Coping with menstruation in South Sudan: ‘I miss school when I have my period – there’s no way to soak up the blood’

Cultures of shame and a lack of government support mean that women and girls – who don’t have access to feminine hygiene products – often have to miss class and work when they are menstruating

For menstruating women and girls living in developed countries, it’s not difficult to find sanitary pads or tampons. However, in the city of Bentiu, in South Sudan, tracking down feminine hygiene products is a constant struggle.

In the 11-year-old country – which gained independence from Sudan in 2011, after a long period of civil war – it’s taboo for women and girls to speak about their periods. A culture of shame surrounds the subject. Mothers generally don’t explain to their daughters how to manage menstruation, as they themselves likely didn’t receive any guidance on the subject.

In the Bentiu camp for internally displaced people (IDPs), located in the North of the country, this problem has been exacerbated by the heavy rains and horrific living conditions. More than 134,000 internally displaced people live there. Of the recent arrivals, about 90% of them lost their homes to recent floods.

Bentiu and Rubkona are the last two villages that can be reached from flooded areas. The displaced women who live there have no privacy or security. They also have no resources to manage menstruation.

“It’s been very hard for the girls and women, because we have nowhere to go,” says Nyaken Tuor, who lives in the Bentiu IDP camp, near the border with Sudan.

“Before, we used to go into the bushes to have more privacy. But since the floods, we can’t do that anymore. Instead, we have to use the latrines, which are dirty. There’s a risk of getting an infection. And in the shower, if you squat down to wash yourself during your period, you can be seen from the outside.”

Unhygienic public bathrooms in a crowded camp – which recently faced an outbreak of hepatitis E – are not safe places for girls to manage their period. But there are no other options available in the area.

At Machakos Primary School, girls like Nyasebit Mawich say they have to force themselves to wait until the end of the school day to change their sanitary pads at home.

“The bathrooms at school don’t have doors, so when you want to change your pad, people can see you. I wait until I get home to do it.”

In addition to not having doors, the bathrooms at the school are also dirty and neglected. However, even at the risk of being infected and seen, most girls continue to go to school… except during the days when they have their period.

“I miss school when I have my period because I don’t have a way to soak up the blood,” says 16-year-old Nyayiena Majiak on her first day back at the Machakos school. Many female students don’t go to class for up to five days a month, rather than risk staining their clothes and being teased incessantly.

“The children made fun of my friend so much because she got blood on herself that she dropped out of school,” adds Nyalam Koang, another student.

Lack of access to basic menstrual products and the public shaming of menstruating girls deprives many female students of access to educational opportunities. This also puts them at risk of child marriage, a major problem in South Sudan.

“Sometimes girls are teased so much [at school] that they consider getting married early so their husbands can buy them sanitary pads,” explains Peter Gatluak, 17, a student at Machakos school.

Adult women have to deal with a different kind of deprivation. When they have their period, they lose their daily income, as they don’t dare to go to work.

“When I get my period, I stop going to the shop for seven days,” explains Nyazuode Hoth, a tea shop owner in Bentiu. “I don’t make any money. But if my clients were to see me with bloodstains on my clothes, they’d stop coming.”

Ninety percent of household heads in Bentiu’s IDP camp are women, according to the UNHCR. This means that, if a woman is unable to work during her period, an entire family is at risk of going to bed on an empty stomach. Meanwhile, 80% of the female population cannot afford to purchase underwear or sanitary pads, if they are even able to find them.

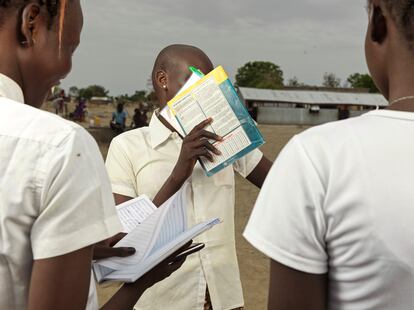

Some of the women and girls receive free sets of reusable pads from a German NGO, but they have never used them before. Nobody has ever explained the process to them, so they are left to figure it out themselves.

“When I first got my period, I was surprised, because I didn’t know anything. I just wrapped myself in clothes and didn’t tell anyone,” explains 14-year-old Bentiu Nyachot Mach. Across town, Nyaluak Gatdet, a 41-year-old restaurant owner, employs a different strategy: “I’ve found a way to roll up a piece of cloth to use as a pad. That way, I only lose three days of work,” she says.

Nyawuora Liey, 19 – who resides in the IDP camp – has another means of coping: “I layer my dresses on top of each other, so I can go to school during my period.”

Since women and girls in South Sudan generally don’t talk to each other about their period, they each find a different way of dealing with it. But, as an unwritten rule, most isolate themselves and skip their activities when they are menstruating.

“I really like going to church, but when I get my period I’m afraid of staining my clothes, so I don’t go,” says Nyachop Gatluak, a 17-year-old from Pakur, a village inundated with floodwater. “I don’t have pads and I’m embarrassed to hang my clothes outside during my period, because people will know that I’m menstruating.” By not hanging garments in the open air, there is a greater risk of infection.

Access to basic feminine hygienic products – such as underwear and sanitary pads – is the right of every woman and girl. However, in a culture of shame, with no functioning governing authority providing products, soap, adequate sanitation or health education, this fundamental human right is not being fulfilled.

However, different methods are now being tried in Bentiu to help manage the lack of resources and the taboo surrounding menstruation. Welthungerhilfe, a German NGO, has introduced a group of women to the menstrual cup. After initial reservations, most women were relieved to finally have a private way to manage their periods.

“When you hang your [reusable] pad outside, everyone knows you’re on your period… but with the menstrual cup, no one knows,” says Nyebaka Gatphan, a 25-year-old high school student who once dreaded appearing in public while having her period.

“When I wear the cup, I’m not ashamed… the blood can’t stain my clothes.”

Nyebaka’s friend, Nyekoang Malit, also started using the cup last March. She has since stopped using rags to absorb her menstrual blood. “Before, I used to cut a piece of cloth and put it in my underwear to soak up the blood… but I’m not afraid anymore.”

“I want women not to feel ashamed about menstruation, because it’s a gift from God!”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.