Caravaggio, tariffs, and the dream of 1950s America

Reactionary thinking idealizes and falsifies a golden age of the United States, as portrayed by Bill Bryson in his memoirs

Reactionary thinking idealizes and falsifies a past that never really existed, but to which it seeks to return as a kind of Eden in the face of a present tarnished by horrible things, such as woke thinking, #MeToo, the investigation into slavery as one of the key moments in U.S. history, the 2030 agenda, the climate crisis, or equal rights regardless of skin color, sex, or religion. Behind the absurdity of the tariff war unleashed by Donald Trump, which could plunge the global economy and his own country into recession, lies not only a problem with the trade balance, but also nostalgia for an idealized America, stuck in the 1950s, before the hippies and the great changes of the 1960s.

In addition to being an extraordinary travel writer and a solid and entertaining popularizer, the American writer Bill Bryson is a great chronicler of American life through books like Made in America and The Lost Continent, which begins with a glorious phrase: “I was born in Des Moines. It had to happen to someone,” which sums up the feeling that the Midwest is the closest thing to being nowhere. He also has a beautiful memoir, The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, in which he describes his childhood in the dream America of the 1950s.

“I can’t conceive of a more pleasant place or time in history than America in the 1950s,” he writes in a book in which, despite recounting his happy childhood in Iowa, he starkly describes the institutional racism suffered by Black people and the anti-communist hysteria that drastically curtailed the liberties of many Americans. “No country had ever known such prosperity. It hadn’t been bombed, and it had hardly any competitors. All American companies had to do was stop building tanks and battleships and start making Buick automobiles and Frigidaire refrigerators... And they did. By 1951, when I decided to come into the world, nearly 90 percent of the country’s homes had refrigerators, and nearly three-quarters had washing machines, telephones, vacuum cleaners, and gas or electric stoves — things the rest of the world could only dream of.” Americans owned 80% of the world’s household appliances, controlled two-thirds of the world’s productive capacity, and produced more than 40% of the planet’s electricity, 60% of its oil, and 66% of its steel. The top 5% of the world’s population — the United States — had more wealth than the remaining 95%.

Trump dreams of the America Bill Bryson was born in, as if the past could return and as if society hadn’t changed since then. The symbol of what remains of that lost world is found in one of the country’s poorest and most violent cities, once a symbol of industrial power: Detroit, located in the same geographic area as the author of A Brief History of Nearly Everything’s native Iowa. The Detroit Institute of Arts is located in a no-man’s-land, between the more or less reclaimed downtown and the run-down areas, with abandoned houses and blocks and blocks that look like something out of a zombie movie.

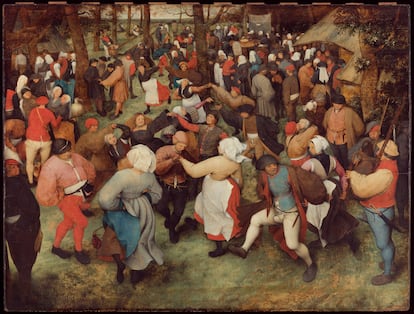

Its location makes this museum, which is among the finest in the United States and the world, particularly impressive. It is an Art Deco building that houses 65,000 works of art, reflecting the wealth and power of the American automobile industry, which had its epicenter in Detroit. There are not only paintings by Pissarro, Claude Monet, the murals of Diego Rivera: it was the first American museum to buy a Van Gogh, a self-portrait from 1887 that it acquired in 1922. Two masterpieces especially attract attention: a Caravaggio from 1598, Martha and Mary Magdalene, because there are very few works by this painter in the world, and one of the most famous canvases by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The Wedding Dance, from 1566, one of those works that have appeared on countless book covers and posters. The first was acquired in 1973, when the city was heading towards decline, and the second in 1930, when mass production of cars was beginning.

During the crisis that bankrupted Detroit and made life hell for its poorest residents — those with nowhere else to go — the city considered selling some of those paintings to restore services like public transportation, but it was impossible because no one had the right to do so. In reality, they belong to the past of a city that was and will never return. The problem with Trump’s tariffs lies not only in their lack of economic logic, but in the dream of the industrial America in which he grew up (he was born shortly before Bryson, in 1946), where everything was in its place and social and racial injustice were perfectly accepted.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.