The Cuban migrant on hunger strike at Alligator Alcatraz: ‘It’s up to them to decide whether I live or die’

Pedro Lorenzo Concepción has been in the controversial Florida detention center since July 9. He decided to stop eating nine days ago to protest his detention and that of many others like him

Pedro Lorenzo Concepción’s voice seems to be sinking, shipwrecked among the vast wetlands populated by mosquitoes, pythons and alligators that inhabit the Everglades. He picks up the phone from Alligator Alcatraz itself, the feared migrant detention center that the Republicans built in Florida’s backyard. Asked how he’s feeling, he answers that he is obviously not well; today marks nine days of his hunger strike.

“I feel weak, with a lot of heartburn,” says Pedro from the bottom bunk in the cell where he remains with 31 other inmates, some of whom help him get up, hand him a bottle of water, and open it for him, because his strength is running out, as much or more than his patience.

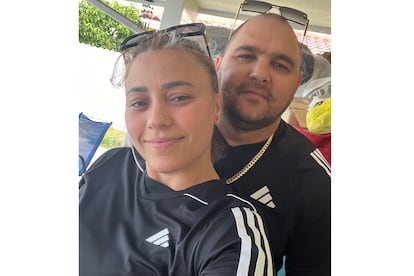

Four days ago he was taken to the hospital. His wife Daimarys Hernández, 40, found out because the partner of another detained migrant called to inform her. Scared, Daimarys immediately called almost every hospital in Miami, where she repeated the same questions: if they knew about him, a 44-year-old Cuban migrant detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and transferred to Alligator Alcatraz prison, who had refused to eat since July 22.

Every medical center responded that they had no news of a patient with those characteristics. They even denied his presence at Kendall Hospital, where she later learned Pedro had been handcuffed for three days while doctors tried to convince him to eat something. Pedro refused. He was offended when they suggested he drink a juice, now that “no one was watching.” He turned around and said, “Do you know why I can’t do that?” he now says, his voice cracking. “Because I have to respect myself and everyone who’s with me.”

This was the reason why he signed a document stating his intention not to receive any kind of assistance. “I don’t want food, I refuse any treatment. I didn’t even ask to be taken to the hospital, because I’m fighting for my family and all Cubans, and I belong where my people are, in prison, suffering the same hardship they are.”

A month before ICE arrested him, Pedro was nervous and agitated. He had seen more than once the images of officers detaining other Cubans in immigration courts or at traffic stops. Governor Ron DeSantis, a staunch ally of Donald Trump, has paved the way for collaboration with the federal government’s anti-immigrant offensive, which so far this year has accumulated more than 10,000 arrests in Florida alone and nearly 60,000 nationwide.

At 8 a.m. on July 8, Pedro and his wife showed up at the ICE office in Miramar, where he had routinely been showing up since a legal problem stripped him of his permanent residency and landed him in jail. More than 10 years ago, he was convicted of guarding a house with marijuana crops and later of serving as a chauffeur for people involved in credit card theft.

The United States tried to deport him twice, but Cuba never accepted him back. For some time now, he had been “calm.” He built a family. That morning, in Miramar, Daimarys waited for him outside the ICE office. Time passed, and her husband didn’t come out. Others walked out, but not him. Suddenly, Daimarys received a call from ICE on her phone. It was Pedro.

“My love, my love, I love you, I’m staying here, I love you, take care of yourself,” he told her. And Daymarys, who recounted the story and couldn’t stop crying, felt her heart clench in her throat. They’d known each other since 2006, ever since he, after two failed attempts, arrived by sea on a raft from Cuba. They have two children, whom they’ve raised and watched grow up. “In a minute, your life falls apart,” she says. “It’s been 19 years of being together.”

“I can’t live like this anymore.”

Pedro barely sleeps, perhaps two or three hours during the long, swampy Everglades nights. “Since I’ve been on hunger strike, I wake up a lot,” he says haltingly. Then he stops, gathers his strength, and continues: “When I lie on my back, it’s like I have a 50-pound (22 kg) weight on top of me; my stomach hurts. I deal with it and say I’m fine, but I’m not.”

