José Epita Mbomo, the Spanish electrician who sabotaged the Nazis

Born in modern-day Equatorial Guinea, Mbomo was taken as a teen to Spain where he became an airplane mechanic at a military air base. He caused a national stir when he married a white woman in 1936, went into exile in France after the Spanish Civil War, spent time in several internment camps and ended up leading a local group of the French Resistance. He was arrested and sent to a concentration camp in Germany, and survived an RAF bombing of the prisoner ship where he’d been transferred. EL PAÍS has reconstructed his extraordinary life based on newly found documents and family accounts

José Epita Mbomo

The Spanish electrician who sabotaged the Nazis

Ir al contenido

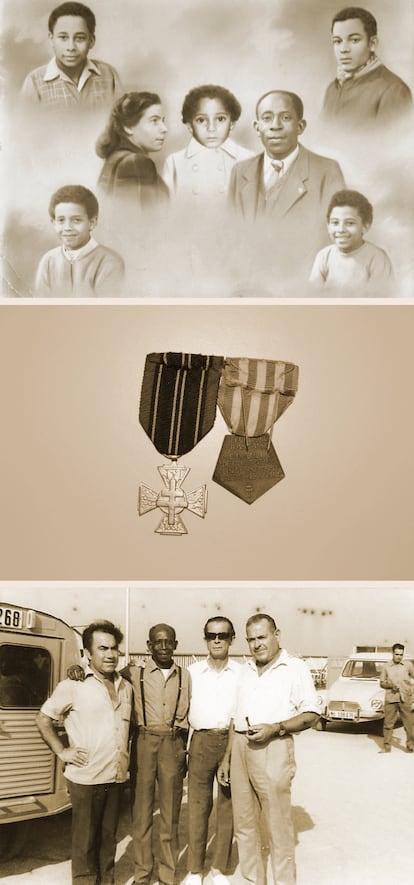

Guinean, Spanish and French, José Epita Mbomo was an airplane mechanic and the first Black man to marry a white woman in Cartagena, if not the whole of Spain. He went into exile in France after the Spanish Civil War and used his skills as an electrician to sabotage Wehrmacht networks and facilities. He was later deported to the Neuengamme concentration camp in Germany where he helped to save three lives, as far as his family knows. His war-time odyssey ended with his survival of the Cap Arcona massacre – the bombing by the British Royal Air Force (RAF) on May 3, 1945 of a German ship carrying 4,500 evacuees from Third Reich camps.

José was a modest man who scarcely ever talked about his war experiences with his five children, who would ask him about the scars on his back without ever getting an exact answer. He was an active communist back when communism was almost a religion, but tore up his party membership card when the Soviet Union crushed the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia. After leaving the Guinean island of Corisco in 1927, he had first-hand experience of the best and the worst of the 20th century. He was both victim and hero during Europe’s darkest hours. An ordinary working man, his epic experience was largely concealed from his family and is only coming to light now.

CORISCO ISLAND SPANISH GUINEA (1911-1927)

José Epita Mbomo was born on August 15, 1911 in Ibanamai, on the island of Corisco, which was then part of the Spanish colony of Guinea. He lived with his aunt Esperanza and attended a school run by the Claretian missionaries where punishments included kneeling on chickpeas, as he would tell his son, Andrés, years later.

On January 6, 1927, three seaplanes from the Atlántida Patrol landed on the island. Their occupants were on a military and scientific mission to establish themselves in the race for the skies and gather information that would help to map out the West African coast. The successful expedition returned to Spain with two Guinean teenagers – José Epita Mbomo and José Friman Mata.

(excerpt) "Little black Pepito Pita, 16, was brought as a passenger on the seaplane, Dornier, after being found on the island of Santa Isabel by Commander Llorente and his patrol companions, who, with the authorization of his aunt with whom he lived, managed to bring him to Spain. This little black boy will stay in Granada with his godmother, Lieutenant Salgado’s widow."

