‘Mein Kampf’: a century of radioactive potential

The rhetoric and concepts in Hitler’s 1925 collection of essays continue to resonate in an increasingly polarized world

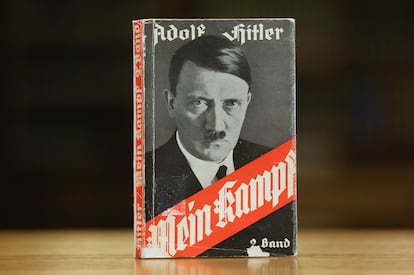

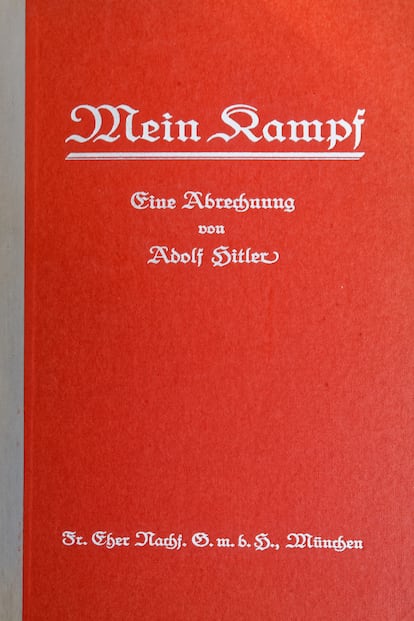

The book has the power to terrify a century later. The red cover. The Gothic letters. The title: Mein Kampf. Eine Abrechnung (My Struggle. A settling of scores). The author: Adolf Hitler. His photo is inside, not on the cover as in later editions. He appears in profile, with a dark background, like a character in an expressionist film – perhaps Fritz Lang’s thriller M. First volume, first edition: July 18, 1925. It’s just a book but it’s also something else. The Nazi manifesto. A handbook. A bible, even. Perhaps the most influential piece of writing of the 20th century. The one that would sell 12 million copies in Germany alone, the one that the Nazi regime gave to newlyweds and the one that Germans burned, buried in the garden, or hid in the attic after the war. The one that this journalist now has before him. He touches it carefully, turns a few pages and says:

–It seems radioactive.

We are at the Institut für Zeitgeschichte (IfZ), the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich, which in 2016 published the critical edition of Mein Kampf. Daniel Schlögl, head of the IfZ library, has brought a copy which the library received as a donation: “People inherit it and don’t want to throw it away, but they don’t want to have it at home either. It’s awkward.” Radioactive, then? Historian Andreas Wirsching, director of the institute, answers:

–Precisely one of the objectives of critical editing was to put all this into perspective.

That is, to cool the incandescent object. To demystify it. The critical edition of the Institut für Zeitgeschichte, of which 119,000 copies have been sold, has succeeded. It was intended to offer the reader what is essentially a historical source, rather than the book in its raw form without the footnotes and comments necessary to understand it and put it in context. The project sought to defuse the risk that, when the copyright, owned by the Bavarian Ministry of Finance, was lifted and so too the ban on publication in Germany, editions designed to spread Hitler’s message without context or explanations would come out. So far, mission accomplished.

EL PAÍS visited some of the scenes of Hitler’s rise and interviewed those who have dedicated their lives to studying Nazism and its manifesto. For example, Munich, where the future dictator organized the Beerhall Putsch in November 1923, for which he was sentenced to five years; the prison where he served a small part of his sentence and wrote the first volume of Mein Kampf in Landsberg am Lech, 60 kilometers (37 miles) to the west; and Salzburg, on the other side of the border with Austria where he was born and raised. As Hitler says at the beginning of his writings: “I now think it’s lucky that fate gave me Braunau am Inn as my birthplace. For this small town is located on the border between the two German states, whose reunification seems, at least to us young people, the task to be undertaken by all possible means.”

Mein Kampf would seem now to be a product of the past that has little current relevance and that few read. A common idea is that it is unreadable due to the overloaded language, the repetitions and the wordiness. This explains why, although many had a copy, few actually got through it. It may seem to belong to the past, but in fact its message is more present than we might hope due to its twisted logic, hatred, conspiracism, racism and antisemitism, resentment and polarization. All of this resonates today.

“Potential parallels or analogies between Hitler’s National Socialist era on the one hand and our right-wing extremism on the other exist, I think,” says Wirsching in his office in the IfZ. “Although perhaps not so much in political language, which is more nuanced today. It must be said that the verbal violence was greater then, although we do not know what will happen with that in the future. Naturally, what is similar is the friend-enemy device; the target audience and the traitors. The target audience and the immigrants. It must be said that these are dichotomies reminiscent of the 1920s and 30s, but without that meaning Mein Kampf can be transferred to the present time.”

There are never-ending debates. One of them is whether Mein Kampf is central to understanding Nazism, or if there is no such thing and it is merely collateral. “In my opinion it is central,” Wirsching says. “I would say that studying Mein Kampf is very important for the understanding of the National Socialist regime. At the same time, there is a risk – that of Hitler-centrism, which tries to reduce everything to Hitler, which, of course, is completely wrong. The mobilization of German society would have taken place without Hitler. An excessive focus on Hitler, on Mein Kampf, responds to a widespread German narrative of exculpation, according to which it was the demon Hitler who seduced the Germans and then violently oppressed them, and according to which the Germans were the first victims of National Socialism, which in turn was something that came from outside. In fact, the opposite is the case: National Socialism was deeply rooted in 19th-century German history, and that, of course, is also imaginable without Hitler.”

