‘It’s very painful because I don’t know if my son is there’: Terror at the Teuchitlán extermination center

Hundreds of people are searching among the objects found at a ranch used by the CJNG cartel for any clues about their missing loved ones. Collectives of mothers are organizing across Mexico to travel to the site

“Hello, good morning, my brother is missing. I saw a backpack like the one he was wearing the day he disappeared.” “Gray sweatshirt with the word “ocean” written on it. It’s my son. He went missing in Veracruz.” “Is there an orthopedic boot among those things, a women’s size 5?” “Can you help me? My missing relative was wearing this keychain.” “Does anyone see if there are any girl’s school shoes? My daughter disappeared five years ago.” Pain runs through these and other Facebook comments that have turned into a plea, a shared tragedy. The Guerreros Buscadores de Jalisco collective has been publishing images and videos for a week of the 493 objects they found at the Izaguirre ranch in Teuchitlán, in the Mexican state of Jalisco. Since then, hundreds of people have searched the images for clues. Teuchitlán was a recruitment and extermination center for the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), where testimonies received by the searchers indicate rape, torture and mass murder. Yet, in this country that bears the pain of 124,000 missing persons, a mother sees the photos and writes: “I wish my son were there. He disappeared 14 years ago.”

The immensity of the horror has once again gripped Mexico. It has materialized on a plot of land measuring just over half a hectare and located less than an hour from Guadalajara, the capital of Jalisco. Here, in the center of the state with the highest number of missing persons in the country (15,000 people are still missing), a group of searchers found hundreds of skeletal remains, crematoriums, graves, and a multitude of personal belongings. Some of them, like the countless piles of dusty, ownerless sneakers, are reminiscent of those found in the Holocaust extermination camps. Teuchitlán, like others before it, is the new symbol of national terror.

In a white Texas Rangers shirt, now dusty, Danny recognized his brother. Carlos Jonathan Alejandro Zúñiga disappeared in Tonalá, a municipality very close to Guadalajara, in February 2021. “A red car came and kidnapped him,” is all the neighbors told Danny: “And that he was unconscious when they took him.” He was 30 years old and had a job as an ironworker for construction companies. In these four years, Danny has discovered some information, such as that the car that kidnapped him belonged to the CJNG. Now, in addition to the baseball jersey, he has located his brother’s nickname, Guasón (Joker), in one of the notebooks that searchers found inside the ranch. In these notebooks, the cartel created groups with nicknames. Danny calls them “platoons”; his brother appears in the tenth group: “When I saw him, my skin crawled, I thought, is he alive or is he dead?” Authorities have told them they will take more DNA and clothing samples in the coming days to make matches, but that “it will take a long time”: “They say it could take years. There are thousands of missing people in Guadalajara.”

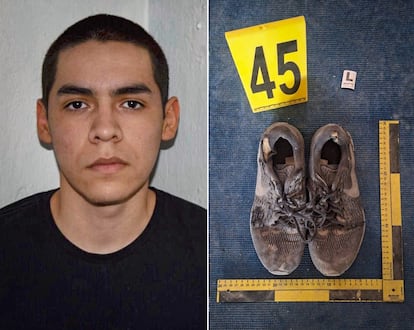

Although it has become the epicenter of horror, this isn’t a story about Jalisco. It could have been Tamaulipas, Guerrero, or Guanajuato: Teuchitlán is the mouth of a cave with thousands of underground pathways. Some lead to border states, like Nayarit, where the mother of Pablo Joaquín Gómez Orozco (17 years old when he was taken) is already preparing her trip south. Among the objects cataloged by authorities, Alejandrina Romano located a pair of sneakers that could have belonged to her son, who disappeared on March 30, 2023. The image was of focus, she says, which is why she’s going to take a look directly next week.