Both were employed at Los Alcázares air base in Murcia and had parallel careers until 1939. Friman then returned to the Murcia military base while Epita Mbomo went into exile in France, where he went on to fight another war. Years later, in 1956, Friman was interrogated about his former compatriot by the Franco regime but was unable to give details, stating that he had lost track of him in exile.

The 20th century began with flight fever. Airplanes were considered the weapon of the future and their development was accelerated by war; the first Spanish air raid took place in 1913, when German explosives weighing up to 10 kilograms each were dropped on the village of Ben Karrich in North Africa’s Rif region, then the site of fighting between colonial Spain and local Berber tribes. This was a decade after the first fuel-powered flight, and countries were vying with each other to see who could fly longer hours and distances. One of the most internationally renowned Spanish feats involved three Dornier Wal seaplanes that took off from the Spanish city of Melilla in North Africa and headed down to what is today known as Equatorial Guinea – a round-trip of more than 15,000 kilometers that was completed in 121 hours and 25 minutes. Its commander, Rafael Llorente Sola, received a Harmon Trophy from the International League of Aviators the same year that Charles Lindberg was awarded his for his solo flight from the US to France.

The trip from Melilla to Guinea involving three seaplanes was one of the greatest Spanish aviation feats of the 20th century. It covered 15,000 kilometers in 121 hours and 25 minutes.

The Air Force Historical Archive has preserved around 800 photos taken by the Atlántida Patrol as well as a report written by Llorente in 1944: “Most of the territories to be crossed had not been flown over by anyone, therefore it was not possible to rely on airfields or supply bases or repair shops, making it essential to place oil drums with the necessary gasoline and spare engines at specific points in the Canary Islands, Monrovia and Fernando Poo.”

LOS ALCÁZARES SPAIN (1927-1939)

Under the wing of Commander Llorente, the Guinean youths joined the workshop at Los Alcázares air base. Epita started there on April 4, 1927, according to records in the Official Journal of the Ministry of National Defense of October 28, 1938, in which his promotion to professional with lieutenant’s privileges is also noted. In that old fishing village, which was transformed by the arrival of the aviators, Epita and Friman became soccer strikers for the Alcázares Sports Club. There are references to both in newspapers such as La Verdad and El Liberal in 1932 and 1933, which were found by Javier Castillo, director of the General Archive of Murcia Region.

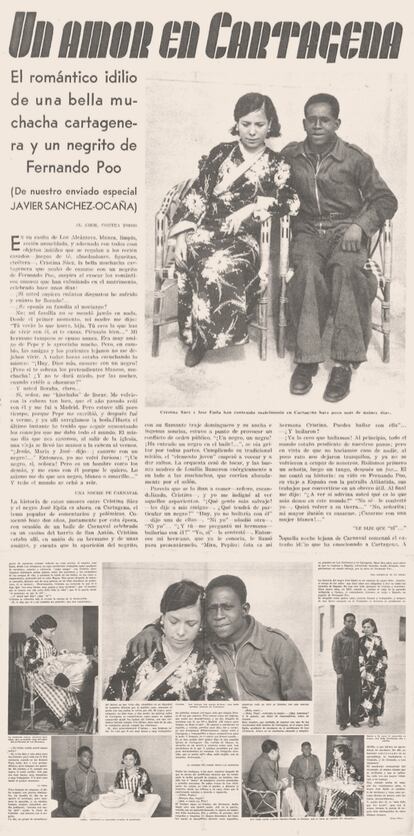

Before the war turned his world upside down, Epita married a white woman, Cristina Sáez, on New Year’s Day in 1936. Cristina was a brave lady from Cartagena who weathered hostility for her choice of husband and talked to the press about it when journalists were sent from as far as Madrid to interview the couple.

In one excerpt from the weekly magazine Estampa, the journalist Javier Sánchez-Ocaña asks the bride-to-be if her family had opposed the courtship, to which she replied: “No, my family never got involved. My mother told me from the start, ‘It’s your decision, my child. You’re the one who has to live with him. If you’re going to get married, think it over...’ My brother never objected, either. He was a close friend of Pepe [the Spanish nickname for José] and was very fond of him. But my friends and distant relatives wouldn’t leave me alone. They would say the same thing over and again: ‘Oh, my God! Marrying a Black man! But you have plenty of white suitors, girl! And won’t you be afraid at night when you are in the dark?’”