In his cell, he has collapsed twice, and his fellow inmates have had to rush to help him up. The days are already taking their toll on his body, and no authority has come forward to find out much more, he says. Sometimes an officer stops and asks how he feels, only when his fellow inmates warn them that Pedro is getting worse. Yesterday, seeing his pale complexion and his pale, dry lips, they led him to the Alligator Alcatraz infirmary and checked his blood pressure. Then he returned to the cell he once imagined himself in.

The day after his arrest, when he confirmed his whereabouts to his wife, he said, “I’m where I told you they were going to bring me.” It was what he feared, and what many in Florida fear: ending up in the place that has become the fiercest and most symbolic face of Trump’s anti-immigrant crusade. A place erected in just eight days on a former airstrip west of Miami, built with tents, trailers, and wire fences, ignoring any environmental demands and right under the noses of the Miccosukee tribe, which has denounced the desecration of “sacred” lands.

In the words of Florida Attorney General James Uthmeier, Alligator Alcatraz is the place where “if someone escapes, there’s not much waiting for them except alligators and pythons.” The multi-million-dollar facility run by the State of Florida, which has the capacity to house approximately 5,000 beds—at a cost of $245 per day each—was designed to be a “rapid processing center.” That is, to facilitate the almost instant deportation of arriving migrants, of which, so far, there are no more than 1,000. At least 100 people have already been deported from the facility.

But Pedro says that if anything really tested his patience, it was realizing that the days go by and no one tells him what will happen to them. During this time, he could lose his job at AVS, an audiovisual services company, and he could be separated from his family. He no longer has control over almost anything, but he does have control over his body. That’s why he decided to go on a hunger strike.

“I’m no longer the master of my life on the streets. ICE can pick me up whenever they want, when they open a new prison. ICE is the one who decides my life,” he says. “And since my life no longer belongs to me, it’s up to them to decide whether I live or die. Because I’m not doing anything by going out onto the streets and continuing to live in this uncertainty, wondering if they’ll pick me up next year. They’re playing with people’s lives. They’re not considering the consequences of taking away a person’s freedom.”

Pedro has felt helpless seeing himself like this, in those cells, treated like a criminal. He remembers the day he arrived at the prison, where they bound his hands and feet and left him on the floor for more than 10 hours. He complains about the same things others have complained about: they don’t have a clock to tell time, they’re only allowed to shower three times a week, with no privacy, they sleep with the lights on 24/7, COVID-19 has spread like wildfire in the center, and there’s a lack of hygiene. A few days ago, the toilets in one cell overflowed, covering the space with feces. The officers took the inmates out, waited for the excrement to dry, and then put them back in.

“I can’t live like this anymore,” says Pedro.

A desperate family

During a call on Tuesday, Daimarys told Pedro she wanted to put one of her sons on the phone. When the boy heard his father, he asked, “Dad, aren’t they giving you food? Why aren’t you eating?” Pedro couldn’t answer, so he asked to talk to his mother right away. “He didn’t have the courage to talk to the boy anymore,” Daimarys says.

The mother struggled to explain to her children why their father isn’t home, why ICE had taken him away. She told them that Pedro had made a mistake in the past, and that now being punished for it once again. “It’s hard to tell your children that he’s doing things right and that he’s still paying,” she says. “If you made a mistake and paid for it, why does it still haunt you years later? And how long are you going to have to keep paying for something you already paid for?”

Pedro has told his wife he doesn’t want to talk to anyone else except her, whom he misses so much. Daimarys, in her job as a manicurist, sometimes has to bow her head so clients don’t see her tears. When she talks to Pedro, whom she can tell is tired, she always asks him to please eat.

“I’m scared. I try to convince him every day. I’d rather he be okay and alive, even if they deport him anywhere in the world, but okay,” she says. “But he tells me he’s already made his decision, that I shouldn’t ask him that anymore. He doesn’t want to be separated from me or his children, or be sent somewhere else. That would break up a family.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.