The Cartel of the Suns, the criminal network pitting the US against Venezuela

Washington’s latest offensive against the Maduro government is sowing uncertainty in the region, with the war on drugs as a backdrop

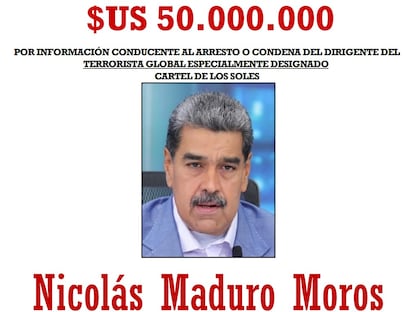

Brown eyes, black hair, standing at 6′2. Nicolás Maduro’s face appears in the foreground beneath eight large red numbers. This is the sum of money U.S. authorities are willing to pay for information leading to his arrest: $50 million (almost €43 million). However, the reward poster, published in early August, does not mention a single line about Maduro’s political career. He is not described as a dictator or as the architect of fraud in last year’s Venezuelan presidential elections, two recurring claims in Washington’s repertoire. Instead, Maduro is wanted for allegedy being—according to the White House — the leader of the Cartel de los Soles (Cartel of the Suns), a narco-terrorism network that presumably reaches all the way to the very top of the Chavista regime and connects it with the most powerful criminal forces in Mexico and Colombia.

“If you’re looking for a mobster, look elsewhere,” the Venezuelan leader responded in an explosive press conference last Monday. At the same time, he said he was ready to declare his country in “armed struggle” if it suffered any aggression. A day later, the Donald Trump administration announced a “lethal attack” against an alleged drug boat from Venezuela in Caribbean waters. Eleven people died in the operation. The Maduro government asserted the video was “very likely created using artificial intelligence.” All in all, this is the most serious incident in the recent escalation of tension between both countries.

The pursuit of the so-called Cartel of the Suns has been at the heart of the latest clash between the two countries, but it’s not a new phenomenon. The name dates back to 1993, when the links of two Venezuelan National Guard generals to drug trafficking came to light. The suns are a reference to the insignia worn by military personnel on their uniforms.

Three decades later, that term has expanded to encompass Chavismo’s alleged ties to organized crime. Washington has recently been using it almost interchangeably with the Tren de Aragua, despite being a distinct organization. “The Cartel of the Suns is a Venezuelan drug trafficking organization comprised of the highest-ranking military and officials,” reads one of the legal cases opened by the White House.

It was initially led by Chávez, claim U.S. authorities, adding that after his death in 2013, Maduro assumed the presidency and headed the organization’s massive cocaine trafficking operations. Just below him, the U.S. alleges, are other notable Venezuelan officials: Diosdado Cabello, the regime’s second-in-command; Vladimir Padrino, Minister of Defense; former Vice President Tareck El Aissami; and Maikel Moreno, Supreme Court Justice.

“It’s an atypical cartel: a criminal structure within the Venezuelan state, an informal corruption network that doesn’t answer to a single leader,” says Mercedes de Freitas, executive director of the NGO Transparency International for Venezuela. This diffuse nature, contrary to the rigid hierarchy attributed to the more well-known cartels, has been the subject of debate among experts and politicians.

Phil Gunson, Crisis Group’s senior analyst in Venezuela, doubts that it is truly a cartel as such: “There has never been clear evidence that such an organization exists.” He is not the only skeptic: “The Cartel of the Suns does not exist; it is the far-right’s fictitious excuse to overthrow governments that do not obey them,” declared Colombian President Gustavo Petro last week. “What there is, however, is abundant evidence of the links between several Armed Forces commanders and drug trafficking; they are two different things,” Gunson clarifies.

Much of the criminal universe that exists in Venezuela is a result of the country’s peculiarities, such as the U.S.-imposed blockade, crises due to economic mismanagement, and a surge in corrupt pacts to buy loyalties, experts point out. There are human trafficking syndicates that capitalize on the mass exodus of Venezuelans or the smuggling of gasoline, oil, precious metals, and other minerals. These alliances with drug gangs and militias are widely documented, especially in the border area with Colombia.

“The operation of criminal groups in Venezuela is not alien to the state,” Freitas asserts. The distribution of these clandestine profits, he maintains, is key to the regime’s political survival. “Maduro is part of the nodes that run these networks, he earns a lot of money, and compensates for his lack of legitimacy by maintaining this structure,” he adds.

Gunson emphasizes that the role of the government, often seen as a regulator of criminal dynamics, has evolved: “Since Chávez came to power [in 1999], corruption has been used as a control mechanism: you know that this general or minister is involved in drug trafficking or the looting of public resources, and you have control over him.”

