‘I’m going to ask for my deportation, I can’t stand being here one more day’: The life of a group of migrants in a Texas detention center cell

Over the course of a month, EL PAÍS followed the daily lives of several men held in a prison for foreigners that they call a ‘living hell.’ Speaking from the inside, they described the appalling conditions, the climate of fear, and the lives that have been taken from them by Trump’s anti-immigrant crusade

Juan Manuel Fernández-Ramos is convinced that, after 72 hours, everything that a prisoner says is a lie. An inmate told him he had five motorcycles in Mexico, and he replied that he had 10 in Cuba. Another prisoner told him he had thousands of dollars in savings for when he got out, and he retorted that he himself was hoarding millions. “We all know it’s a lie, but what are we going to talk about after five months here together?” Of his eight fellow inmates in cell A1, he is the one who has spent the longest time at the IAH Polk Adult Detention Facility in Livingston, Texas, where Donald Trump’s anti-immigration crackdown has sent many foreigners now awaiting possible deportation. There are days when Alejandro García, who sleeps on the next bed, turns to ask him what he thinks of immigration officers, if he thinks there’s a chance for them. “But I already told him not to ask me any more questions. Every time he does, I tell him a hundred lies. I’m not immigration, and I’m not ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement].”

Time passes slowly in prison, and sometimes it seems like it doesn’t pass at all, as if it’s always been the same long night ever since they arrived. In a series of video calls over four weeks, several inmates in the eight-person cell A1 told EL PAÍS what life is like inside, everything that they’ve lost and what they still yearn for. The men have no doubt that anyone who ends up in the Livingston center will be forced to leave the United States.

If that were the case, it would be painful for Juan. It would be like throwing away so many things: the 90-mile raft journey across the Florida Straits from Cuba; the house in Tampa; his three years of work as a Costco delivery driver; even his relationship with Jessy, his longtime girlfriend, whom he was about to marry when ICE officers stopped him. He was ticketed for speeding and driving after having a few beers in February, when he was just three minutes from home. However, if tomorrow they told him he was leaving for Cuba, he would also feel a great relief. Downtown Livingston is, this Cuban says, “a living hell.”

At 5 a.m., the guards open the cell’s creaking iron door to bring them breakfast: milk and cereal, sometimes some bread or oatmeal, or rice that tastes like plastic. “It’s inedible,” says Juan, 30, who takes a bite of something and then goes back to bed, the bottom one, on the second of four bunks that take up almost the entire cell. The rest of the space is taken up by a table and the bathroom, which has no doors, but where they’ve improvised a curtain so as not to see each other naked, urinating or defecating, or God knows what else.

“This is the ugliest thing I’ve ever seen in my life,” Juan asserts. “Here, the fat people get skinny, and the skinny ones you can’t see anymore.” He himself, who weighed 213 lb (97 kg), now weighs 185 lb (84 kg). He’s not sure he is getting the daily diet of between 2,400 and 2,600 calories that, according to Tricia McLaughlin, current Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs at the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), nutritionists have prescribed for each detainee in ICE centers. She said this after several accusations from migrants arrested across the country, upset by the inadequate food they are provided. The government official has refuted the allegations: “Ensuring the safety, security, and well-being of individuals in our custody is a top priority at ICE. Meals are certified by dietitians,” she said earlier this month.

After breakfast, there isn’t much else to do in cell A1. Some sit at the table and draw, others lie in bed staring at the ceiling, or turn on the television to watch a movie or soap opera. This in particular has caused them no small amount of trouble, because how do three Cubans, four Mexicans, and one citizen of Belize manage to get along with just one screen?

The same goes for cleanliness. Some don’t care, but Juan is tidy, fussy even, and he likes to keep the room clean. A few days ago, he poured toothpaste and soap into a bucket of water to mop the smelly cement floor and relieve the stench that condenses when the air conditioning is turned off, almost always between 5 and 8 p.m. in the humid summer in this area.

Those are the worst hours, the hottest times: eight bodies of various ages sweating in a space 20 feet wide by 25 feet long, a space that is becoming increasingly small compared to their overwhelming desire to get out of there. There are days when they take off their stuffy red and orange uniforms and strip down to their underwear. The officers don’t like this brazenness, but they have no choice; the heat is unbearable.

“It’s not normal heat. We’re locked up, there’s no air coming in anywhere,” says Juan. His cell probably should hold fewer detainees, not eight, but the national order is to apprehend 3,000 migrants a day, a figure that exceeds the official DHS capacity. In mid-June, ICE had nearly 60,000 people in its facilities, more than the number contemplated by Congress, whose budget provided for housing around 41,500. The government plans to resolve this situation with the approval of President Donald Trump’s mega-budget law, which, among other things, will allocate $45 billion to expand capacity in the country’s detention centers.