The photos from the magazine feature show José Epita in his air base work clothes and Cristina Sáez in a kimono, which adds a contemporary touch more typical of Los Angeles than Los Alcázares. Or perhaps that was the vibe in Spain before the bombings.

The couple had met in 1934 during a Carnival ball at the casino in the San Antón neighborhood. When Epita walked in, the other party-goers were aghast, according to Cristina. “People cried, ‘A Black man, a Black man! A Black man has entered the ball!’ The orchestra stopped playing and panicked mothers called their daughters, who ran wildly through the hall to their side,” she said two years later. “It was like they were going to eat him, and the fuss made me indignant. ‘What savage people,’ I said to my friends. ‘What’s so different about a Black man?’ To which one replied, ‘Oh, I wouldn’t dance with him,’ and another added, ‘Neither would I.’ Then my brother asked me, ‘And you? Would you dance with him?’ and I said, ‘I would, yes.’ So my brother, who already knew him, called him over to introduce us. ‘Look, Pepito, this is my sister Cristina. You can dance with her...’ he said.”

So they danced and became sweethearts and the young men in the neighborhood assaulted Epita for dating a white woman, and Cristina’s friends gave her a hard time for dating a Black man, and they broke up and she left for Madrid, and he went looking for her and they agreed to get married. It was a great love story. When they were wed in Cartagena, a crowd waited for them outside the Sagrado Corazón church. The wedding invitations had been issued by Commander Rafael Llorente and his wife María Teresa Flores for their “godson,” José Epita.

By then, Franco’s coup was not far off. “Los Alcázares air base remained loyal to the Republic, which had established a pilot training school there,” explains Javier Castillo, co-author of Los Alcázares en blanco y negro (or, Los Alcázares in in black and white) together with Juan Francisco Benedicto Martínez. “It was a base with a very progressive atmosphere, unlike that of San Javier, which belonged to the Navy and where almost all the officers joined the uprising. On July 19, 1936, the commanders and troops of Los Alcázares took over the San Javier base,” adds Castillo, who is preparing an exhibition in the General Archive of the Murcia Region of the 400 Murcian deportees who ended up in Nazi concentration camps.

In January 1939, Cristina Sáez, her two children and her mother María Contreras travelled from Los Alcázares to Catalonia in her brother’s taxicab. The Republicans had lost the war and the family was heading for France. They were helped by a woman named Elvira Sagrera who let them stay with her for a few days in Banyoles, in Girona province. Unfortunately, the family were split up at this point, and Sagrera would later write in a letter dated May: “Pepe came on January 29 and was very upset because they had left [...] The Nationalists must have been very close. During his stay he made every effort to find out where they were, and was told they were in a hospital or a shelter in France.”

MÉRIGNAC FRANCE (1939-1944)

Epita crossed into France on February 6, 1939. His daughter Esperanza discovered the date in one of her father’s work notebooks. Recently, she decided to look at it again and found something she had missed: her father’s comings and goings from French internment camps that were used to hold Spanish refugees fleeing the Civil War and its aftermath – Saint-Cyprien, Argelès-sur-Mer, Gurs, Septfonds – over a period of 10 months in 1939.

On December 6, he started working for a company in Bordeaux. Another war was starting and his expertise was probably appreciated. At some point, the family was reunited. “We don’t know when he joined my mother again,” says Esperanza Mbomo. It can’t have been easy despite the fact they both spent time in the same internment camps and slept on the same sands of Argelès-sur-Mer.

