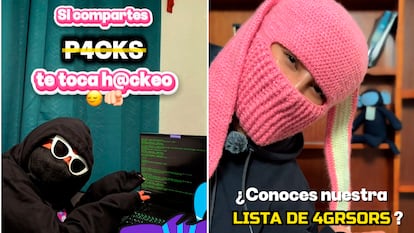

The Mexican hackers hunting pedophiles on the internet: ‘It’s becoming much easier to perpetrate this type of violence’

The DLR collective constantly monitors online activity, where it denounces practices such as the dissemination of intimate content without consent or child exploitation

The notification pops up. One of the 350 members of the Telegram group has just sent a photo of a young student from Oaxaca, who had just returned home from school, wearing a skirt. A cascade of messages begins in the chat: “It’s impossible not to look at how her skirt adjusts,” “lift it up more,” “what’s she wearing, a thong?” “she’s so hot.” The disturbing conversation takes a sinister turn when one of the participants reveals who sent the image: “I think he said up there that it was his daughter or stepdaughter.” These are some of the messages revealed at the end of November by the DLR Collective, a small team of hackers fighting against digital violence. The Telegram group included adults, but also minors. The publication of the conversation on social media led to an investigation by the Oaxaca Attorney General’s Office, which began interviewing students from the two high schools in the capital where the victims study. Despite the seriousness of the issue, it is just one of the hundreds of complaints that the DLR Collective says it receives daily.

Andy Torres was receiving about 50 complaints a day on social media when he launched the team in 2020. Almost six years later, the number has multiplied, reaching 800 to 1,000 a day. “The increase is overwhelming; this type of violence has grown significantly. Although, more than it growing, I think we’ve started to identify digital violence more easily,” says Torres, CEO of the DLR Collective. The current DLR team consists of nine employees, but only four handle all the complaints. “Much of what we do is automated. Sometimes you take down a server that hosted 10 sites, and that takes down 10 cases. That simplifies this part of the work. But [the fact that there are so few of us] takes people by surprise,” he says.

The team accessed the Telegram chat through a link shared in a WhatsApp group with over 1,000 users, nearing the app’s limit. Torres asserts that the same types of photos of minors were being shared there as well. Upon accessing the group, they noticed a change: “It was a group that shared intimate content of women. They were all adults, but suddenly someone encouraged sharing photos of minors, and that’s how this all started.” In that Telegram conversation, one user was sharing photos of his stepdaughter, another of his cousin. The images then began to surface.

Torres considers the increase in these cases very worying, but equally so the ease with which they are carried out. “It’s becoming much easier to pick up a device and start perpetrating this type of violence,” he emphasizes. This is a visible example of a reality present on social media, a phenomenon that has also managed to cross the barriers of other platforms like Facebook. There, Torres’s team has also detected groups where images of girls with sexual connotations were uploaded, without necessarily showing nudity. “It was like an invitation for other people to join their group and, from there, move them to another platform, like Signal or Telegram,” he says. The group contacted Facebook to delete one of these groups because they noticed that the number of followers was increasing exponentially, even though people were sharing it to report it: “When we first saw it, there were only 1,000 users. In about two hours, there were 4,000 and growing.”

It’s a similar case to “Daddy’s Princess,” a Facebook group that has become the center of a public debate. Users were sharing sexualized images of women and girls in a forum with over 20,600 members. On that occasion, the “We r women on fire” community exposed the messages being shared: “With patience and saliva,” “anyone share videos of girls?” The Nuevo León Attorney General’s Office and state police have already launched investigations into the case.

Artificial intelligence has also carved out a space for itself in digital sexual violence, extending beyond the screen. In 2023, authorities in Mexico City arrested a former student at the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), accused of taking photos from his female classmates’ social media accounts and altering them with AI. The investigation by the Mexico City Public Prosecutor’s Office revealed 166,000 edited photos and some 20,000 videos. “We’re talking about a huge number of images that ended up being used for harassment, extortion, and many other things. What we sometimes fail to realize is that something as small as modifying an image can cause violence to shift from a platform to a physical environment,” Torres reflects.

Although they lack concrete data, the information gathered over the years by the DLR Collective shows that women and girls are the most-affected by this type of digital violence and the leaking of intimate content: “We have two age ranges: the older one, for women, is between 25 and 35 years old; and for children, we’re talking about ages eight to 12.” However, they clarify that the phenomenon is intergenerational: “We’ve had cases of very young women, but also of women as old as 80, whom you wouldn’t imagine could experience this type of violence.”

The leaked Telegram chat mobilized authorities in Oaxaca. This is one of the reasons Torres believes it’s worthwhile to report these acts. “Authorities are starting to pay attention. In Mexico, we already have legal reforms that allow us to punish or penalize these types of actions, but unfortunately, there haven’t been enough cases to bring them to court,” he explains. “The more reports there are, the more attention judges will start paying to these kinds of cases.”

Public exposure, Torres says, is also a tool that puts the aggressor in a more vulnerable position. “When I started doing this work, people used their profile picture, their real name, their personal phone numbers. They weren’t ashamed to share someone’s photo […] Nowadays, they try to be careful, they hide, and so on. We’ve noticed that it really hurts the aggressors.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.