Trump buries the dream of a green card for 550,000 Cuban migrants

A group historically benefited by immigration laws could now begin to face difficulties finding work, legalizing their status or traveling, just like the rest of the Latino community

Castro has always been an illegal person, a fugitive from the law. Wherever he’s lived, he’s learned to live in a kind of clandestinity, because the truth is that Castro has always been wanted by authorities for deportation elsewhere. When he left Tercer Frente, in eastern Cuba, to settle in Limonar, at the other end of the country, the police turned on him for not having residency documents in the province of Matanzas. They fined him and confiscated his avocados, lemons, pigs, yogurts, and the charcoal he made with his own hands and then sold from his horse-drawn cart on the broken, municipal streets of Cuba. Now that he is in Texas, they don’t want him there either. One might think that Castro is a privileged migrant for being Cuban, one of the thousands who arrived decades ago and became residents, worked hard, acquired property, became U.S. citizens, and contributed not only with taxes, but also with a first, second, and even third generation of family members. But that’s not the case.

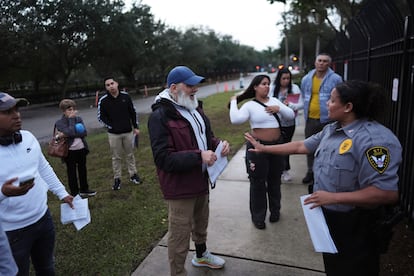

Castro sees no problem revealing his identity, albeit only his last name. He has a deportation order that was issued by a judge some time after he left Cuba, crossed Central America by himself, swam across the Rio Grande, arrived in El Paso, was detained for several months, and then released on $15,000 bail. When he went to his hearing in 2022, the judge informed him that he had missed an appointment with immigration to have his fingerprints taken. “I was shocked,” says Castro, 34. “I was never aware of that appointment.” After other failures in his immigration process, scams from lawyers, and confusion, he learned he was in danger of being returned to the island, like 42,000 other Cubans who currently remain under deportation order.

From the moment he wakes up around 8 a.m., Castro starts up his white Honda Civic and heads out to deliver food orders. Since he doesn’t have legal documents, he rents the Doordash app from an acquaintance and works as many hours as he can, because Castro doesn’t go to the movies, or to restaurants, or to parties; all he does and has done since he arrived is work. Recently, due to the announcement of a raid by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, he decided to stay home, fearing that something might happen to him. Castro lives like a specter in the world of Texans, slipping around secretly, getting by however he can, without a driver’s license, without a work permit. He never thought it would be like this, because it never was like this for his acquaintances who arrived before him, and even some who arrived after him. He believed that once he completed a year and a day in the United States, he would apply for the Cuban Adjustment Act and obtain his green card, as his fellow citizens have always done.

“But now I live here like all the people who don’t have papers,” he says.

That is to say, he lives in the shadows, in fear, like the nearly 14 million undocumented immigrants who remain in the United States today. He is one more Latino among the many Mexicans, Colombians, Venezuelans, Guatemalans and Ecuadorians who represent 84% of all illegal immigrants in the country. A group that Cubans, due to their special immigration benefits, have never felt part of. But today there are nearly 550,000 Cubans who are finding it impossible to become residents, something that used to be a relatively easy path.

Among the 681,812 Cubans who arrived in the United States between 2021 and 2024 — amid the largest exodus from the island of all time — many remain not only with I-220B status, or deportation order, but with I-220A status, a supervised release permit granted to some 400,000 Cubans randomly upon their arrival at the border, and which does not allow them to adjust their status. Added to these figures are the nearly 26,000 Cubans who arrived in the country after March 2024 and are in theory prevented from applying for residency following the revocation of protection for parole beneficiaries. Thousands have also requested refugee or political asylum status and, like migrants of other nationalities, will be affected by the pause in permanent residency processes ordered a few days ago by the Republican administration.

They are, in some ways, the new Cuban migrants, very different even from their own relatives, but very similar to undocumented immigrants from other communities. Although Cubans in South Florida overwhelmingly voted for Donald Trump, he makes no distinction in his fight to carry out the largest deportation in history. Cubans, a group historically protected by laws, could begin to face difficulties finding work, legalizing their status, traveling, or enjoying the advantages that come with not being undocumented, even though a large portion of the community can still adjust their status.

“Indeed, one could affirm that what has been happening could have a significant impact on social integration processes,” asserts the Cuban sociologist Elaine Acosta González, an associate researcher at the Cuban Research Institute who is leading a study on new migratory flows. “Our community is also being affected by a homogenizing discourse that criminalizes emigration and affects the Latino community as a whole, which includes Cubans, even though many of us do not feel part of that community, precisely because we have not gone through such complex immigration regularization processes as others. This negative environment inevitably equalizes us, or makes us in a way closer to the reality of these migrants, although we still have some comparative advantages.”