Meanwhile, complaints of overcrowding continue to pour in. Juan knows this all too well, as he can barely sleep, because when one of them wants to watch TV, another one is in the bathroom, or when one wants to turn off the light, another wants to grab the phone and talk to his wife, or throw a quilt over himself and masturbate.

At noon

It’s lunchtime. It won’t be a meal to satisfy their underlying hunger, but it’s something: almost always bread, with a hamburger or sausage, and a bit of cabbage. Other times, there are beans and tortillas. When their relatives can — some very occasionally — they send them supplies that the center sells, almost always cans of Maruchan soup, which would cost less than a dollar in any supermarket in the country, but which the center, operated by the private company Management & Training Corporation (MTC), sells for $1.15. Too much for them, and even more so for their partners, who now carry the burden of the entire household alone.

Alejandro, 34, fell ill with gastritis and has lost a lot of muscle mass since his arrest, about 17 to 22 lb (eight to 10 kg), which wouldn’t have affected anyone else, except that he has the body of a stripper, a physique he’s sculpted and cared for since his days in Cuba and which has allowed him to take to the stages of the La Bare club in Miami or Alma Latina in Houston, the places where he worked after arriving in the country across the border four years ago. Now he exercises when they take him out for an hour a day to get some sun in the courtyard, or he improvises planks while leaning on the table in the center of cell A1.

In March, Alejandro got into a street fight that ended with him being detained for two months in Harris County, Texas. The day his lawyer and the police told him he could return home, ICE caught him outside the police station and put him in a truck. “I didn’t even have time to see the street,” he says. He was then transferred to Livingston, where he has been for a month, in the same cell where he met Juan, who is now his friend and to whom, on the nights when he can’t sleep, he tells the story of his life or how much he misses his family. His 19-month old son, whom, if he is deported, he will never see grow up, and his mother, who is now going to self-deport to Cuba, because without him in the United States, nothing makes sense.

“Day-to-day life here is difficult and stressful. Sometimes we can’t talk to our family because calls are so expensive,” says Alejandro. His mother pays 25 cents a minute for rushing to ask him how he’s doing, what he ate, when he’ll get out of there, if he’ll ever get out.

A few days ago, Alejandro decided that enough was enough; he preferred to self-deport. Preferably to Mexico, because he has nothing in Cuba; just because he has a country of origin doesn’t mean he has somewhere to return to. His blood pressure is constantly shooting up; he’s depressed. He says that day-to-day life, surrounded by so many people from so many places, hasn’t been easy. “Living together is hard. Sometimes we argue; one day we’re fine, but the next we’re not. We try to share the little we have, but sometimes we fight over the smallest things, over a pair of underwear that goes missing, or over the television if it’s too loud.”

He’s given up. On July 3, he had his online appointment with the judge handling his case. “He won’t let you speak, he won’t even let you explain.” So he requested voluntary departure from the country, but was told he was only eligible for deportation. Then he returned to his room, unwilling to talk to anyone, and went to sleep. “The day I leave here, I’m going to remember the injustices ICE has done to us; there are so many things.”

The afternoon

By the afternoon of Thursday, July 10, no officer had approached cell A1, even though the inmates were scheduled to go to the barbershop. They were hairy and had repeatedly asked for a haircut, but the officers were unresponsive, nor were they responsive to their requests to change the sheets and bedspreads they had been using since their arrival at the detention center.

In cell A1, Emmanuel Hernández Timothy, a 41-year-old from Belize, reads the Bible. He does this to pass the time and to calm the anxiety caused by being confined in that room. A few days ago, he was close to fighting. “They put people of all nationalities together. There are people who have nothing to lose, who aren’t here fighting their cases, and they’re the ones who start fighting you. You have to defend yourself,” he says. If he fights, he’s sent to the punishment cell for 21 days, so he asked to change rooms and has now made friends with Juan, who sometimes shares the food his girlfriend buys him with the other inmates. There are others in the cell with whom he doesn’t get along.

In December of last year, someone reported to the police that Emmanuel was arguing with his wife in the car outside their Houston home. They drove him to the station. When he was released in May, as he was putting on his clothes to leave the prison, ICE officers arrived and detained him. He says he can’t stand another day in a cell. He has also requested deportation. “I told them: if you’re going to deport me, deport me, because I can’t stand being here anymore.”

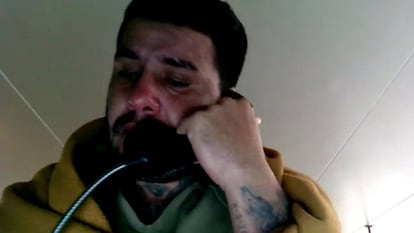

As he is talking, he bursts into tears, and apologizes. “I miss them so much. I wish I could be with my family. I miss spending time with them, eating with them. There are so many things I miss.”