What makes her think her son might be there, however, isn’t the sneakers, or at least not only that. Pablo Joaquín was forcibly recruited from Tepic by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel. Alejandrina knows this because a young man recognized her son while she was putting up one of the 1,000 posters with his photo that she placed around the capital of Nayarit. “When he told me that, I froze,” she recalls. From there she knows they took him to Tala, in Jalisco, because another acquaintance saw him: “He told me they were going to recruit him, to train him, and that he would contact me at some point.” He did so on April 7, secretly. But by then he was already in Obraje, in Zacatecas. “I asked him: ‘Pablo, what are you doing there?’ ‘Ma, the Jalisco Cartel has got me.’” It had him, along with other recruits, selling drugs in a square, and then held them in “a very small place.” “They told me to go into an abandoned house at night, but they’re watching us,” she says he told her. “His voice was distressed, as if he wanted to cry.” It was the last time they spoke, and that was almost a year ago: “Now I regret not asking him more questions. At that moment, I didn’t know how to act, what to do.”

Her case involves three states, but “not one prosecutor’s office wants to take the case, not one.” “Not one in Nayarit, not one in Jalisco, not one in Zacatecas,” she laments. Nor does the Attorney General’s Office, which told her they had no evidence that her son was telling the truth. It’s a portrait of a country with a 95% impunity rate. “No one is investigating anything, and I’m desperate,” she sums up. But she continues to dig deep every day and grasps at any clue, like the one in Teuchitlán. “When I found out about the center, it was frustrating, despairing, and especially painful because I don’t know if my son is among those people.”

From Nayarit, activists are organizing collectively to charter a bus for families who believe their loved one’s belongings may be among the found items. For now there are two or three, explains Claudia Laguna, who is searching for her brother Sergio, but they hope to gather a few more and secure financial support from the State Victims Commission to be able to travel. This is a similar initiative to what is being done in Guanajuato, which shares its western border with Jalisco. “We know that many of our missing persons were taken there,” explains Viridiana Núñez, “because they received supposedly very good job offers.” The victims went off in search of these jobs, and never returned.

Her brother Pablo, a shoemaker, went missing on October 21, 2021, as he was leaving a restaurant in San Francisco del Rincón, practically on the border between the two states. They know his car left for Jalisco, guarded by two other vehicles, and then they lost track of him. She has seen a plain white T-shirt that could be his, but she shudders just thinking about it. “It would be totally heartbreaking,” she says. “On the other hand, my family and I would have a break from this constant, inconclusive mourning.”

“I want to keep searching”

Not everyone who would like to can afford the trip to Guadalajara. Francia Nazarety Borrayo, who is searching for her brothers, Brandon Yosua and Jhonns Fransua, ages 18 and 19, can’t. Neither can María del Refugio Montoya Herrera, who is still paying off the loan that allowed her to travel to the capital of Jalisco and Mexico City last year to insist that her daughter is still missing. “It’s been four years, seven months, and three days,” she says as soon as she answers the phone from Torreón, Coahuila. Her daughter, Elda Adriana Váldez Montoya, worked as a police officer for a few years until a leg injury forced her to take a sick leave. She had four children and her mother helped her out, but it wasn’t enough to support them. “We sold a refrigerator, two cell phones, and some of our things, but it wasn’t enough,” the woman says between sobs.

In the summer of 2020, Adriana accepted an offer from some acquaintances to go work in Guadalajara. “At first, she didn’t tell me where, but when I was there, she told me they took her to work at a table dance club, El Galeón, downtown, the worst part of the city.” The last time María del Refugio spoke to her daughter was on August 9 at 5:08 p.m. “She sounded sad; her leg was hurting a lot. I told her: ‘My love, come back, I’ll support you, we’ll find a way.’ ‘A few more days, Mom, just a few more days and I’ll have it.’ I haven’t heard from my daughter since then.” Since then, clues have placed her in a human trafficking ring in Guanajuato, then in Tijuana, then in Tlaxcala. The discovery of Teuchitlán now has her glued to the videos; she’s watched them all, searching: “The blue backpack resonated a lot, but no shoes, no blouse...” She’s already left a blood sample with authorities, and before hanging up the phone, she says: “I’m very much afraid that my daughter may have been there, and I want to keep searching, but at the same time, no matter what, I need to know where she is.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.