Pierre Boulle: The spy who invented ‘Planet of the Apes,’ a world with intelligent gorillas and humans with lazy brains

The French writer and soldier, who also penned ‘The Bridge over the River Kwai,’ didn’t think that his portrait of a society in ruins would work well on screen. We are into the 10th film in the franchise

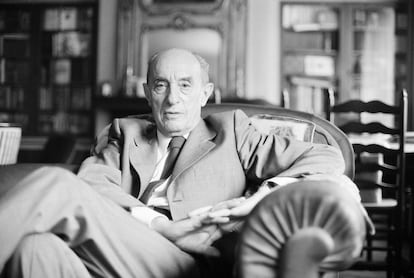

Pierre Boulle is one of the most translated French authors in the world. He is also one of the most forgotten. Author of 40 novels and books of short stories, this French engineer and soldier became a writer after returning from World War II, where he fought with the rank of lieutenant in the Indochina Peninsula, and later as a secret agent for the British Army. Upon returning to his country he wrote The Bridge over the River Kwai, a story about a group of prisoners of war in Burma forced by Japanese troops to build a railway crossing, which made history when David Lean took it to the silver screen in 1957. Nobody has forgotten that whistled tune.

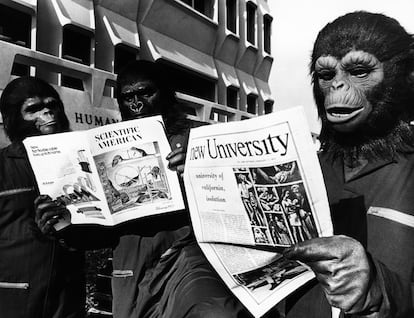

Boulle’s fame was amplified when the Frenchman published Planet of the Apes, a parable about a world dominated by primates, a story in the wake of Orwellian farces that gave rise to an inextinguishable franchise, starting with the adaptation which Frank Schaffner directed in 1968 with Charlton Heston as the lead. On Friday, the saga returns to movie theaters with Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, a new twist to Boulle’s story that, after some creative licenses in recent years, resumes the spirit of the original.

The French writer wrote a philosophical reflection during a time when humans were concerned about the future of civilization after two world wars and the disastrous culmination of the atomic bomb, which had reduced human beings to the status of wild animals. “The relativity of good and evil is the theme that I have tried to illustrate in most of my books,” Boulle admitted before he died in 1994. His experience on the war front was “the spiritual substance” of his work. During the postwar period, he asserted that “the absurd had become a form of logic.”

It has been written that this tireless walker had the idea for the book while observing the apes at the Jardin des Plantes zoo in Paris during one of his walks. But the author pointed to another source of inspiration: discovering the French capital’s Stock Exchange brokers in action. “One cannot imagine for a second that these beings are homo sapiens. It is unimaginable that they act using reason. It is an animal behavior in which intelligence has no place,” he said in the program Lectures pour tous, on French television, in 1963. He added that his analysis was also useful for “other collective manifestations.” For political party rallies. For the arbitrary verdicts of the judicial system, such as the one that led him to be convicted of treason against the Vichy regime. And, without a doubt, for the fight between opposing clans that only generated destruction around them, obeying primary and random laws of domination.

The writer’s experience on the war front was “the spiritual substance” of his work. During the postwar period, he asserted that “the absurd had become a form of logic”

Thus he devised a future reality on the planet Soror (sister, in Latin), where human hegemony has been overthrown by primates, organized into castes—the gorillas are police soldiers; the orangutans, political and religious authorities; chimpanzees, teachers and scientists—and very gifted for technological innovation. If the hi-tech society imagined by Boulle was replaced in the film version by a semi-civilized world, it was only because Fox, on the verge of bankruptcy after the expense of Mankiewicz’s Cleopatra, didn’t have the money to make it a reality. “Monkeys and men have evolved in divergent ways, the former rising little by little to consciousness and the others stagnating in their animality,” Boulle wrote in his book. “A cerebral laziness has taken over us. No more books! Even detective novels have become too much of an intellectual drain.”

Born in Avignon in 1912, Boulle graduated as an engineer in Paris and accepted a job as a foreman on a rubber plantation in Malaysia. Mobilized by the French army in 1939, he enlisted in the Resistance two years later. He was educated in the art of slitting the throat of the enemy in the jungle together with the British intelligence services, and fought in China, Burma and Indochina, where he was detained by a French commander who, despite sympathizing with De Gaulle’s Free France, preferred remaining faithful, out of cowardice, to Marshal Pétain. That soldier may have inspired the character of Colonel Nicholson in The Bridge on the River Kwai, blinded by his sense of duty and empirical proof of the banality of evil. Boulle spent a year in prison in Hanoi and was sentenced to hard labor in a rigged trial. That was his experience on the front: an absurd pantomime led by ideological weather vanes at the service of the side they sensed to be the winner, which they obeyed like well-trained apes, without any sense of morality.

For Boulle, Planet of the Apes was one of his minor works, a mere satire on the self-destructive drive of the human species. The immense popularity of the book, which none of his other works managed to match, condemned him to an inferior stratum within French literature. Not a fan of the intellectual circles of Saint-Germain, where he never felt at ease, he lived like a hermit in the Parisian house of his sister and niece. Before he died, he told the latter—his heir and the first to read his manuscripts—that he hoped the world would not forget him, as if he was already aware of that possibility. He was right, although there is still hope: the rights to one of his novels, The Virtues of Hell, and to an unpublished script, The Planet of Men, a sequel rejected by Fox after the success of the first film, were acquired in March. The intention is to turn them into a movie and a series, respectively.

The portrait of a society in ruins contained in Planet of the Apes is an idea that has seduced successive generations, perhaps because it approached issues such as the climate crisis, animal rights, and genetic manipulation. Also xenophobia. “The racial barriers of old have been abolished and the discord they aroused have disappeared,” wrote Boulle in a passage that could have originated one of the subtexts of the successful 1968 film, with Heston in the starring role (“a perfect actor to catalyze the sense of guilt and self-hatred of certain Americans,” decreed Pauline Kael, always sharp). One of its screenwriters, Paul Dehn, persecuted by McCarthyism, claimed that he wrote some scenes inspired by the Watts riots during the summer of 1965, when the African-American population rebelled against segregation and police violence.

The book precociously dealt with issues such as the climate crisis, animal rights and xenophobia. “Racial barriers have been abolished and the discord they aroused have disappeared,” Boulle wrote

After the films of the 1970s, the uneven adaptation by Tim Burton in 2001 — despite everything, the most faithful to Boulle’s book — and a trilogy freely inspired by its postulates, the saga now reaches its 10th installment. The legacy of the French writer is of interest again in times of the Anthropocene, when the possibility of human extinction, which cinema has always liked to fantasize about, is no longer only in the realm of science fiction.

The funny thing is that, in his day, Boulle held that Planet of the Apes was a work unsuitable for cinema. Among other reasons, due to its complex narrative framework. In the book, two astronauts find themselves with a manuscript in outer space in which the events that the first film took up were narrated. In an unexpected final twist, Boulle reveals that these two characters, whom the reader had taken to be a man and a woman, were apes who laughed at the possibility that human intelligence existed. “Rational men? Men possessors of wisdom? No, this is not possible. The narrator has crossed the line.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.