Emmanuel left Belize in 1998. He went to Mexico, and four years ago, he crossed the border into the United States, looking for what everyone else is looking for. When he lived in Guadalajara, Mexico, where he had a plumbing business, he was stabbed in the neck and had one of his ears cut off. He had to leave, and now he’s afraid to return.

It’s the same fear his other cellmate, Jaime Navarro, a 54-year-old Mexican, feels. “I’m fleeing my country because they tore my tendons, broke my hand, and almost ripped off my heel.” He says it’s because of drug cartel issues.

His journey back and forth has been long. In 1987, he moved to California. Later, in Eagle Pass, on the Texas border with Mexico, he spent time guarding houses that hosted drug deals. “I didn’t know anything about what they had stored in there,” he says. He then returned to Mexico and, in October 2024, back to the United States once again. Now he fears being returned to his homeland. “I spend every day feeling very sad, afraid.”

Jaime is one of those who would prefer to stay in cell A1 forever. No one sends him any food, no one calls him, and no one will help him pay for a lawyer, but he has his reasons for preferring confinement to being sent to Mexico. Now, at 5 p.m., the officers will knock on the creaking iron door and give them a bit of bread for supper. They’re tired of so much bread. Of so much heat. Of so much confinement.

Rey Mendoza, a 41-year-old Mexican like Jaime, finds the idea of another day in prison unbearable. “It’s been very tough. The conditions here are terrible, there are cockroaches, crickets, the hygiene is very poor, they give us less and less, and everything is very expensive.”

Rey was arrested because one night last March he felt like eating some tacos. He was in his Dallas apartment, where he lives with his wife and nieces. He went downstairs, started his Chevrolet pickup truck, and crashed into the end of another car in the parking lot. It changed his life. He didn’t have time to get the tacos. Neighbors informed the police, and they caught him. The day he was due to return home after posting bail, ICE officers were waiting for him outside the police station. He’s been in Livingston since last April, four months that seem like an eternity.

It’s getting dark

The sun is setting in Livingston, Texas, but for the detainees, it doesn’t matter whether it’s 2 p.m. or 2 a.m. A prisoner’s time isn’t measured in hours, but in events. And Juan’s, the most definitive he’s had in years, will arrive in a few days. He has his last date with the judge, who will decide whether or not he leaves the country. Lying on the bed where he spends most of his time, he feels like he wants to be deported.

“I’ve been lying down for days,” he says. “Jessy tells me, ‘But you’re strong.’ I already told her I’ve run out of strength. I’m weak. I can’t get out of bed. It’s 23 hours locked up and one hour in a yard.”

On Saturdays, his mood changes a bit when he makes video calls with Jessy. The rest of the time, he doesn’t know how to deal with it. “I’m going to ask for my deportation. I can’t stand being here one more day. I’ve been here for almost six months,” he says. “Here in Livingston, no one can stand that long. Here they force you to sign the deportation papers.”

At 1 p.m. on July 7, 2025, Juan appeared before the judge, in an online hearing attended by his lawyer, to whom he pledged $15,000 to get him out of the detention center. This is an amount of money that he does not have, and which will leave him with a debt to pay back even when he starts another life, far away, no longer in the United States.

“It took two hours with the judges, but no one can beat them,” says Juan. The judge informed him that the asylum request wasn’t eligible, and that he could only grant him voluntary departure from the country. “I got angry and told the judge to do whatever he wanted with me. I don’t want to have anything to do with this country. The news depressed me, but when you go back to the cell, you feel like it’s better even to go back to Cuba.”

Juan’s lawyer then asked for five minutes to speak with his client. He calmed him down. He told him to consider the benefits of voluntary deportation, the route the government has sold to migrants to get them to leave, promising the possibility of future entry into the country through legal means and putting the CBP Home app in their hands, with which they would receive $1,000 for returning home on their own. As of April of this year, the last month for which data is available, about 5,000 people had self-deported.

Thousands more, with expired work permits and driver’s licenses, or languishing in immigration jails for a traffic violation, are also considering leaving the country on their own. It’s not deportation that the Trump administration is banking on in the long run, as it would be extremely costly to return more than 10 million migrants to their places of origin. It’s what they’ve dubbed self-deportation.

Juan had to pay $500 to leave the IAH Polk Adult Detention Center, and still they haven’t sent him home. He has until August 19 to buy a ticket and leave the United States. When he leaves, he will miss Alejandro most especially, but also the rest of his cellmates. Cell A1 will empty out as everyone is expelled from the country, one way or another. Their beds will be occupied by other men, with other names and faces, with the common knowledge of being immigrants.

Credits:

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition