The Nazi past that parents never wanted to talk to their children about

Hans Gräser, a 79-year-old German, discovered documents revealing the family’s ties to Hitler’s regime while clearing out his parents’ house. He’s not the only one to whom this has happened

The accepted silence within many German families after World War II has marked the society of a country that had to learn to live with its history. How can one explain to one’s children the terrible crimes committed during the Nazi era? The Mitläufer, as the Germans who followed the Nazi tide without resistance are called, represented the vast majority of the German people.

After the war, no one wanted to ask the question of what would have happened if they hadn’t let themselves be led by Nazism. Parents didn’t talk to their children, but rather to their grandchildren. However, even now, 80 years after the end of World War II, it’s difficult to talk about it, although no one doubts that without those millions of Mitläufer, neither Hitler nor his followers would have been capable of committing a genocide — around six million Jews died during the Holocaust — of such magnitude.

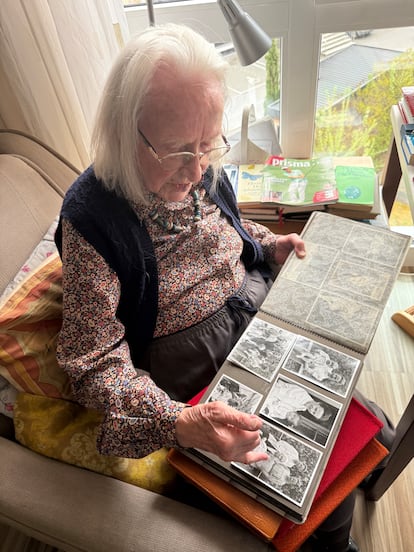

The issue resurfaces when, while clearing out a grandparent’s or parents’ apartment, families discover documents hidden at the bottom of a closet. In Hans Gräser’s case, he was aware of his father’s past in the SS, but not much more. That’s why he couldn’t help but be surprised to find a series of documents he hadn’t known about when his 101-year-old mother moved into a nursing home late last year, and their home in Heidelberg had to be vacated.

“I’d never seen these documents before. Not even the SS membership card, nor the denazification report…” he explains at home, leafing through the papers scattered on a table. Among them are, for example, the Ahnenpass, which documented his Aryan ancestry, and the War Merit Cross signed by the Führer.

“I learned then that he had been a member of the Nazi Party,” he says, referring to what he found in one of his father’s desk drawers. “I knew he was in Riga [Latvia]. Also that he was a judge at the Regional Court. But my father didn’t tell me what he did in Riga during World War II. That’s what they always say; that fathers didn’t talk to their children.”

Gräser, 79, is a historian specializing in the medieval period. It was difficult for him to imagine that his father was in Riga from 1941 to 1944 as part of the Nazi machine and never spoke to him about it. Mass executions such as the Rumbula Massacre, where nearly 25,000 Jews were killed, took place in that area. So, when he discovered that his father left the Reiter-SS (cavalry units) in 1939 and joined the Wehrmacht, as the armed forces of Nazi Germany were known, he didn’t understand why he hid it.

“The SS was always considered an elite. And in that sense, he may have said he didn’t want anything to do with the Nazi Party, which he found too vulgar,” Gräser speculates about the motives of his father, who died in 2009 aged 98 and never spoke about it.

“It seems like he only dealt with civilian matters. But of course, everyone there, even if they didn’t shoot, had to know what was going on.” For Gräser, it’s “difficult” to confront this past. How do you ask a father if he saw or was involved in any of those terrible crimes?

He occasionally spoke with his mother about that period. “But I’ve always been surprised by how naive she is,” he admits. “My mother, who didn’t learn about the crimes committed during the Third Reich until the end, had no interest in the subject and completely suppressed it.”

His mother, Margarethe Gräser, now lives in a nursing home in Weinheim, where her daughter resides. She was 22 when the war ended and was pregnant with her first child, Hans, whom she named after her husband because in September 1945 she didn’t know if he was still alive. The child was the product of the last leave the soldiers received, at Christmas 1944, a time they took advantage of to get married. “Almost all my schoolmates were born in September, like me,” Hans recalls, as a postwar curiosity.

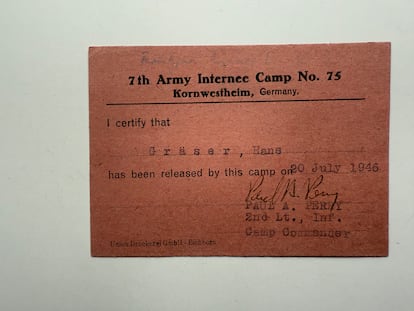

“The first Christmas after the war was the first time he was allowed to write a letter from prison,” explains Margarethe, sitting in her room at the residence. “That’s when we knew for sure he was alive and in American captivity,” she adds. From that moment on, her husband, who was in a special camp for high-ranking Nazi officials, was allowed to write one letter a month until his release in July 1946. The letters arrived with traces of powder the Americans used to check for hidden messages.

