How the Russian meddling machine won the online battle of the illegal referendum

The Spanish government and public media outlets did not react in time in the face of a network of fake news stories and social media posts

Lacking the resources necessary to be able to achieve their objective of breaking away from Spain, pro-independence forces in Catalonia put their messages and fake news at the service of a pro-Russian meddling machine, which amplified them via thousands of profiles on the social networks with links to the Kremlin and Venezuelan chavismo, with activists such as WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange acting as links in the misinformation chain. According to a number of studies about the social conversation on the internet, this conscious strategy swayed international public opinion, given that it received no kind of resistance on the part of the institutions of the Spanish state.

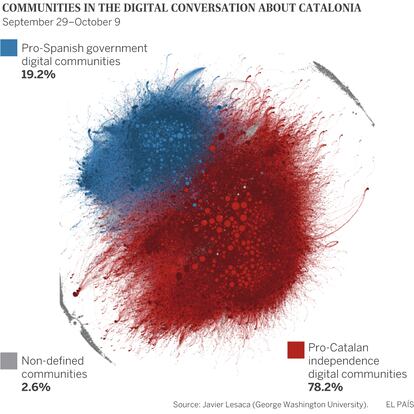

Neither the government, nor the political parties nor public media outlets responded in an organized manner to the attack against them on social networks. One part of the evidence: according to an analysis carried out by George Washington University of the social conversation that took place in the days prior and subsequent to the referendum of October 1, two narratives were created. Some 78.2% of messages defended the independence of Catalonia and portrayed the Spanish state as repressive for encouraging police brutality. Meanwhile, 19.2% defended the legitimacy of the Spanish state in terms of being able to stop the referendum from going ahead given that it was unconstitutional.

In this study, to which EL PAÍS has had access, an advanced software program that uses Spanish technology was used to measure and analyze big data. The author of the study, Javier Lesaca, is a visiting scholar at the School of Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University. He has analyzed a total of 5,029,877 messages from Twitter, Facebook and other social networks that were posted between September 29 and October 5.

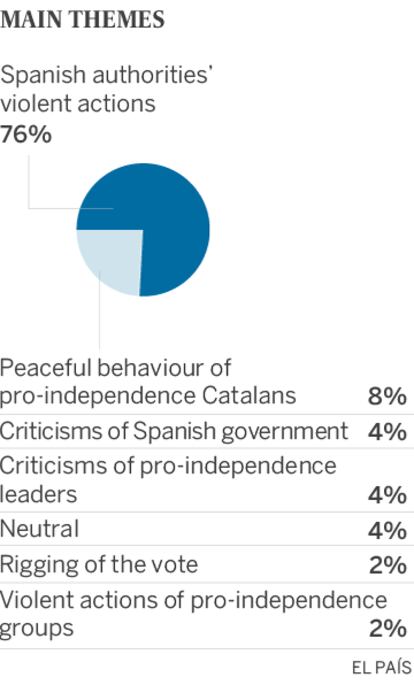

The main conclusion: “The real battle that was fought on October 1 in Catalonia occurred in the field of public opinion. The communication plan developed by the organizers of the referendum was a success.” The proof is that the “dominant message among global public opinion on October 1 was the one that suited the pro-independence forces, of Spanish police who acted with violence against peaceful Catalan citizens who wanted to express their opinion in a democratic way at the polls. The narrative and the images in favor of the government or against the celebration of the referendum did not manage to dominate nor attract the interest of the digital conversation.”

In terms of volume, and focusing just on the 50 most popular stories, pro-independence messages were shared 966,132 times, while those favorable to the strategy of the government were shared just 47,321 times. A meager 4% of those messages criticized the organizers of the referendum, which had been declared illegal in advance, while 2% gave examples of fraud such as photos of people voting at more than one polling station.

Focusing on links to media outlets, the total number of those pointing to Russian state media sites RT and Sputnik exceeded those of global names such as CNN and The Guardian, and even to Spanish dailies such as El Mundo and La Vanguardia. What’s more, the resistance that public Spanish media put up was non-existent. The combined messages of the two Russian state outlets had 10 times more influence on the social networks than those of the two public Spanish media analyzed by this report, RTVE and EFE, whose influence was merely token.

Another recent analysis, from The Integrity Initiative group, which is dedicated to combating Russian disinformation in Europe, says that “the Kremlin is seeking influence over Madrid.” It continues: “What we have detected is a classic control and absorption mechanism of the KGB. By supporting both sides, Russia is in the position of trying to avoid that the Catalan independence crisis advances down an unwanted route or gets out of the control of Moscow,” explains the report, entitled ‘The context of Russian interference in the Catalan question.’

