Silicon Valley’s ultra-individualist philosophy wants to conquer the world

A handful of technocrats, convinced of their intellectual superiority, occupy key positions of power. They champion a supposed critical thinking — ‘think for yourself’ or ‘find your own truth’ — which they want us to pursue by surfing their social media platforms, where propaganda and disinformation thrive

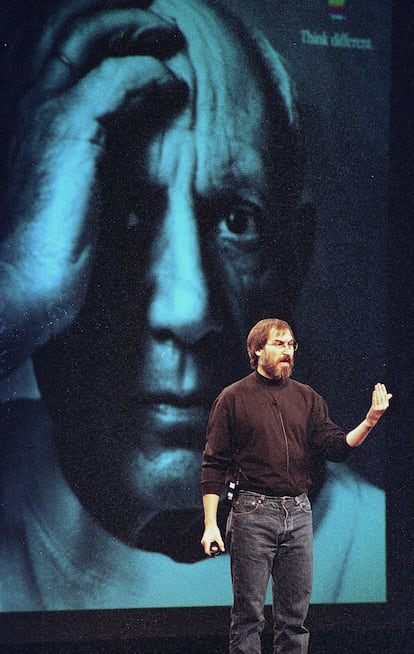

Let’s imagine two scenes that are pivotal in the history of technology and, by extension, in the history of humanity. In the first, we see a famous television commercial. As black-and-white images of icons like John Lennon, Pablo Picasso, and Maria Callas flash on the screen, actor Richard Dreyfuss recites a poem: “Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers […] Because they change things. They push the human race forward. And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.” The commercial concludes with the slogan “Think different.” It’s 1997, and Steve Jobs has just returned to Apple.

The next image is more recent, occurring just a few weeks ago. Apple, now the most valuable company on the stock market worldwide, and its CEO, Tim Cook — a staunch advocate for equality, regardless of gender, race, or sexual orientation — stands with a serious expression as Donald Trump’s second inauguration as president of the United States unfolds, an event for which Cook, like the rest of the tech elite, has made a financial contribution. Not far behind are Mark Zuckerberg (Meta), Jeff Bezos (Amazon), Sundar Pichai and Sergey Brin (Google), Elon Musk (X, SpaceX, Tesla), and Sam Altman (OpenAI). The next day, Trump will pose for a photo with Altman and Larry Ellison (Oracle), and will announce a massive investment in artificial intelligence, aimed at securing U.S. technological leadership in the field in the coming decades.

Together, they represented the end of the discourse advocating for the social freedoms once championed by companies that, though born of a capitalist West Coast, were free-spirited and radically innovative, always embracing difference. Steve Jobs couldn’t witness this moment, nor the rise of modern pseudosciences: he died at a young age from a mild form of pancreatic cancer that he chose to treat outside conventional medicine.

The great leaders of Silicon Valley no longer inspire us to “think differently”; instead, they urge us to recognize the superior vision of billionaire businessmen or authoritarian leaders. The Valley’s ideology is cloaked in the guise of critical thinking and exported globally as propaganda through its own social media platforms. It is behind slogans like “think for yourself,” “do your own research,” and “don’t let them think for you,” which have fueled disinformation, conspiratorial thinking, and polarization — defining characteristics of our time and the engine of populism. Once social consensus on knowledge is disregarded, the appeal of simplistic solutions rooted in extreme individualism flourishes.

What has happened? What has changed in Silicon Valley for its mythology of creativity and independence to now serve as a tool for populist obedience? Manuel Castells, sociologist, former Minister of Universities, and historian of the internet, offers answers from California. He outlines three stages. In the first phase, which produced world-changing figures like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, “the entrepreneur was the model and innovation the goal — more than money — individualistic but in solidarity with the world and in line with social values [such as feminism, environmentalism, and tolerance of religion and sexuality].”

Starting in the 1990s, large companies emerged, which turned into oligopolies. “Although they preached innovation and freedom, in reality, the accumulation of capital, and therefore the profit motive, were the dominant ideologies. They became capitalists and businessmen, rather than entrepreneurs and innovators, although they were liberal and tolerant in their speeches and in their lives.”

