The retired electrician who has revived cinema in a corner of Spain

Miguel Pérez, an amateur film buff, repairs projectors and other pieces of enormous cultural value, and displays them in a museum in the village of Veguellina de Órbigo, far away from the cultural centers of Spain

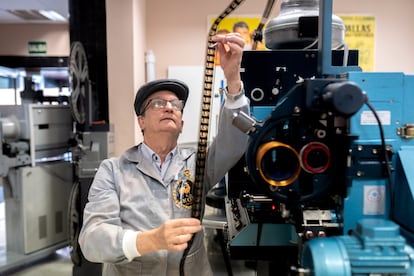

The ritual begins with a retired electrician – who used to work at a sugar factory in the Spanish province of León – donning a gray cap and a smock with the Italian title Operatore de la macchina (“machine operator”) scrolled across the front. The man sits in a chair with a cloth back – like those used by filmmakers – on which the phrase Trébol el proyeccionista (“Shamrock, the projectionist”) is written. He carefully selects a Pathé Baby projector, a relic from 1912, grabs its handle and turns it on to project – on a simple panel – the silent, comical antics of The Tramp, Charlie Chaplin’s famous character, in black-and-white. Only the clatter of the device interrupts the silence.

Miguel Pérez, known as Trébol or Trebolín (“shamrock”) to his friends, smiles with satisfaction. “Everything works here!” he exclaims, throwing open his arms as if he wants to encompass the entire film museum in Veguellina de Órbigo, a village of 2,000 people in the province of León. The structure is filled with centuries-old pieces that were purchased and fixed by Trébol. He’s loaned them to his town for the enjoyment of film buffs, as well as for curious locals and outsiders.

The small-framed Trébol, a 68-year-old native of León, enjoys showing off his collection. For three decades, he’s been applying the electromechanical knowledge he learned in the sugar beet industry to the cables, connections, lenses, motors and various components of the seventh art. He’s dedicated his time and money to acquiring all kinds of devices – some completely broken – to resurrect them with agile hands and tenacity. What began in his house in the town of Veguellina grew and grew – in volume, quality and value – until he agreed to an altruistic exchange with the City Council. He would be loaned a space that had fallen into disuse, with the purpose of creating a film museum. It was an unexpected project, considering Veguellina’s distance from the cultural centers of Spain.

The space features several rows of seats, around 100 projectors (of all sizes, origins and conditions), reels of film, as well as posters advertising historic movies such as The Ten Commandments (1956), A Night at the Opera (1935) and Cinema Paradiso (1988) and the latter’s main character, Totò, who so many lovers of the big screen identify with.

Trébol is the first to feel a connection with this character, who is depicted in the movie first as a young boy who’s fascinated with film, and later as an adult who has achieved success as a film director. Cinema Paradiso is Trébol’s favorite film and his most prized possession. He even has two versions of the Italian movie: the standard one and another with a director’s cut for collectors. Of course, he’s a bit of a Totò himself: he was 13 when he started out as an apprentice in an electromechanical workshop and 14 when he joined the Apolo Cinema, doing a bit of everything. He also worked at Gordóns – another local movie theater – back when his town used to have a film competition.

Today, there are no movie theaters left in Veguellina de Órbigo. Even in the nearby city of León – the provincial capital – there are hardly any left. The booming mining hub followed the same fade to black as the coal industry and the land: over the summer, the province was one of the hardest hit by forest fires, fueled by a lack of prevention, as well as the depopulation of rural areas

The sexagenarian laments the province’s decline. And he insists that – given the cruel passage of time – someone will have to manage and care for the cinematographic cultural treasure he has created in Veguellina.

Pérez preserves evidence of this cinematic wealth in the form of countless stacks of ticket stubs from past decades, with titles unknown to youngsters. However, visitors from the new generations are amazed when they see the operator perform a magic trick with the crank: they get to discover the adventures of Popeye the Sailor. He was delighted when a young film student who visited the museum returned some time later to tell him: “Thanks to your explanations, I got an A.”

His diverse and comprehensive collection has led to the creation of the Luna de Cortos International Short Film Festival and has attracted national and international visitors to the museum: a carousel of affectionate messages in the guestbook at the entrance proves it. “To my dear friend Miguel,” begins a note by someone from Calcutta, who thanks their Spanish friend for his teachings.

“[Collectors] from Madrid or Barcelona want to buy everything from me, but I want it all to stay here,” the owner of the materials emphasizes. Back in 2016, he received a medal from the Lumière Foundation for his dedication, teaching and knowledge. He has also given workshops on film at King Juan Carlos University in Madrid.

The guided tours he gives of the museum – which can last up to three hours – always include some skeptic who, upon seeing so much equipment, exclaims: “Junk!” However, they eventually end up withdrawing their comment, admitting that “This is marvelous!” Nothing is junk, Trébol reiterates, as he’s responsible for keeping everything in top condition. He’s even made homemade shutters, pulleys, shafts and step rollers for whenever a machine comes in that’s been dented or damaged, due to neglect or disuse. He has spent weeks and months of work on certain projectors, applying surgical precision.

“Nothing here is for sale!” the handyman exclaims. He often combs the markets to expand his display, and he often comes across an almost-unanimous truth: “Nobody gives anything away; everything [has to be] purchased. And sometimes, there are missing parts that no longer exist and cannot be manufactured.” The problems are common: the motor is fried, the sound doesn’t work, the roller has burned out, the capacitors have rotted, the system was poorly assembled…

Trébol works for himself and the town of Veguellina. But he also fulfills orders from other, less adept repair enthusiasts who desperately turn to him, looking for solutions or missing components. For instance, a wealthy Madrid collector discovered the curator through his press appearances: he managed to track him down after calling the town’s bars and asking for this magician, who’s capable of bringing dead engines back to life. “Charge me whatever you want!” the client begged, asking him to repair two broken projectors. “I charged him a fair price,” this cinematic goldsmith recalls. When he asked for his fee, he was told: “I would have paid double.” But the resident of the province of León replied that he “isn’t a thief.”

Retirement has allowed him to fully focus on his passion, which – in the past – was somewhat shelved when the sugar season arrived and beets were more important than feature films. “During the pandemic, I had breakfast, lunch and dinner with a projector,” the gentleman summarizes, with energy and enthusiasm.

“This toy is from 1911,” Trébol murmurs, as he caresses one of his beloved Pathé Baby projectors. It will subsequently show sequences of a Paris that’s unrecognizable today: recreations of the Stations of the Cross, or the first cars driving through the city. In the museum, there are also informational posters – such as one that reads “Smoking is prohibited” – that are displayed before the session, as well as advertisements for local restaurants, motorcycle shops, or furniture stores that once existed in the town. Images from another artistic and socioeconomic era, where people like Trébol made the country dream, even as it was deprived of movie theaters.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.