The advent of bacteria that can detect if a tumor is developing and destroy it

New studies indicate that genetically-modified microbes are likely to play an important role in the war against cancer

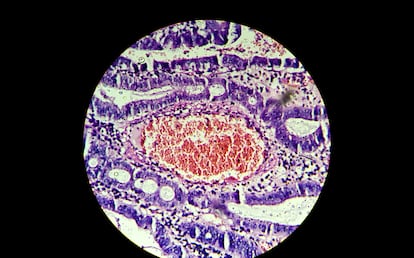

Cancer treatments began with aggressive cocktails of chemicals and evolved with the creation of drugs from cells. Now, living beings are being incorporated into the war against cancer. A few days ago, a team of researchers from the universities of San Diego (United States) and Adelaide (Australia) presented a study in the journal Science in which genetically modified bacteria were used to detect tumor DNA in the intestines of mice. This function could be incorporated into other projects, which have managed to send bacteria — modified to carry therapeutic payloads — into solid tumors. In this way, researchers were able to breach the barriers that tumors use to protect themselves from the immune system and directly apply medications, which has been a longstanding challenge.

In the recent work published in Science, researchers modified the ability of bacteria to adapt to their environment, a feature known as horizontal gene transfer. Unlike vertical transmission, which occurs between parents and offspring, microorganisms are able to exchange genes, and the capabilities they provide, among themselves. This property facilitates the spread of antibiotic resistance. Although it was known that bacteria had this ability, the researchers saw that this same exchange was possible between mammalian tumors and human cells and bacteria.

Of the bacteria that populate the intestine, Robert Cooper, from the University of California in San Diego, chose Acinetobacter baylyi for the study. The bacteria were modified so that they could identify the mutated KRAS gene that is behind many tumors. The bacteria incorporated that DNA, which was later used to detect if the mouse from which it had been extracted had developed a tumor. Researchers now want to use these bacterial biosensors to detect other types of tumor and microbial infections.

Advances in synthetic biology are not only making it possible to recruit bacteria to warn of potential tumors, they are also enabling bacteria to annihilate tumors. A team from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), for example, has used bacteria directed with ultrasound to deliver drugs to tumors. It has achieved this by taking advantage of tumors’ defense mechanisms to evade the immune system. Cancer cells are able to create an immunosuppressive environment that keeps cells such as T lymphocytes at bay. But this also makes it easier for bacteria to settle there. In the Caltech study, researchers modified the bacteria to transport drugs that would not otherwise reach the tumors. What’s more, they developed an ultrasound system that activated the release of the drug, meaning they could target harmful cells and avoid damaging healthy ones.

The authors of the study in Science warn that their work is a proof of concept, but they already have ideas about how it could be applied to patients. “Administration could be as easy as taking a probiotic pill [with the modified bacteria inside],” explains Robert Cooper, the lead author of the paper and a researcher at the University of California, San Diego. The bacteria would then be extracted for analysis through stool, urine or blood samples.

According to Cooper, the limitations of detecting tumor DNA this way are that the bacteria are only able to capture the known mutations that they are designed to detect. “However, colorectal cancer tends to have a few very common mutations that trigger it,” he notes. Furthermore, the intestine is full of bacteria, i.e. the famous intestinal microbiome. This would make it very easy to incorporate the biosensors, as the environment is well-suited to bacteria. This feature would make this method superior in sensitivity to liquid biopsies, which require more time for a solid tumor to develop and begin to spread tumor DNA in the blood.

In the future, scientists hope to expand the system so that it is possible to identify more than one mutation. The plan is to incorporate new modifications to the bacteria and to make cocktails with different bacteria that detect different mutations. “DNA detection will probably have to be combined with other screening methods, because not all tumors will have a different mutation, but it may at least be possible to reduce the frequency of colonoscopies,” concludes Cooper.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.