How migrants in the United States are spending Christmas: ‘There is no reason to celebrate’

Separated couples, deported children, detained parents... The consequences of the Donald Trump administration’s anti-immigrant crackdown will mark the holiday season for thousands of families across the country

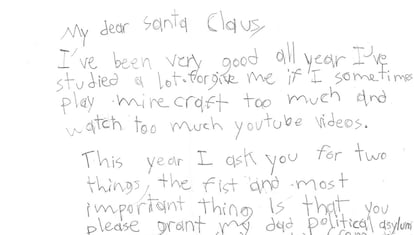

Pablo Casanella, the son of Cuban scientist and activist Oscar Casanella, wrote a letter to Santa Claus with two requests. “I’ve been very good all year. I’ve studied a lot. Forgive me if I sometimes play too much Minecraft and watch too much [sic] YouTube videos,” he told him, before asking for a Lego set. But that was his second request. The first, “and most important,” is a wish Casanella never wanted to read in his eight-year-old son’s Christmas letter: “Please grant my dad political asylum so we aren’t deported from the United States and so the Cuban military doesn’t arrest him, beat him, or imprison him.”

“My son’s letter made me feel incredibly sad and helpless,” Casanella says. “It’s impossible for me to stop my mind from ruminating every day, wondering what I can do to prevent my son and the rest of my family from feeling this anxiety, this insecurity. I think about what I should have done in the past to prevent this from happening, as if I could travel back in time or as if I had even the slightest control over the situation.”

These have been difficult times for the family. In 2022, they crossed the border into the United States when Pablo was four years old and his mother was pregnant with his brother. They had been targeted by the Cuban government ever since Casanella became a well-known activist in the country. For years, he was harassed, beaten, detained, and monitored by agents working for the Castro regime.

Now, in the United States, there’s no respite either: he still hasn’t received a response to his political asylum case. Pablo was born while his parents were under constant pressure from the Cuban government, and he’s growing up with the fear they’ll be arrested by U.S. government officials. “Since he was born, he’s constantly felt unsafe and sensed that our family is under threat,” his father says.

Some time ago, in the early morning hours, agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) knocked on the door of their Miami home. The family didn’t answer. “It traumatized us, leaving us afraid to leave the house for days.” This year, for Christmas Eve, the family will celebrate, as they always do, being together. They won’t take long trips, to “reduce the risk of being detained,” but they will gather with family, cook, and at some point, Casanella, a biochemist and former professor at the University of Havana, will pick up a guitar and start singing for everyone.

This year, he says, has brought a few good things. “The support I received from many friends and the Cuban exile community in the days before and after my political asylum hearing, and Pablo’s acceptance into the gifted student program, thanks to his talent and discipline,” he recounts.

But it has also been a difficult year. “The worst part is waiting for the judge’s response to my case. A wait that puts our lives on hold and creates the fear and suspicion that an unjust decision could put us within reach of the Cuban dictatorship’s intelligence services.”

Every time he gets behind the wheel of his car to go to work, navigating the impossible traffic on Miami’s avenues, Casanella feels unsafe. The fear of being the next person detained or deported persists. Especially now, with the Trump administration investing in a Christmas campaign to let the country’s migrants know they still have time to leave.

The Department of Homeland Security announced it will offer a $3,000 “exit bonus” through the end of December to all undocumented immigrants who leave the country voluntarily. Self-deportation “is the best gift an illegal alien can give themselves and their family this holiday season,” said the agency, adding that 1.9 million people have already voluntarily self-deported.

As the year comes to a close, the White House is boasting of several victories it believes it achieved in 2025. The administration has celebrated reducing encounters at the southern border by 99% since January, revoking more than 85,000 nonimmigrant visas, expelling over 605,000 people from the country, and detaining some 65,700 migrants, at least through the end of November.

Officials have said there will be no respite for migrants, not even during the Christmas season. Catholic bishops in Florida asked Trump to suspend “immigration enforcement activities over the Christmas holidays.” “Don’t be the Grinch who stole Christmas,” said the Archbishop of Miami, Thomas Wenski. The government rejected the request.

‘I have no other family here, only him, and he’s detained’

If she ever thought the family would be together for Christmas, she now knows that won’t be possible. A week ago, a judge informed Harold Martínez that he will be deported. There will be no Christmas Eve, no New Year’s dinner. Daniela, his partner, got rid of the tree and the garlands when she had to move into a much smaller place. Now she is the one working two jobs, caring for their baby, and paying the rent, the car, and the lawyer during the four months her husband has been held at the Krome detention center in Miami.

“I’m not going to do anything this December 24. I don’t have any other family here, just him, and he’s detained,” says Daniela. Martínez, 23, was stopped by the highway patrol in September. He didn’t have a license and was arrested. He left Cuba for Suriname in 2018 and crossed 12 countries before applying for entry to the U.S. through the CBP One app in 2021. Life had been calm. He earned a living working as a valet. The year 2025 brought him both his greatest joy and his worst misfortune: the birth of his son in January and his detention in September.

