A 3D view of the horror of World War I

A chance find in a Tangier street market has provided a never-before-seen look at life in the French trenches An upcoming book will reveal the collection to the world

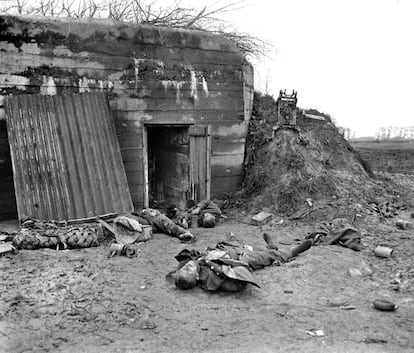

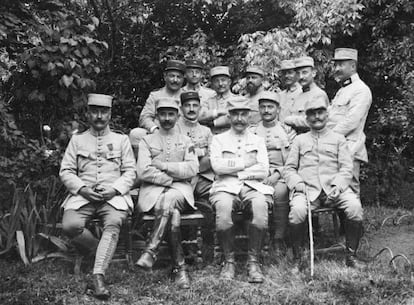

Some of the black-and-white photographs depict appalling scenes, while others are tremendously romantic and tender. Each one of them is a silent witness to a dark period in the history of humanity: World War I. Looking at them, it is impossible not to think about Paths of Glory, the 1957 movie in which director Stanley Kubrick captured the senselessness of the war and its miseries.

One might be tempted to think they were taken by the still-photography expert assigned to the filming of Kubrick's masterpiece. But in fact, they were shot by an anonymous service member who journeyed along the entire Western Front with his unit, north to south, taking pictures along the way.

The story of this collection began in 2003, when the photojournalist Pablo San Juan chanced upon some curious objects in a street market in Tangier: several small wooden boxes, each 15 by 20 centimeters, inside of which he found 50 glass plates with images on them. The salesman told him they were photographs, but that the images were reversed — no wonder, given that they were negatives taken with a Verascope stereoscopic camera.

When San Juan pulled out one of those negatives, he saw it depicted an old war of some sort. Intrigued, he called his friend Jesús Rocandio, a photographer from La Rioja who heads the Casa de la Imagen (CDI) photography conservation center in Logroño.

Among other activities, the CDI organized a 2011 international symposium on the restoration of old photographic material. Rocandio immediately told his friend to go ahead and buy all the boxes from the vendor.

When they arrived in Logroño, there was much rejoicing at the sight of what was clearly a photographic treasure: a collection of around 500 high-quality stereoscopic negatives, bearing dates, locations, and in many cases, even comments.

The photographer Carlos Trespaderne, a colleague of Rocandio's at CDI, notes: "Back then stereoscopic techniques involved a camera with two lenses and one shutter. The resulting image was doubled, and corresponded to each eye. Both were captured on a glass plate, the negative. When the information reached the brain, it created a sense of depth." It was 3D for the early 20th century.

The collection represents never-seen-before testimony of World War I, and "unlike most of the images that we are familiar with, these take us deep into the front, into the real war; we see the trenches, the weapons, the tanks, the cannon, the armies, the destruction... Never before had this war been viewed in such a way," says Trespaderne.

The collection comprises 500 negatives spanning from 1916 to 1938. The first block of 235 plates was obtained during the main battles of the war, including Verdun, Arras and the Somme. The rest depict the postwar era, and show family scenes and holidaymaking in Nice, southern Italy and northern Africa.

Although we know that the photographer was a soldier in the French Army, very likely an artillery captain — this is deduced from his careful comments about the caliber of the cannon — his identity has yet to emerge, since he did not sign his negatives. Researchers are now trying to find out who created this body of work of great documentary and esthetic value. The author of the images had a great eye for framing, his scenes are very well constructed, and he was very adept at composing an image for 3D viewing.

A decade ago, the CDI began the slow, painstaking process of preserving this material, stabilizing it, isolating it, reproducing it and undertaking a highly complex digital restoration process. "The boxes arrived in very poor condition. The climate in the north of Africa, so dry, was terrible for them — they even had termites," recalls Trespaderne.

In 2007 the CDI organized Bélica, an exhibition that displayed just a small portion of the material. Now it is working on a definitive show, as well as the publication of a book in 2014 to coincide with the 100th anniversary of World War I.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.