Between fear and hope for a green card

When Nasin Simón Boada, 48, arrived in El Paso, Texas, in April 2022, he was completely unbalanced, his high blood pressure worsened, and he suffered several hypoglycemic attacks. After four days in detention after surrendering to the Border Patrol, he signed the documents the authorities placed before him. “They never asked me if I was afraid to return to Cuba,” he says from his home in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. “When I left, I signed several papers. I don’t speak English, so I signed without reading them. I was desperate to get out of there.” The day he was released, he was given a document with I-220A status. He had no idea what that meant. “Initially, what I knew was that it would prevent me from being eligible for the Cuban Adjustment Act,” he says. “They could have given me parole, but it was a matter of good luck or bad luck, one thing or the other.”

Like thousands of Cubans in this same situation, Boada filed a political asylum application, which grants him the permit to work full-time in a factory. After closing his case in court, he applied for the Adjustment Act, passed by Congress in 1966 and allowing Cuban citizens to obtain permanent residency. Although some with the same status have obtained legal status, they are a tiny group compared to the thousands who have no guarantees. Boada worries every day. When he goes out, he carries all his documents in order. He even carries a letter in English, in case a problem arises and he has to explain his case to the authorities and explain that he is an immigrant with permission to remain in the country. “I don’t feel completely safe, but it’s what I can do right now,” he says.

Viviana’s parents — she asked to change her name for security reasons — are the latest Cubans to be harmed by the Trump era. She is 66, he is 69. Near the end of their lives, they left their farm in Sancti Spíritus to join their daughter in Miami. They never considered emigrating, but in early 2023, the Joe Biden administration opened the humanitarian parole program to Cubans, a legal, fast, safe, and inexpensive way for 111,000 Cubans to reach the United States. Less than a year has passed since they arrived, since they met their granddaughters. They never imagined this scenario in which, in less than a month, Trump would declare them illegal like so many others. “We never thought this would affect parole,” says Viviana. “We thought they would be able to benefit from the Cuban Adjustment Act, not that they would be in immigration limbo.”

They never suspected a thing because even their family, who had settled in Miami before them, assured them that Trump was the best option for everyone, that he would lower gas prices and improve the economy. “It was very contradictory; we were afraid, and yet our closest family supported this person who made us feel fear,” the daughter says. “My dad’s brother and his entire family, or my mom’s cousins, they all had the same narrative that we just had to live through a Trump administration to know what it was like to live in a prosperous United States. But even so, without having had any precedents, we knew that with emigration it would be hard, although never at the levels it has reached.”

Viviana’s parents have been advised to apply for political asylum, now that their work permits and any other benefits are also expiring, but their daughter refuses, fearing she might be committing fraud. “All Cubans can claim problems in Cuba, but on what basis? What evidence? What arguments? So I don’t plan to do it, nor do I have the $4,000 that lawyers charge. It’s a risk we’re going to take.”

Of all the Cubans who have emigrated in recent years, those who entered using the CBP One app appear to be safer. Darién Álvarez, 30, who arrived in the country less than a year ago after waiting for his appointment in Hidalgo, Mexico, was “lucky” unlike some of his acquaintances, who were left behind once Trump took office and eliminated, on his first day as president, the tool Biden had used to alleviate the border crisis. He now has a work permit and a driver’s license, and will apply for the Cuban Adjustment Act when he completes one year and one day of legal stay in the United States.

“I’m doing pretty well because I applied for asylum, and in a year and one day I’m going to apply for residency, because that’s my right,” says the young man, who works at a painting company in West Palm Beach. Although everything seems to be going well with his process, he can’t deny that he sometimes feels scared, even more so when a new measure against migrants is enacted. That’s why he never liked Trump. “I didn’t want him to win,” he says. “He announced the things he was going to do, and now he’s doing them. Many people thought about the price of gasoline, but no one thought about the problems it brings to many families who had to start from scratch to come here in search of an opportunity that isn’t being offered to them now either.”

Despite the different categories that keep thousands of Cubans in legal limbo, immigration attorney Willy Allen believes those most at risk are those with I-220B status. “These people never had legal entry, so they couldn’t legalize themselves. I suspect this year will be very hard for them,” says the attorney, who nonetheless remains hopeful that those with I-220A status can adjust their status, especially given that so many South Florida politicians have taken up these cases. “My suspicion is that this year may be favorable for them because a federal court has arguments scheduled for September. The I-220A status was used at the border haphazardly. So the inconsistency with which it has been applied provides a much stronger guarantee.” Furthermore, Allen recommends that Cubans who entered with the CBP One application and humanitarian parole apply for political asylum as soon as possible.

Although, among all communities, Cubans continue to enjoy certain immigration privileges, fear has also taken hold of this group for the first time. “There is a growing sense of fear in our community, of hopelessness, of concern, of greater anguish,” says Cuban sociologist Elaine Acosta. “It’s a process that other migrant communities of Latin American origin have experienced for many years, and one that we had not experienced before.” However, the researcher says that, according to the study she is conducting, she has noticed that despite the legal limbo in the community, “there is a kind of denial of what is happening.” “I think there is still hope that we will receive differential treatment, like we have enjoyed previously. However, we often lack the legal literacy or political awareness necessary to understand the seriousness of the issue and the consequences it will have.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.