler: He was chronically idle and hated cats

A short but illuminating book by veteran French historian Claude Quétel examines the truths and myths surrounding the Nazi leader

It is no longer necessary to read Ian Kershaw’s almost 2,000-page biography of Adolf Hitler to form an opinion on the Führer’s character. Now, a short book of just 170 pages does the job, delving into the personality of the Nazi leader and giving us the tools to understand who he really was. Hitler, truths and myths asks 20 questions about whether he was crazy and had an unhappy childhood to whether he was impotent and what he knew about the atomic bomb. The answers cover just about everything you ever wanted to know about Hitler and didn’t know who to ask.

The book is the work of Claude Quétel, a veteran French historian, author of numerous titles, including a history of syphilis, others on psychiatry and madness, and several related to World War II and Nazism: La Seconde Guerre mondiale, Femmes dans la guerre 1939-1945, Tout sur Mein Kampf and even Le Débarquement pour les Nuls. It should be noted that from 1992 to 2005, Quétel was scientific director at the Caen Memorial, the museum dedicated to commemorating the Normandy landings.

Quétel begins by recalling everything that has been written about Hitler, including the exhaustive biographies available to us — the latest being Volker Ulrich’s 2,000-page tome — and asks himself what is left to say.

In answer to that question, he writes, “This book sets out to examine what is problematic in a biography of Hitler.” He is not reviewing Nazism, the genocide of the Jews or total war but attempting to reveal what made Hitler tick, and in doing so he debunks some preconceived notions.

Quétel bases his conclusions on the memoirs and diaries of Speer, Goebbels, Traudl Junge, Von Manstein, Von Papn and Riefenstahl, among others, and points out that when we examine Hitler we are left wondering how such a mediocre individual who was “chronically idle” and “of little more than average intelligence, borderline in terms of mental health, was able to become the absolute master of the Third Reich and push the world towards the most atrocious of conflicts.” He also points out that, in 1920, there were already those who recognized that German militarism was still strong and had the potential to become stronger: all that was needed was the right circumstance and man to pull the trigger.

Regarding whether Hitler had a happy childhood, Quétel recalls that his father, Alois, was relatively old at 62, and that his mother, Klara, 29, was the governess of the children of Alois’ second marriage and also his lover — a situation curiously similar to that of Lawrence of Arabia.

Alois and Klara married in 1885 with special permission as they were second cousins. They were not poor and apparently Hitler’s father, although certainly not at all affectionate, was no more authoritarian than usual for the time. His mother, meanwhile, made up for any lack of fatherly attention by being devoted to her son.

At school, Hitler was gifted but stubborn and had a hard time controlling himself. His father would have liked to have had a son who was a civil servant but Hitler insisted on being a painter, which — if this had turned out to be the case — would have been better for everyone. Alois died at the age of 65 of a pulmonary hemorrhage, and from then on Hitler was a fairly happy boy, enjoying “the best years of my life,” as he wrote in Mein Kampf — spoiled by his mother and allowed to laze around.

Hitler’s failure to pass the entrance exam to get into the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and the death of his mother from breast cancer mark the end of his childhood and early youth. Quétel concludes that Hitler’s childhood cannot be described as unhappy. Nor can his family be described as toxic. What was crucial to Hitler’s future was “the laziness and propensity to dream of a child who very soon lost control of reality.”

Was Hitler always antisemitic? The author answers this by examining the miserable time he spent in Vienna, going “from sordid café to sordid café”, and embracing the völkisch, nationalist, and racist movement. It was then that “this individual empty of culture and knowledge and of a limited intelligence” — basically a social misfit — fed off the “poisonous phantasmagoria” of antisemitism. “Except for his teenage years in Linz, Hitler was always antisemitic, with successive layers becoming thicker and more irrevocable.”

A fascinating chapter is one that dwells on whether Hitler was a hero of the First World War, based largely on Thomas Weber’s research. Weber concludes that, as a geifreiter, equivalent to a lance-corporal, Hitler enjoyed a privileged position as a staff courier. As such, he was able to dodge the worst of the slaughter and be around those handing out medals; he won the Iron Cross first class. Quétel believes that Hitler was not promoted despite being a decorated soldier because to have been so he would have had to abandon his relatively safe position and participate directly in the fighting. In which case, he would probably have died, and no questions about his character would need to be asked.