The U.S. went a step further. In 2020, at the end of Trump’s first term, the White House filed a case against Maduro and 14 other Chavista leaders for narcoterrorism, corruption, and drug trafficking. It had gathered evidence for 20 years. Washington accuses the Venezuelan leadership of trafficking arms for the Colombia guerrila group FARC and its dissidents, orchestrating massive drug shipments with Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel, collecting million-dollar bribes from criminals, selling previously seized stashes to its allies, and ordering the kidnappings and murders of rival bosses and informants.

“During their meeting at the headquarters of the Military Intelligence Directorate (DIM), after the witness had been tortured and beaten for more than 20 days, the accused approached him and said: ‘You’re going to die here, you’re screwed, now go tell the gringos to get you out of here,’” reads the file against Hugo "El Pollo" Carvajal , former head of the DIM, last apprehended in Madrid in 2021 and extradited to the U.S. in 2023. The documents describe the use of the presidential hangar at Maiquetía Airport (the most important in the country, in Caracas) to prepare cocaine shipments, deliver documentation and official uniforms to the bosses, or negotiate prices for weapons and drugs under the command of General Carvajal, for whom the U.S. offered $10 million.

The trial of El Pollo, the highest-profile member of the Cartel of the Suns in U.S. custody, was scheduled to take place this year. But three weeks after prosecutors revealed that around a dozen witnesses and collaborators — former officials, former military personnel, guerrillas, and drug traffickers — were willing to take the stand in exchange for reduced sentences, Carvajal pleaded guilty to avoid the dock. In 2024, Clíver Alcalá, another general accused of belonging to the cartel, received a sentence of nearly 22 years in prison after signing a plea agreement and admitting to supplying bazookas and grenades to FARC dissident groups.

The list of high-ranking officials and members of the Chavista secret circle who have paraded through the halls of the U.S. justice system over the last decade, either as detainees or as witnesses, is endless. And it has influenced the construction of the cases opened against the Maduro government. In 2014, for example, Leamsy Salazar, Chávez’s former security chief, fled to the U.S. under the protection of the DEA and declared that Cabello was one of the leaders of the Soles, long before Trump even entered politics.

It’s a legal strategy similar to the one used in the U.S. against Mexican cartels: seeking the collaboration of lower-ranking bosses to catch bigger fish. “It doesn’t mean that what these witnesses are saying is false, but often they are people seeking the approval of the authorities to reduce their own sentences,” Gunson points out. It’s also a way to tighten the siege on the Venezuelan regime and encourage whistleblowing.

Trump’s return marked a renewed push for tougher measures against Maduro. Gunson, however, believes the naval deployment in the Caribbean and the campaign against the Cartel of the Suns have served to strengthen the Venezuelan leader internally and claim that he faces “an unprecedented threat” in order to counter his lack of popularity.

A quarter of the world’s cocaine

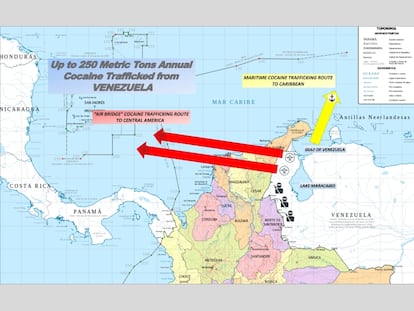

But former Democratic president Joe Biden’s negotiating approach failed to resolve the crisis: Chavismo has perpetuated its hold on power and maintains control of the country. It also controls the underground economies. Transparency International estimates that, under the protection of that country’s government, drug trafficking generated profits of $8.2 billion in 2024, and that almost a quarter of the world’s cocaine passes through Venezuela. The Maduro regime, on the other hand, maintains that “drugs are neither produced nor trafficked” in the country.

The backdrop is the so-called war on drugs, but the confrontation has marked political overtones. From underground, the opposition led by María Corinna Machado has tried to capitalize on the tensions, and Chavismo has already threatened to retaliate. “If they pressure us, we’ll pressure them,” Cabello said on Wednesday.

The clash has also triggered a chain reaction across the continent. In the last month, at least four countries with conservative governments have declared the Cartel of the Suns a terrorist organization, in a nod to the Trump administration: Ecuador, Paraguay, the Dominican Republic, and Javier Milei’s Argentina, one of its main partners in Latin America. In Spain, the ultra-conservative Vox party filed proposals in Congress and the Senate to include the cartel on the EU’s list of terrorist groups.

“We’ve seen right-wing politicians stir up the specter of Venezuela many times to gain traction,” Gunson says. “But Petro has also fallen into Trump’s trap by aligning himself with Maduro: I don’t think it’s a very smart way to score points.” Recent tensions, he says, also highlight the failure of multilateral bodies and the lack of unity in proposing solutions to the region’s hotbeds of conflict.

Aside from the political game, the risk of escalation is not entirely ruled out. “In Venezuela, this overheated rhetoric is the order of the day, but we must recognize that the situation is extremely tense,” Gunson concludes from Caracas.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.