Last gasp for Spain’s tobacco industry

Over the last 15 years, manufacturer Altadis has closed down all but one of its factories

When she first started work at the Fábrica de Tabacos in 1974, at the age of 18, Montserrat Martínez found the smell of the piles of tobacco leaves unbearable. But in time, she explains, she learned to live with it, going on to work at the cigarette factory in Logroño, in the small northern region of La Rioja, until she took early retirement in 2015, aged 58. After a working life spent in the plant, she says she was shocked when the owner, Altadis, announced last week that it was closing down its operations there, and she burst into tears.

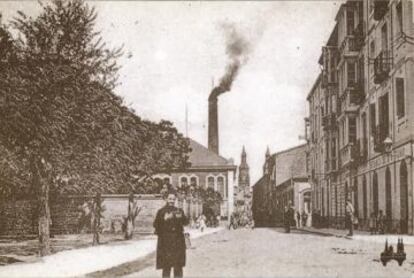

The plant was opened in 1890 and was the first major industry in La Rioja

The reasons for her emotional reaction are many: firstly, because she is the third generation in her family to have worked at the factory; her grandfather was first, and her youngest sister the last, along with her uncle, her brother, and her brother-in-law. Secondly, it’s a matter of regional identity: the plant was opened in 1890 and was the first major industry in La Rioja. With its closure, hundreds of jobs will be lost. Montserrat also admits to identifying with the legendary status of the cigarette maker, personified by Carmen, the fiery character in Bizet’s opera of the same name, and a powerful symbol of women’s fight for their rights during the industrial revolution.

Montserrat, her family, and the factory illustrate the continuing decline of Spain’s tobacco industry, which a century ago contributed around 16 percent of the country’s GDP. Today, that figure has fallen to one percent, the overwhelming majority coming from heavy sales taxes.

Altadis was created out of the merger between Spain’s former tobacco monopoly Tabacalera – which dates back to the 17th century – and its French counterpart Seita in 1999. Since then, one by one, it has closed down almost all of its 12 factories, leaving just the cigarette factory in La Rioja, which makes the Fortuna and Ducados brands. The company will leave just one plant open, in Santander, which makes cigars.

Changing habits and a product that is a serious danger to health lie at the root of the decline of Altadis. In the early 1980s, 40 percent of Spaniards were smokers; that figure has fallen to 24 percent. Profits have been hit as the cost of cigarettes has steadily risen, coupled with the problem of contraband tobacco. In short, cigarette sales have fallen by almost 50 percent in the last five years.

Neither the subsidies offered by the Industry Ministry, nor pressure from the regional government of La Rioja, nor protests by the workforce, which insists that the factory could make a profit from supplying the Spanish market, have been able to persuade Altadis, which owns Britain’s Imperial Tobacco, to reconsider its decision to close the plant in June.

One by one, Altadis has closed down almost all of its 12 factories, leaving just the cigarette factory in La Rioja

“Fortunately for me, I am of an age to take early retirement, but a lot of young people will lose their jobs, many of them have children and mortgages and no way to make ends meet,” says Montserrat’s sister Magdalena. Of the factory’s 471 full-time employees, 180 aged 51 or over will be given early retirement; the rest will be laid off.

One employee, who doesn’t want to give his name, says that he turned down a job three years ago after being told by Altadis the company had a future. “We feel like we’ve been tricked; right up until the announcement, they were telling us that everything would be okay: measures were being taken to improve productivity and they were going to ask the regional government for help,” says Pedro Ibarra, a 38-year-old father of a young child. “We have done everything to try to make this factory profitable,” he says, citing the 80-strong security and cleaning team, the truckers who moved the tobacco, and the drivers who bused the workforce in each day.

The current factory is some 18 kilometers outside Logroño, but Montserrat, her sister, and their friend Nati Alcalde all started at the original plant, built in 1890 in the center of the city, and that is now occupied by library and regional parliament. Last week the three visited the old factory, remembering their time there: part of the manufacturing process was still carried out by hand; how the female workforce would rush to the windows when conscripts marched past on their way to and from their barracks, how jobs were passed down through families; how most of the machines were managed by women, a tradition dating back to the beginnings of cigarette manufacturing, supposedly based on women’s superior manual dexterity. The three also discussed the closure of the factory and the end of an era. “I should stop smoking,” says Montserrat. “I’m going to try when I retire,” adds her sister.

Third and final move

David Eive is now 38, and is the third generation of his family to work in the cigarette industry. He started at the age of 22 at a Tabacalera plant in A Coruña, following his mother and great aunt, believing he would be with the company his entire working life. Now he’s not so sure. In 2003, when the plant in the northwestern region of Galicia closed, he was offered a job at another factory, and he chose Alicante, where he went with his girlfriend. “It was newly opened, and so I thought it would have a better future. I was wrong,” he says.

The Alicante factory closed down, and in 2009 he moved with his wife to Logroño, leaving a half-paid mortgage behind. His son was born in La Rioja, and two months later he bought a house. “I don’t know what I’m going to do. If they offered me the chance to go to Santander [Altadis’ last factory in Spain], which I don’t think they will, I’d go.”

There are people working at the La Rioja plant from all over Spain, transferred here as Altadis’ closed down its other factories around the country over the last 15 years.

Óscar Pita has taken the same route as Eive, from A Coruña to Logroño, by way of Alicante. At 51, he looks set to be given early retirement.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.