The baby was nine months old when Martínez entered Krome. “My son couldn’t even sit up, and now he can. Now he’s growing up, and he doesn’t even recognize me,” the father says, distraught, in a phone call from the detention center, where he has seen and experienced things he never imagined: mistreatment by officers, terrible food that has caused him to lose 9 kilos (20 pounds), doctors who turn a deaf ear to his suffering, and judges who reject his bond requests.

There are two questions Martínez has asked himself during this confinement. The first: “If they send me to another country, what will become of my family?” The second: “What did I do, what crime did I commit, to be where I am now?”

‘There is no reason to celebrate Christmas’

Almost every Christmas, Elmer Antonio Escobar González would fly from Michigan with his wife and two children to New York to be with his mother. In a photo they keep, they are seen in front of the giant tree that adorns the city at the Rockefeller Center. This year there will be no trips and no celebrations — only uncertainty for the family.

González, 33, is among about 20 Salvadorans accused of belonging to the MS-13 gang who were expelled by the Trump administration, in defiance of a judge’s order, along with more than 200 Venezuelans. Even now, neither his lawyers nor his family have heard anything about him. Although for months the government of El Salvador denied that González was in its custody, through the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) they learned that he had been transferred from El Salvador’s Terrorism Containment Center (CECOT) to the Santa Ana prison in the north of the Central American country.

The family has grown weary of demanding answers, and his lawyers have filed every kind of legal motion. They had hoped to receive some news about González before the end of the year, but no one has told them anything.

This December 24 there will be no stewed chicken on Christmas Eve, the family tradition. There will be no Christmas tree, nor a midnight exchange of gifts. González’s mother has been ill ever since she lost contact with her son, and the family is in mourning, as if they had buried someone. “My sister has lost the will to celebrate birthdays or holidays,” says his uncle, Josué Aguirre. “This year we don’t plan to do anything. There really is no reason to celebrate Christmas.”

‘A part of our lives is missing’

If there’s one thing Keily Chinchilla and her daughter, Allison Bustillo, love, it’s Christmas. Decorating the tree, putting up lights, wrapping presents. But this December, Chinchilla doesn’t feel like it. On a phone call with her daughter, now in Honduras, she tells her there is no Christmas without her. “She was the one who decorated my tree every year. That’s why I told her, ‘Honey, I don’t feel like decorating anymore.’ And she said, ‘No, Mommy, you should do it.’”

Last December 6 was the first time Bustillo celebrated a birthday away from her mother. She turned 21 in Honduras, despite having celebrated almost all her birthdays in the United States. She arrived when she was eight, went to school, and in February — on the day ICE agents abruptly entered her home in Charlotte, North Carolina, armed, and detained her in front of her three younger siblings — the young woman had just won a scholarship to study nursing.

After eight months in detention, she couldn’t take it anymore. She decided to self-deport. Now her mother, only because Bustillo asked her to, will prepare some Honduran tamales for herself and her children, along with some roasted meat.

“It won’t be easy to celebrate when a part of our lives is missing; nothing is the same anymore. This is my first Christmas without her,” says Chinchilla. By 2026, the mother hopes things will be different: “That next year will be better, that everything will turn out for the best. I would like to have my daughter back. That this whole nightmare will end, because this isn’t over yet; many people are still being separated from their families.”

‘The good things have outweighed the bad’

They weren’t able to spend Thanksgiving together. “That day left a bad taste — I looked at things, at people, and nothing interested me,” Alexandra Álvarez recalls. Today, however, she has reasons to celebrate. They won’t be going to the beach at midnight, as they used to do on Christmas Eve in Guayaquil, Ecuador, but in their Queens apartment they will do something simpler: she, her husband, and their little more than one-year-old baby will wear matching pajamas, have dinner with turkey or roast pork with stuffing — pork, chicken, sweet or savory dough, olives, and nuts. Then they’ll watch a movie.

She couldn’t ask for anything better after the long 44 days she spent fighting for the release of her husband, Manuel Mejías, who was detained by ICE at Federal Plaza in October and later held at Delaney Hall in New Jersey.

Álvarez, a 44-year-old teacher, still remembers the day her husband called to tell her he wouldn’t be coming home with her and their baby, who was about 11 months old at the time. “He said, ‘Honey, I’ve been detained.’ It was incredibly tense and confusing — I was desperate to figure out what to do.” After searching everywhere, she found help at Saint Peter’s Church in Manhattan and from Father Fabián, who has become a benefactor to migrants in the city.

It was the church that provided the remaining money needed to pay the $5,000 lawyer’s fee and a similar amount for bail. On December 2, “the judge determined that Manuel was not a danger to society,” Álvarez says. “My sadness was that my daughter was turning one on December 5 without him.” But Mejías landed in New York at 11:50 p.m. the night before, just in time to celebrate.

“The good things have outweighed the bad,” Álvarez says. “It was horrible when my husband wasn’t around. I felt very unstable, very insecure. As if I’d been stripped of a life. Being able to be together again is a blessing.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.