Narco law reigns in paradise: The unsolved massacre of young people from Tlaxcala

The Oaxaca Prosecutor’s Office has focused its investigation on a ‘settling of scores.’ The lack of evidence, the involvement of the Huatulco police, and the impunity with which organized crime operates in the region underlie the case

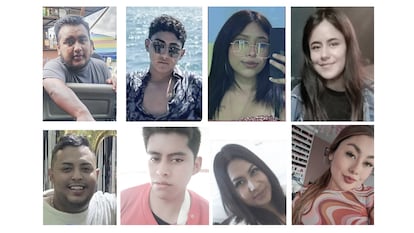

They killed Angie Pérez, 29, who had a four-year-old son. They killed Rubén Antonio Ramos, who at 24 has left his mother heartbroken. They killed Guillermo Cortés, whose family had filed a missing person report, but by the time authorities made it public, he was already dead. They killed Rolando Evaristo and Uriel Calva, whose dozens of friends said goodbye. They killed Lesly Noya, 21, athletic, smiling, nicknamed “Huesitos” by her sister. They killed the married couple Yamilet López and Raúl Emmanuel González, both 28. They killed Jacqueline Meza after her mother alerted the police that she had been kidnapped. They killed nine young women, who they took from the coast of Oaxaca, dumping them 250 miles away. They killed them all, and the authorities, who do not mourn them, dispense justice under the slogan of a “settling of scores.”

In Mexico, homicide is the leading cause of death among young people. More than heart attacks and cancer. In the first six months of 2024 alone, more than 10,000 young Mexicans were murdered. An ancient shadow hangs over the tragedy: surely they were up to something, they must have done something bad. Mexico has grown accustomed to burying its dead under suspicion. This happened a couple of weeks ago in Apizaco and its surrounding areas, in central Tlaxcala, where the group of murdered girls was from. The families were saying goodbye to them just as a rumor was spreading everywhere, a verdict meant to close the case: “They were thieves.”

The Oaxaca Prosecutor’s Office is moving along the same lines. Three weeks after the massacre, on March 19, state prosecutor Bernardo Rodríguez provided his in-depth analysis of the case: the youths were brought in by a local hotel owner to carry out robberies. This was in mid-February, and by the end of the month, they were already missing. They were found executed on March 2 in a car on the border with Puebla. A lone survivor escaped. There is one detainee (with the initials L.E.V.S., who also had a missing person’s report in his name), who was traveling with the youths and who revealed the group’s modus operandi. “They came from Tlaxcala to commit some of these acts: robbing ATMs, robbing shopping malls, robbing account holders... Not all of them, but a significant portion. There were others who came with them; we think as more of a tourist trip,” the prosecutor said. Who? How many? Does it matter?

The official spoke for seven minutes about the case — which is filed as an investigation for homicide and forced disappearance — and dedicated only a few seconds to developing the “main line of investigation”: “A settling of scores between criminal groups, the group that came from Tlaxcala, and the situation on the coast as well.” The reign of drug trafficking on the Oaxaca coast and its leader, Saúl Bogar Soto, alias “El Bogar,” identified as the main generator of violence in the state, according to documents to which this newspaper has had access, reduced to “the situation on the coast.” Woven into the fate of the youths: hotelier José Alfredo Lavariega, alias “El Jocha,” also murdered, and a municipal police force that has been questioned for years over its misconduct. EL PAÍS reconstructs the case that has uncovered the other side of paradise.

“A clear message from who really rules here”

“Huatulco? Huatulco is a very safe place, Miss. You heard about what they did to those who came from outside to steal here, didn’t you?” The old man in the sun relates details passed on to him by others who watch while selling souvenirs and floats, who saw the armed men entering the stores on the main beach in the city to pick up young people.

The bay of Santa Cruz is divided by a long pier where the twenty or so cruise ships that arrive each year moor. The water is clear and calm. Here, dozens of tourists watch the hours pass by with their feet in the sand. Most are Canadians and Americans, because this coastal town of 40,000 inhabitants and 158 hotels has direct flights to Toronto and Vancouver. Money arrives in foreign currency, and a lot of it: more than 10 billion pesos last year, according to the Oaxaca Tourism Secretariat. Amid the splashing and tour offers, there is nothing to remind us of the murdered youths, although some were kidnapped right here.

The trail of the young people goes cold on February 28. Lesly Noya changed her profile picture early that morning. Rolando Evaristo also shared his last memes before 9 a.m., posts that have now been filled with farewell messages. That day, the Huatulco police took Angie Pérez and Brenda Mariel Salas as they were leaving their accommodation, Hospedaje Jocha, according to the former’s husband, Juan Daniel Palma Chamorro. That night, they took Jacqueline Meza while she was at a beach restaurant, her mother said. One after another, the young people were kidnapped in a city riddled with cameras, home to the Secretariat of the Navy, with its 18th Naval Zone, and the Secretariat of Defense, with its 98th Infantry Battalion. “It’s a clear message from who really is in charge here,” notes a journalist from Oaxaca, who prefers not to give his name for security reasons.

The testimony of the survivor — of whom nothing is known, beyond the fact that she is still alive — is the finger pointing at the municipal corporation. But not the only one. In the last two years, the Huatulco agents had patrolled together with the marines and the commander of the unit was from the Secretariat of the Navy. In December 2024, in a letter addressed to the governor of Oaxaca, Salomón Jara, a few agents asked for help. “We are uneasy because they are going to take the marines away from us”, the letter began, “the dirty cops are happy that the navy is leaving. It is a desperate cry for help: authorities, don’t take it away from us.” With the arrival of municipal president Julio Cárdenas in January of this year, the agreement with the navy ended and the municipal police went back to patrolling alone. It was only two months before they were singled out for taking Angie and Brenda.

The police’s involvement is being investigated by the Oaxaca Prosecutor’s Office, which last week, together with the State Security Secretariat and the army, deployed a lengthy operation to verify the officers’ weapons and licenses (and also to dismantle 40 cameras that operated in the city for the criminals.) The prosecutor explained that they are seeking to verify whether any of the municipal officers’ weapons were fired and whether those cartridges match the fatal wounds suffered by the youths. This is not the first time federal forces have had to review the actions of Huatulco police officers. In September 2013, the then-director of the municipal police, Jorge Lavariega, and eight other officials were arrested for being behind a series of murders of young people.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.