How Nazi propaganda dehumanized Jews to facilitate the Holocaust

A new study of speeches, pamphlets and articles from the period shows how German fascism denied Jewish people humanity to fuel hate and justify genocide.

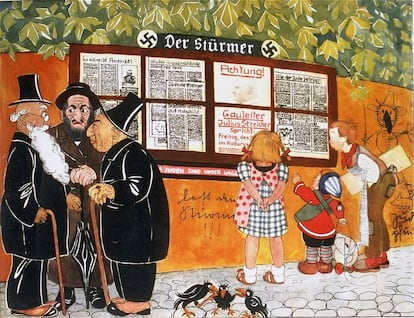

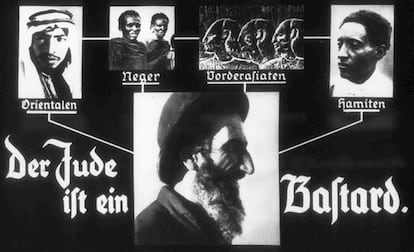

Rats, lice, cockroaches, foxes, vultures – these are just some of the animals the Nazis used to deride and dehumanize Jews. They used words too. In a new linguistic analysis of dozens of Nazi speeches, articles, pamphlets and posters, researchers show how this process of anti-Semetic dehumanization, which began before the Nazis took power and helped fuel the party’s popularity, was modulated to justify atrocity: in the years before the Holocaust, Jews were represented as a being incapable of human feeling. Coinciding with the Nazis’ early efforts to exterminate them, European Jews were depicted as agents of evil, as demons, as a nefarious cabal scheming up threats. The consequence, whether intentional or not, was to overcome the moral barriers to their mass elimination. By the end of the war, the Third Reich had systematically murdered six million Jews.

In a new study from Stanford University, the University of California, and Tel Aviv University, researchers have turned to psycholinguistic analysis to quantify the “mental state language” of Nazi propaganda between 1927 and 1945, and have published their findings and methods in the paper, “Dehumanization and mass violence: A study of mental state language in Nazi propaganda (1927–1945).” Stanford University’s Alexander P. Landry, a co-author of the study, explains: “Mental state terms are those related to the ability to feel sensations and emotions or, on the other hand, the ability to have complex thoughts, and to plan and act intentionally, that is, to have agency.” The basic theory underlining the study postulates that recognizing another person’s capacity to feel promotes moral concern and encourages us to prevent harm towards others. And conversely, when we deny a person’s ability to feel – what the authors call “mind denial” – we justify abuse and violence.

The analysis of Nazi propaganda, published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal PLOS One, confirms through quantitative data analysis what most people already knew: that the Nazis dehumanized Jewish people. During the period under study, the use of terms invoking emotions and agency remained at high levels, but increased in the lead-up to the Holocaust. “We observed that Jews were progressively denied the capacity for fundamentally human mental experiences in the run-up to the Holocaust, suggesting that they were increasingly denied moral consideration during this period,” Landry says. This progressive denial would have facilitated the systematic atrocities carried out against the Jewish population. “However, after the onset of the Holocaust, Jews were credited with increasing levels of agency. This may reflect an effort by Nazi propagandists to demonize Jews, portraying them as intentionally malevolent agents of evil, in order to justify the violence inflicted on them,” Landry says.

Increasing allusions to Jewish agency in the early phase of the Holocaust are evidenced, the study shows, in the increasing use of terms relating to intentionality, such as “evil,” “infernal,” “plan” etc. Meanwhile, after the horrors of the Holocaust were well underway, the use of terms such as “mind,” “benevolence,” and “feeling” tend to decline. Of the sample of words selected by researchers for the study, the term that declined the most in Nazi texts, beginning in the summer of 1941, was Liebe, German for “love.” In fact, it is during that same period that researchers identify a shift in the use of certain words over others. Although the Holocaust officially began in January 1942, when the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” was approved at the Wannsee conference in Berlin, mass murder and starvation had already been inflicted on communities in Eastern Europe beginning as early as the summer of 1941.