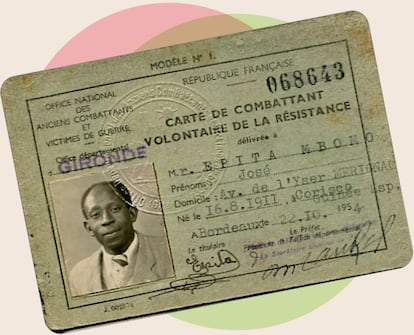

The family settled in Mérignac, in the Gironde department of southwest France. Epita worked as an electrician for a company contracted by the local air base. In 1942, he joined a mixed Resistance group known as the French Snipers and Partisans of the South/Spanish Guerrillas. That year they blew up a garage belonging to a battalion of German motorized troops in Bordeaux and destroyed the underwater cable linking Mérignac airport to Wehrmacht units on the Atlantic coast. “I can’t say for sure, but it is likely that he participated in all that,” says his grandson, Yvan Mbomo, who has formed a picture of his grandfather as a communist of such firm convictions that he put the fight for his ideals before his family’s safety and his own. On April 1, 1942, he became the head of the local Resistance group, under the orders of Julian Comme, who years later certified that Epita participated in acts of sabotage and propaganda with “discipline and love to liberate France.”

On March 28, 1944, after Epita’s third child was born, he was arrested by the French police.

NEUENGAMME GERMANY (1944-1945)

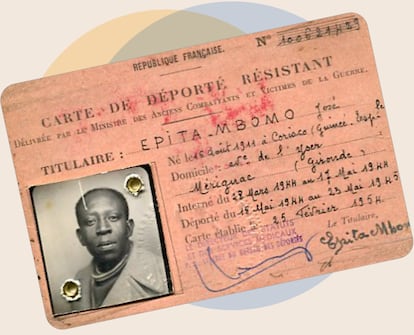

Epita was deported along with 200 other Spaniards to the Neuengamme concentration camp, south of Hamburg, entering the camp on May 24, 1944. “He was deported for political, not racial reasons,” says Alicia Pérez Comesaña, a researcher at Rovira i Virgili University (URV) in Tarragona who had access to a large database of Nazi victims, thanks to an agreement with the Arolsen Archives in Germany. “Until now, we knew of seven Black prisoners in Neuengamme, all members of the Resistance against the Germans. Now we know that there were at least eight.”

Despite the fact that the SS destroyed almost all documentation on the 100,000 Neuengamme prisoners, new information is coming to light. “More than 500 Spaniards passed through Neuengamme,” adds Pérez. “Besides José Epita, we at the URV have identified other Spanish deportees we didn’t know about.”

Both Alicia Pérez Comesaña and the historian Antonio Muñoz Sánchez, who has conducted research into Spanish forced labor during the Third Reich, believe that Epita’s trade may have contributed to his survival. “While many of his Spanish comrades were assigned to teams scattered throughout northern Germany to perform very hard, exhausting tasks, Epita stayed in Neuengamme and probably worked in one of the armament companies there, where specialized workers were highly appreciated and treated less harshly,” says Muñoz. “The fact that he was Black might even have worked in his favor. Within their crazy racism, the Nazis saw the handful of deportees of African origin as exotic beings, and put them to work as waiters, for example.”

And that was the case with Epita: he worked as a mechanic or electrician by day and as a waiter by night. “It allowed him to take leftover food, things like stale bread and potatoes, back to his companions,” says Esperanza Mbomo.

Esperanza’s brother Andrés has gathered similar accounts. “I have met three of his friends from the camp who all separately told me the same thing: ‘You have an extraordinary father, if he hadn’t given us food every day, we would be dead now.’” Sometimes the “survival” menu included rats, recalls Rafael Mbomo, another one of Epita’s children.

One of the few stories of Neuengamme that Epita told his family was that there was a hunt to find those responsible for making defective parts, but as he signed all the mechanical parts he produced, he was saved from a grisly fate.

José Epita may have been on a death march or traveling in an overcrowded freight car from Neuengamme to Lübeck, a distance of about 70 kilometers, when the Nazis evacuated the camp at the end of April 1945. He was imprisoned on the Cap Arcona, a German luxury liner converted into a floating jail that had been used in the filming of a National Socialist version of a movie about the Titanic in 1942.

“There were no provisions, no toilets, no water for the prisoners, who were crowded in the holds,” writes Richard J. Evans in The Third Reich at War. “When the SS opened the hatches, large pots of soup came down, but there were no bowls or spoons, and much of the food fell to the floor of the hold, mixing with the rapidly increasing excrement.”