Since 2010, Castells says, we’ve entered a third phase, where 5G, satellites, and AI have driven the fast-paced rise of innovators known as the self-proclaimed “PayPal mafia” — in other words Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and Marc Andreessen, who sold PayPal to launch new ventures. “Alongside their undeniable capacity for innovation, they sought total power. They are demiurges aiming to create a new world and even expand it — Mars or the metaverse. Zuckerberg joined this group, so did Bezos,” says Castells.

The expert explains that their ideology is centered on the idea that “the best brains — meaning them — should seek power while pushing aside the ignorant plebs.” This, Castells believes, forms the foundation of their alliance with Trump. “They are libertarian technocrats who seek to occupy the state to impose their agenda. They are very dangerous because they’re convinced of their superiority and have material power. But above all, their goal is power. They are not Nazis, but they admire them.”

Castells continues: “They have no ideology — only egomania.” On the day of Trump’s inauguration, all eyes were on Musk, head of the Department of Government Efficiency, after he made a gesture on stage that resembled the Nazi salute. Philip Low, founder of neuroscience company Neurovigil and a former friend of Musk, doesn’t believe he is a National Socialist, but instead believes “it’s something much better — or much worse, depending on how you look at it. The Nazis believed that an entire race was superior. Elon believes he is superior to everyone. He thinks he is working on the most important problems.”

Among those absent from the stage, despite their deep connections to the new American order, were two other key members of the PayPal mafia: Thiel, owner of Palantir, the leading global cybersecurity company and a supplier to the Pentagon and CIA, and Andreessen, a powerful investor, creator of Netscape, and now an advisor to Trump, despite his Democratic past.

Thiel was described by his protégé, Vice President J.D. Vance — whom he financed politically — as “possibly the smartest person” he’d ever met. They met at Yale, where Vance studied and Thiel came to give a talk. Captivated by Thiel’s ideas, such as that the brightest minds are often bogged down in absurd competitions instead of moving the world forward, Vance worked in Thiel’s orbit as an investment fund manager in Silicon Valley.

In his book Zero to One, Thiel defends the exceptional nature of the great business leader who disregards social conventions. He writes: “It’s more powerful but at the same time more dangerous for a company to be led by a distinctive individual instead of an interchangeable manager.” This, in his view, explains why Asperger’s is advantageous in Silicon Valley. Thiel is one of the proponents of the new American reactionary right, advocating for the “dark enlightenment” championed by his protégé, Curtis Yarvin, an anti-democratic movement that proposes the government of a strong monarch, who would rule the country like a CEO. Thiel has even stated that democracy and freedom are incompatible.

Regarding Andreessen, it is worth reading The Techno-Optimist Manifesto that he published in October 2023 to understand his hodgepodge of inspirations: anarcho-capitalism, accelerationism, futurism, Nietzsche, Ayn Rand. Technology, he says, will make us free supermen. He dares to identify social responsibility, environmental sustainability, and ethics as enemies. It is also interesting to review a book he has recommended, The Courage to be Disliked, by the Japanese philosopher Ichiro Kishimi. It is a bestseller that has sold millions of copies spreading the ideas of the psychologist Alfred Adler (1870-1937). It states: “Adlerian psychology is a psychology of courage. Your unhappiness cannot be blamed on your past or your environment. And it isn’t that you lack competence. You just lack courage.”

Thus, as we enter 2025, we find a group of technocrats linked to political power, convinced of their intellectual superiority, courage, and merit (how could they not be, if the market has backed them by turning them into billionaires, if they spend their days planning space travel to Mars or building a superintelligence?). These technocrats control companies with unprecedented influence, and are fully aware of society’s dynamics and conflicts (remember, they invented or control social media platforms). They are attracted by the idea of a governmental power weilded by a totalitarian CEO in their image and likeness, and supported by eclectic convictions tailored to their needs.