Theories of dehumanization maintain that denying a person or category of people the ability to feel serves to remove moral barriers to inflicting harm on fellow human beings. This is why Nazi propaganda, for example, frequently associated Jews and others deemed less-than-human by the Third Reich with vilified animals or infectious diseases. But, the authors of the study claim, the process is more complicated than that. “These patterns are consistent with claims that the Jews were subject to demonization, in which their capacity for sophisticated reasoning was perceived to coexist with a subhuman moral depravity,” the study’s conclusion reads.

Harriet Over, a researcher in psychology at the University of York, studies theories of dehumanization in cases of mass violence such as the Holocaust. Over says that the concept of dehumanization can refer to different dynamics. “Some researchers define it as treating humans in ways they should never be treated,” she says. “If that’s what we’re talking about, then of course the Nazis dehumanized the Jews.” But for some who study the phenomenon, dehumanization refers primarily to the use of derogatory metaphors, or the act of simply equating people with animals. “If we’re talking about that,” Over says, “then it’s also true that the Nazis dehumanized the Jews. Nazi propaganda is replete with references to Jews as vermin, rats or parasites.”

However, Over notes that there is another way dehumanization is often conceived, which essentially consists in seeing and defining another group as subhuman. Understood in this way, the assertion that the Nazis denied Jews their humanity is, according to Over, controversial: “I have argued, and so have others, that systems of terror can actually only be maintained if the victims are understood as human,” she explains. “To oppress an entire community of people, it is necessary to understand that they are human and to terrorize them into submission. Nazi propaganda often refers to the Jewish people in specific human terms. For example, describing them as ‘enemies,’ ‘criminals,’ and ‘traitors.’ These terms make sense when applied to humans, but seem out of place when applied to animals. Similarly, prominent tropes in Nazi propaganda refer to specific human states of mind that are supposedly typical of the Jewish people, for example, accusations that they are plotting to achieve world domination.” This view is consistent with some of Landry’s research findings.

In his book Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization, psychologist David Livingstone, the grandson of a German Jew and a professor at the University of New England in Maine, discusses the history of lynching in the United States. Of the 4,467 people killed by lynching during the period for which documented records exist (1883 to 1941), only 73 were white. With the exception of the occasional Native American, the rest of the victims were Black. In a lecture recently delivered by Livingstone at the University of Arizona, he explained what these executions were like. Thousands of people gathered from all over the region. Schools would close so that children could attend. Typically, the victim would be tortured and mutilated for hours before being executed. “How could people do such a thing?” professor Livingstone asks, and then suggests an answer: in his survey of newspaper article from the era, Livingstone notes how chroniclers of the spectacle tended to use adjectives like “monster incarnate,” “unnatural monster,” or, as the New York Sun wrote on one occasion, “the most inhuman monster known in these times.” More than animals, Black victims of lynching were considered monsters with both human and animal traits. And, notes Livingstone, this is also how Nazi propaganda portrayed Jews.

“David [Livingstone] has written a careful study showing that Nazi propaganda contains references to Jews as nonhuman animals (for example, rats and parasites), as well as criminals, enemies, and traitors. He uses this evidence to argue that the Nazis perceived Jews as both human and subhuman at the same time and, thus, portrayed them as horrible monsters,” Over says. And, she adds, stripping them of their status as human beings helped facilitate the Holocaust. However, as the British psychologist explained in an email to EL PAÍS, the process of dehumanization is not a necessary prerequisite for barbarism: “As Paul Bloom [a psychologist at the University of Toronto studying human nature and human cruelty] has argued, the claim that when we recognize ourselves as human, we tend to treat each other well, is a view that errs on the side of optimism. The reality may be much worse: there are certain kinds of harm that we reserve only for other humans.”

Livingstone maintains that “the Nazis really did regard the Jews as dangerous Untermensch (subhumans).” But he does not believe that this dehumanization was a simple and straightforward Nazi plan: “The Nazis’ dehumanization of the Jews was not a strategy to justify their extermination. Rather, it was the basis for their extermination,” he wrote in an email. And, he says, those ideas from over a century ago are not merely a thing of the past. “We are still creating [monsters],” Livingstone says. “We see it in European attitudes toward Muslim and African refugees, in the genocidal war in Ethiopia, in anti-Muslim propaganda in Myanmar, in Russian attitudes toward Ukrainians, in Hindu Islamophobia, and in American racism against Black people, to cite just a few examples.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.