On May 3, 1945, the RAF 263 Squadron bombed the ship along with others anchored in the Baltic Sea, causing one of the greatest maritime tragedies in history. The ship caught fire. The SS had removed the life-saving equipment and cut the fire hoses. “The castaways fought to the death (literally) for something to cling to in the water, only to end up perishing anyway from wounds, hypothermia or simply exhaustion,” wrote Air Force Captain Rafael Morales in an article on the incident in the Navy’s General Review. “It has been said that the RAF concealed the truth from its pilots about the real nature of the sunk targets and the identity of their victims for decades, and it must be true, because in the official British history accounts there is no mention of these extreme actions.” Nor do books such as Antony Beevor’s The Second World War or more specialized essays such as Michael Burleigh’s Moral Combat reflect the RAF’s fatal error, which German and French historians have scrutinized to a greater extent.

Of the 4,500 prisoners aboard the Cap Arcona, a mere 350 survived, one being José Epita Mbomo.

MÉRIGNAC FRANCE (1945-1969)

Epita told his family that he survived because he knew how to swim. But he recounted little else; nothing about the ship or the concentration camp or the Resistance or the Spanish Civil War because he was a man of restraint. Like other survivors of historical catastrophes, he buried the trauma in silence. “My father was a quiet man who said nothing about the things we see documented now,” says Andrés Mbomo.

Epita did what he had to do, including sabotaging the Germans and saving the lives of his friends in the concentration camp, without boasting about the good or dwelling on the bad.

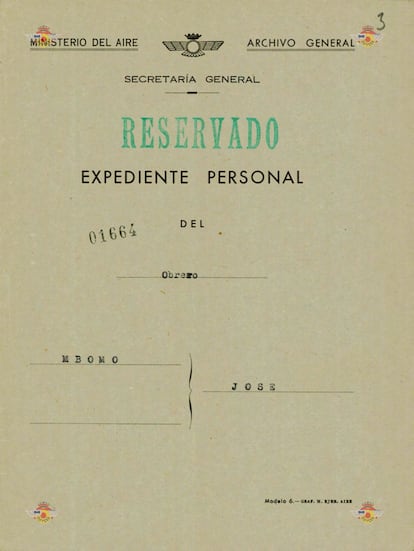

After the war, he returned to Mérignac with Cristina Sáez and their children, and worked until his death at the electricity company Forclum. In 1956, Franco’s General Directorate of Security asked for reports on his background: “As the General Directorate of Morocco and the Colonies is interested, I ask that you issue orders to provide all the existing information and data concerning JOSÉ MBOMO, son of José and Catalina Buambuha, Benga tribe,” reads the file kept in the Historical Archive of the Air Force and consulted by EL PAÍS. According to his grandson Yvan Mbomo, the date coincides with the moment that the family was processing a nationality and surname change from Epita to Mbomo with the French authorities. “At that time, my grandparents wanted to prevent their eldest children, who were born in Spain, from having to do military service or be declared deserters,” he says.

In 1968, Epita tore up his communist membership card while watching Soviet tanks crush the Prague Spring on TV. The following year he returned to Spain for the first time, spending the month of August in Cartagena with his wife and being reunited with old friends again in an emotional encounter.

On his return to France, he was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease and died on December 19, 1969, in a hospital in Bordeaux. The French Republic awarded him posthumous honors in 1975 for his participation in the French Resistance. When his daughter Esperanza had asked him about the scars on his back, Epita did not give her a straight answer. What he did say was: “We must never forget, but forgive, yes. I have forgiven.”

Images, documents and testimonies provided by the family of José Epita Mbomo and Cristina Sáez, the researchers Alicia Pérez Comesaña, Antonio Muñoz and Javier Castillo, the Historical Archive of the Air Force and the Murcia Region’s General Archive.

- Credits

- Coordination: Alberto Quero and Guiomar del Ser

- Art direction: Fernando Hernández

- Design: Ana Fernández

- Layout: Nelly Natalí

- English version: Heather Galloway