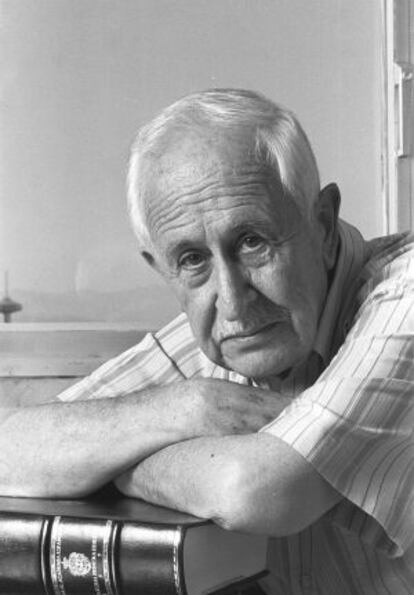

José Luis Pinillos, mentor of academic psychology in Spain

Winner of the Prince of Asturias Prize for Social Sciences dies in his nineties

José Luis Pinillos, considered the principal disseminator of academic psychology in Spain, died last Monday in Madrid. He was married to Elvira Laffon, who was linked to the famous Instituto Libre de Enseñanza school-teaching organization. Born in Bilbao in 1919 to a well-to-do family, Pinillos finished his studies in 1936 just as the Civil War broke out, and he enlisted for Franco, ending the war as a lieutenant, then enlisting again in the Blue Division, to fight the Soviets in Russia under German orders.

Back in Spain, he survived for a while on a small allowance from his grandmother and writing occasional articles as an art critic. Then in Zaragoza and later in Madrid he began his studies in philosophy, with a thesis on The concept of wisdom in St Thomas. Oriented toward thought and metaphysics, he went to Germany and the University of Bonn, entering Hans Gruhle's Institute of Psychology. Gruhle persuaded him to go on to England and the school of Hans Eysenck. Later in Madrid he entered the National Research Council (CSIC), editing the in-house organ, Arbor, and organizing the School of Applied Psychology, the first Spanish institution to impart a specific study plan in this discipline.

A brief stay at the University of Caracas ended in a brush with the Venezuelan regime, and he returned to Madrid, obtaining the chair of general psychology at the University of Valencia, though most of his teaching career was spent at Madrid's Complutense, whose chair of psychology Pinillos obtained in 1968. Psychology then came under the Faculty of Philosophy, but by 1980 was granted a faculty of its own. Dating from this period is a famous remark of his: "In this epoch, in philosophy, you can only be a Marxist or an idiot, and I am not a Marxist."

In philosophy, you can only be a Marxist or an idiot, and I am not a Marxist"

Heir to the tradition begun in 1879 by Wilhelm Wundt, father of experimental psychology, Pinillos was armed with a broad erudition in philosophy, science, literature and art, something that those who knew him found extraordinary.

Thanks to his celebrity and articulate penmanship, many of his numerous books sold very well, particularly his Introducción a la psicología (Or, Introduction to psychology), a manual which for generations of students would constitute their first encounter with the subject, its most recent (24th) printing being in 2010. Another book which popularized the subject was La mente humana (or, The human mind). Pinillos has been defined as a humanist psychologist, though he did not much care for the term. In ideological terms, he described himself as a liberal conservative.

In the political field, particularly in the waning years of the Franco regime, he enjoyed an aura of authority, and occasionally used it. At a speech in the Madrid Chamber of Commerce, apropos of political change, he remarked: "As long as the stalled motor remains in this state, there will be no change at all," and turning to the government delegate then present, added: "I speak in the Aristotelic sense, of course."

On another occasion, that of the attempted coup in 1981, when the whole Cabinet was being held hostage in the Congress house by rebellious civil guards, the provisional government of under-secretaries called him to ask how best to go about talking down the coup-leading colonel, Antonio Tejero. Pinillos said he was busy at home with an infirm relative.

"What should we do?" they asked. Pinillos advised: "I think you should not attempt to assault the place; this would enrage the occupiers. I think you should go little by little, supplying them with a trickle of information to the effect that the coup has failed and that nobody is supporting it, which will in the end demoralize them."

Also famous were his standard psychological test, his work on training and selection of company personnel, and his work for the Traffic Department, the air force and NATO, often involving applied statistics. He was receptive to psychoanalysis. Many chairs of psychology in Spain were awarded by panels that he presided. The Spanish Academy of Psychology owes to him much of its academic and social prestige.

Pinillos was described as a Humanist psychologist, but he disliked the term

He became a member of the Royal Academy in 1988, having won the Prince of Asturias Prize for Social Sciences and Humanities in 1986. He was also much cherished in academic circles throughout Latin America. Having retired in 1986, he turned to the study of post-modernity, publishing El corazón del laberinto (Or, The heart of the labyrinth), a chronicle of "the end of an epoch." He published many newspaper and magazine articles, particularly in the conservative Abc. A man of talent, lucid and amusing and an exceptional teacher, he possessed a humanistic authority which, in the conservative media, was often compared to that of Gregorio Marañón and José Ortega y Gasset.