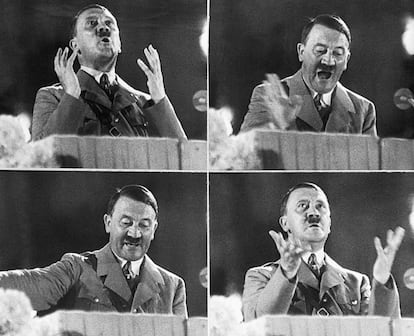

Was Hitler’s eloquence and political capital extraordinary? Quétel points out that the Nazi leader prepared everything meticulously, with all gestures rehearsed, the most striking being the Nazi salute, not to mention other stage tricks. He believes that part of the secret of his “orgasmic rhetoric” in which he “mated with the masses” as a “sublimation of his failed sexuality” was that he spoke to audiences that were eager to hear what he had to say, and he reckons that the French would have quickly tired of Hitler’s rhetoric.

According to Quétel, Hitler’s rise to power was irresistible and resistible at once. He compares it to that of Bertolt Brecht’s mobster Arturo Ui. He points out that his charisma did not work on everyone and that people like Sebastian Haffner had him down as a nobody “with a pimp’s hairstyle, shoddy elegance” and “epileptic gestures.” Quétel refers to what Haffner said of the majority of those cheering him at the Berlin Sportpalast in 1930 — that they probably would have avoided asking a man like that for a light on the street.

Of Hitler’s culture and knowledge, Quétel considers that it was only skin deep and that his obsession with monologue was related to his insecurity and inability to hold a normal conversation due to lack of arguments. “He lived in fear of being caught in the act of amateurism,” Quétel writes.

Quétel contests Timothy W. Ryback’s assertions that Hitler was an avid reader and considers his library “circumstantial.” As to whether he was a workaholic, Quétel says he absolutely was not. He was too lazy to learn English. He didn’t drive. And he constantly improvised. On the controversial issue of whether the Holocaust was carried out on his specific orders or whether those around him were more responsible, Quétel says that the debate is now over and that “the functionalism of a Final Solution, with stages closely linked to the circumstances of the war, does not contradict the intentionalism of a Hitler who always made the extermination of the Jews his program, his supreme mission.”

On whether Hitler had a private life, Quétel agrees with Kershaw, writing “if you take away what was political in him, there is not much left, if anything.” The evenings he organized at the Berghof, his bourgeois alpine refuge, were considered deadly boring with stacks of cakes served and no alcohol, although sometimes he skillfully imitated Ribbentrop, Goebbels, and Goering.

Hitler did like movies, including Ben Hur, which he watched with Rudolf Hess, no doubt both of them siding with Messalla in the chariot race. He did not, however, like cats, arguing they killed birds. He much preferred dogs, although if you think about how he ended up treating his dog Blondi — poisoning her to test cyanide capsules — it makes you wonder at his capacity for affection. All the same, it is said that in the Führerbunker, Hitler cried more for Blondi than for Eva Braun.

Regarding the much-discussed question of whether Hitler was impotent, Quétel points out that it is almost certain that Hitler left Vienna at the age of 24 “without having had a hint of sexual intercourse with a woman, or for that matter, with a man”; however, he liked cabaret shows featuring scantily clad girls. Later, he had platonic relationships with middle-aged women who protected him. It is believed that he fell in love with his step-niece Angela Raubal, but Quétel doubts there was any sex. As for Eva Braun, Quétel refers to the testimony of the laundry manager at the Berghof retreat, who always examined the sheets before washing and claimed there was no evidence of intercourse. Quétel concludes that Hitler only loved himself.

Quétel reckons that Hitler had no artistic talent. He also states that he did not improve working conditions in Germany — the working class lost all its rights, and that is without taking into account those who ended up in Russia. Women also lost their position in society. Rosenberg said that women had to be “emancipated from emancipation.” Quétel also relates how Hitler had to bow to the German churches, which he detested, regarding Nazi euthanasia; and despite everything that has been written, he was only attacked in person twice — in the Munich beer hall on November 8, 1939, and in the Stauffenberg plot on July 20, 1944.

Why the British tried to kill Rommel and managed to kill Heydrich but did not attempt to kill Hitler may have had something to do with the fact he was a lousy strategist, and therefore it suited the Allies that he remained in charge. His big mistakes include Russia and Dunkirk: it is possible that regarding Dunkirk he prioritized political strategy — not giving too much glory to his generals — over military strategy. In any case, Quétel acknowledges that Germany could not have won the war.

Was Hitler crazy? Well, crazy no, but he lived in a parallel reality, rejecting the world as it was — something that happens to many of us every morning without it leading us to invade Poland. There was also his hysteria, evident when SS General Felix Steiner’s army did not manage to liberate besieged Berlin, which indicated a certain mental insanity. And he was on a lot of drugs by the end. Quétel concludes he had a “paranoid personality,” though he undoubtedly knew what he was doing. Regarding the atomic bomb, the book points out that, fortunately, it was not explained to him properly.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.