Another unresolved debate is that of intentionality: was everything proposed in Mein Kampf? Or did Hitler improvise, radicalizing himself to the point of destroying Europe and devising the Holocaust? “Our research points out that the intentional elements of the National Socialist regime, which also go back to Hitler personally, should not be underestimated,” says Wirsching. The war of extermination in Eastern Europe in pursuit of “living space”? That was in Mein Kampf. Forced sterilizations? Also. The destruction of communists, social democrats and trade unionists? All in the book, along with racism and antisemitism, although Mein Kampf did not explicitly propose the murder of millions of Jews in Europe. “But the logic behind it, which is the logic of extermination, can be found in Mein Kampf,” Wirsching points out.

The Landsberg prison in which Hitler wrote part of Mein Kampf is still operational. Next door, there is a cemetery where Nazi war criminals who were executed after the war were buried. On the outskirts there was a concentration camp. Gabriele Triebel, a member of parliament in Bavaria for the Greens and president of the European Holocaust Memorial Foundation, grew up here. He says that, until some time ago, this story was hardly talked about. “Like everywhere, there was a culture of silence, and it was not until the 1980s that people began to speak out thanks to the involvement of civil society,” he says. When asked if he has read Mein Kampf, he replies, “No, and I don’t want to.” If you want to be informed, there are books to read and memorials to visit, without the need to “immerse yourself in Hitler’s abstruse and sick mental world.”

Germany is tiptoeing around the centenary of Mein Kampf, perhaps to avoid the fetishisation of the author and his work. Similarly, the location of Hitler’s bunker in Berlin is marked by nothing more than a discreet panel. Among the specialists consulted for this report, some had not even realized that the anniversary was approaching: the date itself means nothing to them. Nor have the bookstores been filled with news on the subject.

In France, Olivier Mannoni, translator of Historiciser le mal (Historicizing Evil), the French version of the critical edition of the IfZ, has published Brown flow. How Fascism Floods Our Language. Citing “Hitler’s chaotic language in Mein Kampf [and] Trump’s on his personal network Truth Social,” Mannoni warns that “the disaggregation of language allows for manipulation. A language whose syntax, grammar and orthography are massacred can no longer be a tool for rational reflection.”

After a train journey from Munich to Salzburg, Othmar Plöckinger, a specialist and member of the team that produced the critical edition as well as author of Geschichte eines Buches: Mein Kampf, 1922-1945), a reference volume, waits for us at the Café Mozart. Plöckinger grew up near Braunau. He belongs to the generation that revealed former Austrian President Kurt Waldheim’s Nazi past, and he has been focusing on Mein Kampf for decades. He explains that the book “has haunted him for 35 years. I’ve always read it in single chapters,” he says. “In total I will have read it 20 or 30 times, but from beginning to end, never.”

Decades of research led Plöckinger to question some of the myths surrounding the book. One is that it is illegible. Yes, it is redundant, and evidently it is not written in the style of prestigious literature or essays of the time, the historian observes, but it must be understood as one of many books of the völkisch or the ethno-nationalist scene of the 1920s. “The others, thank God, are forgotten,” he says. “Hardly anyone complained at the time that it was illegible and some opponents even admitted that it was not badly written.”

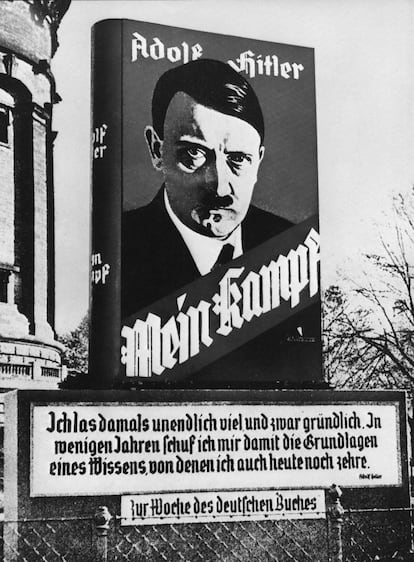

Another myth is that no one, or few, read Mein Kampf. But Plöckinger explains that before Hitler’s first electoral success in 1930 and his coming to power in 1933, Mein Kampf was read by the intellectual elite – and some like the philosopher Martin Heidegger even appreciated it – as well as by militants and sympathizers of his party, the NSDAP, and by the authorities who were monitoring the National Socialist agitator.

By 1933, it was already a mass phenomenon: people wanted to know what the ideology of the Nazis was now that they seemed to have come to stay. It was, however, read in waves. The first wave was that same year; the second in 1938 when readers were looking for clues about foreign policy. These are the peaks in demand that Plöckinger has observed in the records of the libraries of the time – a more reliable index sometimes than the sales of the book: whoever asks to borrow a book will generally read it.

Plöckinger is cautious when asked if it is the most influential book of the 20th century, or if it’s just that its author was one of the most influential characters of that period. “The book would have been insignificant if Hitler had not risen to be the leader of the nationalists and the Third Reich,” he says. And he explains that, in reality, it was not that it was an excessively original book for the völkisch and antisemitic culture of the era. Meanwhile, Wirsching believes that Hitler’s influence came more from his speeches, and points out: “I would say that, as a writer, Lenin was much more influential than Hitler.”

In the conversation in Salzburg, Plöckinger is wary of comparisons with the present: “There are many unpleasant things, many things that must be categorically rejected and yet cannot be compared to Hitler,” he says, adding that Mein Kampf has always been an object of study and research. Almost a decade after the publication of the critical edition, it already belongs to the scientific field, “and that’s where it has to stay,” he says.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.