History’s lessons for the Ukraine-Russia conflict: How do wars get started?

Over the centuries all kinds of pretexts have been used to justify confrontation. While motives may be obscure, what is clear is that the consequences are impossible to control or foresee

In Rob Reiners’ 1987 classic film, The Princess Bride, the character of Vizzini, a ruthless Sicilian spy, states: “Starting a war is a prestigious line of work, with a long and glorious tradition.” When it comes to the story of Russia and Ukraine in 2022, far from being a fairytale conflict between the imaginary kingdoms of Florin and Guilder, the threat of an attack by the military and energy giant Russia against the sovereign state of Ukraine is very real.

History teaches us several lessons, one of which is that, over the centuries, all kinds of pretexts have been used to spark hostilities and, also, that the consequences of a conflict are always impossible to control or foresee. Moreover, once certain mechanisms have been set in motion, they are very hard to reverse. And though wars may have causes, they are not natural disasters as in the case of earthquakes: they are a tragedy triggered by a few and suffered by millions.

Canadian historian and Oxford professor Margaret MacMillan devotes a chapter in her latest book, War: How Conflict Shaped Us to the justifications used throughout history for wars and invasions, starting with Troy when “one man steals another’s wife” to the sinking of the battleship USS Maine in Havana Bay in 1898, an incident that was used to justify the US attack on Spain. The sinking of the USS Maine was largely embroidered by the media – one of the many storms of disinformation with which wars begin and at which Putin’s Russia is particularly adept. However, MacMillan argues that no aggression occurs in a vacuum. “The causes of wars can seem absurd or inconsequential, but behind them usually lie greater quarrels and tensions,” she writes. “Sometimes it takes only one spark to set ablaze an already smoldering pile of timber.”

In all conflicts, there is a turning point: a point of no return. In an article on the Ukraine crisis, the magazine The Economist recently quoted the British historian A.J.P. Taylor: “The First World War became inevitable once mobilization orders had been issued in Berlin.” The Economist added that “the complexities of early-20th-century railway timetables, upon which troop movements then depended, made any alteration virtually impossible.”

Few analysts think that, despite the disturbing Russian mobilization on Ukraine’s borders, a point of no return has been reached, but it is always easier to assess the past than the present. Netflix has just released the film Munich: The Edge of War, based on a book by Robert Harris, which tries to save the face of Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister who signed a pact handing Hitler the Sudetenland – the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia – in Munich in 1938, which paved the way for the Nazi dictator to prepare for outright war in Europe. The film depicts Chamberlain as a politician obsessed with World War I, who wants to avoid another slaughtered generation at all costs. “Until a conflict has begun, it can be avoided,” says Chamberlain’s character in the movie. Viewers, of course, now know what Chamberlain could not have known: that World War II was already unstoppable, because Hitler had made the decision to attack and was only looking to gain time.

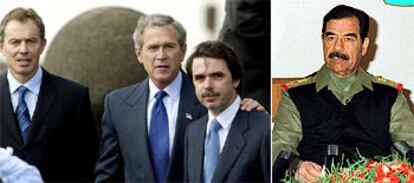

Meanwhile, the George W. Bush administration spent years inventing an intricate web of lies to justify the invasion of Iraq. A growing body of evidence shows that building the case against the Iraqi dictator, Saddam Hussein, began just days after the 9/11 attacks on Washington and New York. When did war become inevitable? Did any of the Security Council meetings prior to March 20, 2003, when the missiles began to rain down on Baghdad, do any good? Very likely not. And, of course, when millions of citizens around the world demonstrated against the war on February 15, 2003 – a civic rebellion portrayed by Ian McEwan in his novel Saturday – the White House had already given the order to invade, evident in the fact there was a huge military mobilization around the Persian Gulf.

Iraq is a typical case of a war in which everything seems to be under control – starting with the lies that are first sown – but which turns into a disaster with unforeseeable consequences. The past, again, offers numerous such examples. In 415 BC, Athens decided to launch an expedition against the powerful Greek city of Syracuse. The pretext was that two cities allied with Athens, which were rivals of Syracuse, had asked the authorities in Athens for help. In reality, it was a bid for Hellenic expansion in the Mediterranean and triggered another episode of the Peloponnesian war against Sparta. The Athenian forces were defeated in the port of Syracuse two years later, a military debacle that ultimately destroyed Athenian democracy.

The Athenian incursion also brought with it a terrible outcome, writes Donald Kagan in his book, The Peloponnesian War. This included devastating losses both in men and ships, widespread rebellions throughout the Empire, and the ushering in of the mighty Persian Empire. “These reasons contributed significantly to expanding the widespread observation that Athens was finished,” he writes. In 411, for the first time in a century, a dictatorship was installed in the city that had invented democracy.

Of all the disasters in history with unpredictable and devastating consequences, the most intriguing has to be World War I. Historians have been trying for more than a century to establish the real reason why the conflict began: five weeks elapsed between the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, and the outbreak of hostilities, during which time the European powers were unable to stop the senseless machinery of war that drove them towards the unintentional bloodbath. In his book The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, historian Christopher Clark uses that same term to describe the way in which those responsible for the outbreak of war walked resolutely into the conflict without any awareness that they were about to cause 20 million deaths and 21 million wounded as well as the destruction of three empires and, further down the road, World War II.

“How could Europe have done this to itself and the world?” asks Margaret MacMillan in her book The War that Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. “There are many possible explanations; indeed, so many that it is difficult to choose among them,” she writes. In the end, she makes it clear that “very few things in history are inevitable;” that the massacres of Louvain, Verdun and the Somme need not have happened. She also argues that “forces, ideas, prejudices, institutions, conflicts, all are surely important. Yet that still leaves the individuals, not in the end that many of them, who had to say yes, go ahead and unleash war, or no, stop.” Wars are declared – and prevented – by human beings. But, above all, it is human beings whose lives are destroyed by them.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.