But how does this new ideology of economic and political power resonate with its customers and voters? To explore this, it’s interesting to examine Mark Zuckerberg, who has followed a similar ideological journey to that of his own demographic. Using right-wing terminology, Zuckerberg has swapped “woke” for “free speech.” The “recent elections” feel like a “cultural tipping point toward once again prioritizing speech,” he said when announcing the end of his fact-checking program and changes to moderation policies that brought him closer to Trump.

Like Vice President Vance, he is a white American man who has just turned 40, whose influence is inseparable from the internet. Noel Ceballos, an expert on film and popular culture and the author of Conspiracy Thinking, recalls three 1999 films that embody the ethos of protagonists who break free from social conventions and choose their own destiny — ideas that align well with the mythology of the young right: The Matrix, Fight Club (“although many of its fans focus on the pill metaphor or Tyler Durden’s hypermasculinity while ignoring the film’s deeper message”), and Eyes Wide Shut, which continues to spark wild theories about its director’s intentions.

In the ideological pastiche that has shaped internet culture over the last decade and a half, we can see the rise of the heroic archetype, even the “chosen one” figure — whether in the Matrix pill memes, Ayn Rand references, or the popularity of poorly read stoics, as well as in authors like Jordan Peterson and Nicholas Taleb. A current TikTok slogan echoes the sentiment: “To be cringe is to be free” — the idea that allowing yourself to be embarrassed is the ultimate freedom.

Once free from social conventions, the unfettered mind is said to achieve true clarity. This premise, which can serve as the foundation of both Kantian critical thinking and the teenage musings of Steppenwolf, has gained significance in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic. And here lies the paradox: everyone accuses each other of thinking wrongly. Some focus on radical freedom of thought and expression, while others on fact-checking. As the obsession with refining reasoning grows (consider Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow), the left criticizes the right for embracing conspiratorial thinking and fake news, while the right accuses the left of herd mentality and abandoning innovation. This latter argument has extended beyond the U.S. to Europe.

Think for yourself, think like me

A headline from the Spanish satirical online newspaper El Mundo Today succinctly captures the confusion at the start of Trump’s second term: “Curiously, a young man who claims not to be manipulated defends the same ideas as the three wealthiest men in the world.” If there’s one phrase that signals someone is about to venture down a conspiratorial rabbit hole, it’s “think for yourself,” often followed by “do your own research” or “don’t let them think for you.”

Critical thinking remains, as Arendt argued, a moral imperative — but it runs into a trap here. “Science begins with curiosity about the unknown and what we wish to explain,” explains neuroscientist Carmen Estrada, author of The Inheritance of Eve, a book on the origins of science as a “collective task built among many who collaborate, supported by those who preceded us, and with the certainty that our discoveries will be continued by others.”

“If people really understood how the internet works,” Stanford University professor Sam Wineburg writes via email, “how keywords distort searches, how search engine optimization pulls the strings,” doing our own research “would lead to better decision-making.” But, he adds, “most of us are sailing blindly, with naïve overconfidence in our ability to make wise decisions about digital information.”

Wineburg, co-author of the popular fact-checking manual Verified, contrasts the concept of critical thinking with the need to “critically ignore”: “We live in an attention economy, where platforms compete to keep our eyes glued to the screen. Evaluating information requires critical thinking, but critical thinking fuels attention. On the internet, the first and most important act of critical thinking is determining whether information is worth critical analysis. Learning to ignore low-quality sources preserves our attention for the information that really matters.”

Let’s consider an online culture that promotes a misunderstood individualism, a complex world distorted by ignorance, the unrealized fantasy of democratized knowledge, and the psychological reinforcement effect of like-minded individuals, who were separated before but now gather in online communities. We’ll polarize with an information system perverted by algorithm owners whose companies thrive on the emotional chaos of social media. And we’ll find ourselves with populist leaders — economic and political figures admired for their independence (even from their own followers), who are self-proclaimed defenders of freedom, but who embrace those willing to “tie up loose ends” whenever it suits them. When you admire a leader who “thinks for themselves,” you are, in fact, admiring deeply emotional beings.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.