The American cultural boom a century on: Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos and Louis Armstrong

1925 was a remarkable year for the American novel as great titles renewed the art of storytelling and had the power to influence upcoming writers for decades to come

In George Steiner’s first book, Tolstoy or Dostoevsky, Steiner promotes the theory that the two great literary traditions of the 19th century – the golden age of the genre – had nowhere left to go: the European in general and the Russian in particular. With Flaubert, Balzac, Dickens, Zola, Stendhal, Turgenev, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, a point of perfection had been reached, but also of saturation. How to continue with a universal vision? Steiner asks himself. He finds the answer on the other side of the Atlantic with the explosion of North American literature.

Steiner does not indicate a specific starting point, but it could be said that the foundational moment coincides with the death of Edgar Allan Poe, in 1849. The following five years witnessed an outpouring of collective talent that would lay the foundations for the literary future of the then democratic and still young American nation. The big bang came at the midpoint of the century, between 1850 and 1855, when the formidable figures of Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Thoreau and Walt Whitman published works whose influence lives on today.

To these authors we must add Emily Dickinson, who secretly wrote poems of a caliber comparable to those of Whitman. Amazingly, during that prodigious five-year period, Moby Dick, The Scarlet Letter, Walden: or Life in the Woods and Leaves of Grass were published, as well as Emerson’s Representative Men. Thus began a dizzying journey through the literary cosmos that would not be matched until exactly a century ago, in 1925, commonly considered the annus mirabilis of American literary history.

Focusing on novels alone, that year saw the publication of four titles of great historical resonance: An American Tragedy, by Theodore Dreiser; The Making of Americans, by Gertrude Stein; Manhattan Transfer, by John Dos Passos, and The Great Gatsby, by Francis Scott Fitzgerald. To these should be added In Our Time, Ernest Hemingway’s first collection of short stories. Also in 1925, William Faulkner received the news that a New York publisher had accepted the manuscript of his first novel, Soldiers’ Pay. But that was not all: further enriching the year’s extraordinary literary harvest was In the American Grain, a collection of essays in which William Carlos Williams examines fundamental aspects of his country’s history and literature.

In poetry — a discipline that always exerts a determining influence on avant-garde prose — the enigmatic E. E. Cummings published XLI Poems, and H. D. her Collected Poems. That year, the two major poets of Anglo-American modernism also published works that offered a glimpse of the magnitude of their future contributions, T. S. Eliot the selection entitled Poems 1909-1925, and Ezra Pound the inaugural segment of The Cantos.

Returning to the novel during that year, it is important to introduce some nuance. With An American Tragedy, Dreiser took the tradition of naturalism inherited from Émile Zola and ran with it. Over 800 pages, the author fictionalized the story of the murder of Grace Brown by Chester Gillette, who was sentenced to death and executed in the electric chair in a case that aroused unusual interest in the press at the time. The novel is a tragedy that caused a sensation for its psychological depth and its approach to the facts, transforming them into a profound aesthetic experience. Contemporary critics affirmed that it was the worst written American novel of all time, but the strength with which Dreiser narrates the nuances of the tragedy compensates for the stylistic defects, otherwise undeniable. The novel is unreadable today.

Even more unreadable, if possible, is The Making of Americans, a narrative of almost 1,000 pages in which Gertrude Stein seeks to transfer the findings of Cubism into literature, telling the story of her ancestors in an experimental vein, based on insufferable repetitions. When a critic as shrewd as Janet Malcolm made the firm resolution to read it decades later, she was forced to literally cut it up to try to make it digestible, failing in the endeavor.

Without denying its reputation of being the least read novel of all time, Edmund Wilson said of The Making of Americans that, behind its impenetrability, there were valuable gems that justified taking up the challenge, something that countless generations of writers have done and continue to do, even in a fragmentary way. Based in Paris for many years, Stein was a friend and mentor of figures such as Picasso, Matisse, Hemingway, Blaise Cendrars, Thornton Wilder and Fitzgerald. Her influence has more to do with the force of her personality than with her literary work, though she racked up some memorable achievements, most notably the masterful Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.

Manhattan Transfer, by John Dos Passos, who Jean Paul Sartre once said was the best American novelist of his time, has not aged well either. The novel mixes cinematic montage with journalese, a lesson learned directly from James Joyce. It is extremely interesting that three of the supposedly four “great American novels” of 1925 are of archeological interest today. This reflects Ezra Pound’s idea that the history of literature should be told like that of scientific advances, according to the contributions that renew the art of narration.