This would explain what Vladimir Putin himself said in a speech given on October 19, when he stated that what is happening in Catalonia is “an internal matter for Spain and should be solved according to Spanish laws and in accordance with democratic traditions.” The analysis of The Integrity Initiative does not believe that there is any contradiction between the words of Putin and messages related to Catalan independence in media financed by the Kremlin. Simply put, Russia is seeking to hold an advantage by playing both sides of the game.

What’s more, the institute points to the real objective of Moscow being the fostering of a resurgence of the far right in Spain. According to the report: “Far-right voters and conservatives who are disappointed by the PP [the governing conservative Popular Party, led by Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy], are showing a growing sympathy to the Russia of Putin. While that sector is not still politically relevant, the rise in Spanish nationalism as a reaction to the Catalan issue will probably trigger the growth of parties such as VOX,” it states, in reference to a right-wing party that was created by former members of the PP, and which opposes Basque and Catalan independence and wants to see a more centralized Spanish state.

It is here where one of the more common obsessions of the pro-Russian networks and its populist allies in the East of Europe appears: George Soros, the magnate born in Hungary, a survivor of the Holocaust, and who is committed to a number of progressive causes. A number of minority media outlets linked to Russia, such as El Espía Digital, which published stories from RT and Sputnik, have published stories that state, with no convincing proof, that Soros is financing Catalan independence.

Whatever the case, the pro-independence campaign on the internet is organized and is not making use of just the voluntary activity of supporters online. That is shown, according to the analysis by Lesaca at George Washington, by the fact that the messages from RT and Sputnik were shared on the social networks by profiles that, in 87% of cases, could be defined as false or automated, activated and controlled by a higher authority. In this task they were helped by chavista networks in Venezuela, which also contain automated profiles to a great degree. The large majority of these messages were clearly damaging to the strategy agreed by the Spanish government with the opposition.

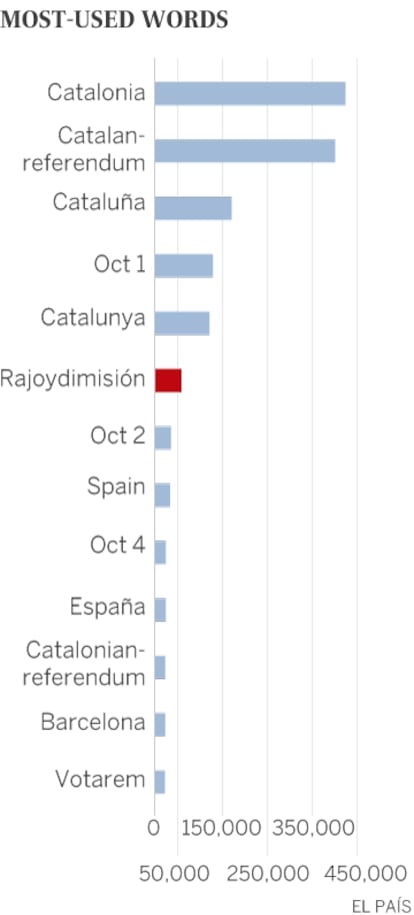

Another indication: the sixth most-used term in the conversation of social networks in the days prior and subsequent to the referendum on October 1 was #RajoyDimision (Rajoy should resign). According to this analysis, “the introduction of this element among the most popular terms suggest the hypothesis that, in a deliberate strategy, various groups or individuals were interested in associating the crisis in Catalonia with the image of the prime minister of the government.”

Legitimizing Crimea

An opportunity that the Russian machinery detected in the pro-Catalan independence drive was that of trying to give legitimacy to the independence that would benefit the Kremlin – that’s to say, the annexation of the Crimean peninsula and the Donbass during the Ukrainian conflict of 2014. As has been confirmed by the researcher Donara Barojan, from the Atlantic Council, “the separatist media in the east of Ukraine tried to use the Catalan crisis as a way to legitimize the illegal annexation of Crimea.”

Barojan, in an analysis from the Digital Forensics Lab, explains that this is not the first time that something like this has happened. The pro-Russian media in Ukraine already interpreted the Scottish independence referendum of 2014, in which the no vote won, in the same way. Whatever the case, the Kremlin has taken advantage of the crisis. According to Barjoan, the Catalan crisis has allowed for “a resurgence of the Russians’ arguments and of the separatist leaders who started to use them in the 2014 crisis.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.