At that time, she had moved with her family to her grandmother’s old house in the center of Heidelberg, after the Americans occupied their home in Tauberbischofsheim. “They weren’t interested in our apartment in Heidelberg because it was very old and there was no central heating,” she recalls.

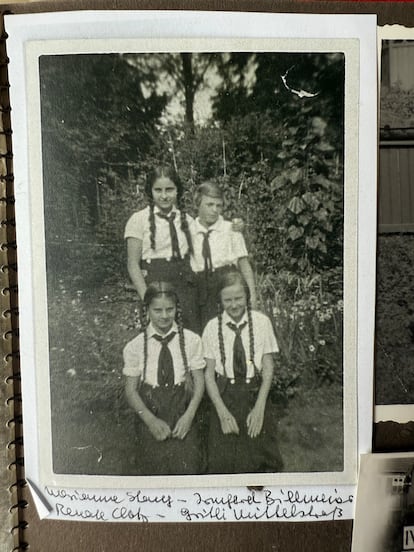

It’s hard for her to go back in time. She was a child when Hitler came to power in 1933. She recalls her time in the female branch of the Hitler Youth, whose membership became mandatory as of 1936. “I liked being part of a group of so many girls because I only had brothers. I liked singing with them, playing sports, and things like that. The truth is, I experienced that time in a positive way.”

Afterward, she was in the compulsory Reich Labor Service (RAD), where young women helped mainly with livestock and field work. She remembers little of those years, but she does remember that she was fortunate to be in peaceful areas. She also doesn’t know how she found out the war had ended, and claims that she didn’t learn “about the atrocities of the war” until it was over. She struggles to remember. “It’s been a long time,” she excuses herself.

“Somehow, we didn’t want to believe it. My husband probably knew more about it,” she admits. “Germany’s flourishing under Nazism, so to speak, was seen as a good thing compared to the previous era, when Germany was going through a very bad time. We didn’t know anything about the crimes that were committed. Those who lived through it were, I think, very reserved and cautious when it came to talking about it. And in the newspapers, of course, only good things were published.”

While many Germans hid their Nazi past after the war, the Gräser family was always aware of theirs. “He talked a little about his time in Berlin and Riga,” his widow says. “They were more formal things, what he did as a lawyer. He wasn’t very interested in politics. As a civil servant, he had to join a National Socialist organization and joined the SS,” she confesses.

His family read his experiences of that time in a memoir he wrote after his retirement. In the 200-page memoir, he recalls, for example, how he heard Hitler speak for the first time at a rally in Karlsruhe in 1932. “The content made little impression on me; it was dominated by crude polemics, but I witnessed the evocative power with which the audience was inflamed,” he wrote.

In 1938, he moved to Berlin. “The SS had special duties in Berlin. At least half of the service consisted of forming an honor guard at events in which the Führer participated, on watch, at parades, and the like,” he wrote. “Of course, in the autumn of 1938, I had to travel with my unit to the party congress in Nuremberg to march before the Führer,” Hans Gräser Sr. recounted.

Berlin also experienced Kristallnacht, the event known as the Night of Broken Glass, which took place on November 9–10, 1938, when thousands of Jewish businesses, synagogues, and homes were attacked by the SS, and nearly 100 Jews were murdered.

His appointment as a judge at the Berlin Regional Court came the following year, almost at the same time as his conscription, so he never actually held the position in the German capital. Upon joining the Wehrmacht, he left the SS, where he had risen to the rank of Rottenführer (section leader).

He lived through the surrender of Warsaw, fought in the Battle of France, and, after being wounded, was assigned in 1941 to the legal department at the Reichskommissariat Ostland office in Riga, where, according to his own account, he handled all non-criminal matters. In the final months of the war, he was wounded by shrapnel on the Eastern Front. These injuries probably saved his life, as he was evacuated to western Germany.

Along with these memoirs, which omit any mention of crimes committed by the Nazis, his son now also has the document his father included in the denazification report required by the Allies for his release. In it, he describes the charges he faced and his whereabouts until his arrest on May 9, 1945, and asks to be classified as a Mitläufer. He worked as a gardener at a cemetery in Heidelberg until he returned to the judiciary in 1949.

This appointment led to his name appearing years later in the so-called Brown Book, in which the German Democratic Republic (GDR) denounced nearly 1,800 business leaders, politicians, Bundeswehr generals and admirals, and high-ranking officials for their real or alleged ties to the Nazi regime. The West German federal government dismissed the book as a “work of communist propaganda.” However, Hans Gräser, upon seeing his name, offered early retirement, but his superiors saw no reason for his resignation and he remained in his post.

How much of his story did he leave out? It’s hard to know. His family now wants to request all available documents from the German Federal Archives to see if what is contained there is the same as what they already know, or if there’s more to it. They’re among the Germans who want to know. Not all of them do.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.