The case of The Great Gatsby is very different. When it was published, it went relatively unnoticed and the reviews it received were mostly indifferent or hostile, with a few notable exceptions. One hundred years after its publication, Fitzgerald’s novel not only retains its freshness, but is considered one of the most perfect narratives ever to come out of his country. Edmund Wilson was one of the first to point out its greatness, and T.S. Eliot said of it that “It seems to me to be the first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James…”

The novel tells the story of Jay Gatsby, a millionaire who makes his fortune by bootlegging alcohol during the Prohibition. The novel’s portrayal of the jazz era is unparalleled. In the background, a tragic love story unfolds, narrated by the endearing Nick Carraway. Set between New York and Long Island during the roaring 1920s, the narrative demonstrates absolute technical mastery and emotional depth. In addition to several film versions, the novel has been echoed in works by Raymond Chandler, Philip Roth, Ross MacDonald and Spanish-speaking authors Ernesto Quiñones and Hernán Díaz.

The other valid narrative lesson of 1925 is given by Hemingway in his first short stories, which, as in the case of Fitzgerald’s novel, can be said to be an example of literary perfection. His influence on future generations is incalculable and reaches a long list of short story masters, such as Raymond Carver, Richard Ford, Denis Johnson and, because of the spare, conciseness of his prose, the novels of Cormac McCarthy.

The historical importance of 1925 is highlighted by the formidable zigzagging of forces that took place between the three major narrators of the period. The American narrative genome is the result of two extraordinarily fertile frictions: on the one hand, that between the slender elegance of Fitzgerald and the subtle austere prose of Hemingway, and on the other, that of the baroque style of Faulkner, whose name first appears at that time, and Hemingway’s containment. Cormac McCarthy is heir to both.

Although extraordinarily rich and diverse, the panorama outlined so far is incomplete. There are many more titles and authors of note, some of which have faded into oblivion, while others have managed to maintain our interest in one way or another. In 1925, novels were published by Willa Cather, Sinclair Lewis, Edith Wharton and Sherwood Anderson. One work that is still unusually alive is Anita Loos’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, of which there was a musical and several film versions, one of them starring Marilyn Monroe.

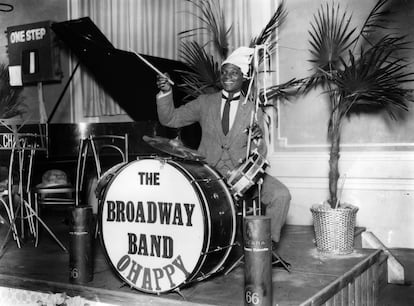

Being bang in the middle of the jazz era, 1925 takes us to the very heart of Black culture. Among the seminal titles published that year is Alain LeRoy Locke’s anthology The New Negro, which heralds a culturally crucial event, the Harlem Renaissance, which involved writers, artists and activists of the highest caliber, including Duke Ellington, W. E. B. Du Bois, Aaron Douglas, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, Jean Toomer and Claude McKay.

An iconic publication of the era was The Book of American Negro Spirituals, edited by James Weldon Johnson. In 1925, Louis Armstrong recorded his first jazz quintet, the first Texas blues recordings were made, and New York blues recordings reached the top of the charts. In music, George Gershwin and Aaron Copland were in full swing, as were Edward Hopper and African-Americans Aaron Douglas, Augusta Savage and Archibald Motley in the art world, the latter associated with the Harlem and Jazz Renaissance. The excellent writer Adela Nora Rogers St. Johns kicks off the Hollywood novel genre with The Skyrocket.

An anecdote with more significance than one might at first think is that 1925 saw the inauguration of an essential element of future road novels penned by Nabokov, Sam Shepard and Jack Kerouac and the beatniks: the country’s first motel in San Luis Obispo, California.

And one of the major events that year whose importance cannot be overstated was the founding of The New Yorker on February 17, the best literary magazine of all time and a true showcase of American literature including masterly profiles, poetry, caricature, cultural criticism in all its guises and fiction signed by some of the most important names in world literature.

Important as it is, The New Yorker is but a small part of the story. If anything reverberates strongly a century later, it is the importance of the cultural legacy of African-Americans, literary as well as artistic and musical.

While the works of Dos Passos, Dreiser and Stein have struggled to remain relevant, those of African-Americans are filling our bookshops. There is no direct line connecting them to what happened the year The Great Gatsby was published, but a century later some of the most prominent names on the literary scene are African-American: Ta-Nehisi Coates, Kevin Young, Colson Whitehead, Jesmyn Ward, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Roxane Gay. One of the effects of their contribution is a shakeup of the rules.

Without getting too woke, it must be said that The Great Gatsby contains some problematic elements, and its world is exclusively white. None of this is to detract from its greatness, of course, but some things needed to change. The much maligned as well as brilliant Hemingway, prototype of the alpha male writer, once said that the history of the American novel began with the publication of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. True enough. Significantly, the most recent National Book Award-winning novel is James, in which African-American writer Percival Everett rewrites Twain’s work from the perspective of his Black protagonist, expunging it of its most problematic aspects without detracting one iota from its literary merit.

Many things have changed in American culture in the last 100 years, including how we understand literature, but what is perhaps most notable is something that Norman Mailer and more recently Timothy Snyder once complained of: in today’s America, the democratic spirit represented by such emblematic figures as Walt Whitman and Thoreau is conspicuously absent.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.