Documenting an artistic partnership

An upcoming exhibition at the Thyssen examines the detailed notes that Edward Hopper and his wife, Josephine Nivison, kept on the painter’s work

This is the story of a married couple. It is also the story of some accounting books. Finally, it is the involuntary biography of a relationship that was as close as it was troubled.

From the time of their wedding, in 1924, Edward Hopper and his wife, Josephine Nivison, methodically noted down all the details about each one of the works created by the great American painter until his death in 1967. It was a natural thing for them to do: they were simply following the advice — the precepts, almost — of Robert Henri, their teacher at the New York Art School. Henri encouraged his students to freely develop creative expression, but also to rigorously promote and manage their own careers.

The three ledger books they left behind — there is a fourth one but all it contains are random notes — feature a handwritten title on the cover that simply reads: “Edward Hopper: his work.” Originally, the idea was to describe each painting: the composition, the colors, the format, the materials and information about the sale, including the price, date and buyer’s name. Each entry was carefully written in by Jo — that’s what her husband called her. She also drew a box that Edward filled in with a small sketch of the painting in question.

But the collaborative project also reflected many of their individual traits. Edward Hopper was a tall, quiet man, known for his long silences, his thoughtful personality and his cultivated manner. Jo was talkative, resourceful, occasionally naïve and very careful about her own appearance. Her dress style was neat and sober, yet she radiated vitality and conserved a halo of youthfulness well into her eighties.

The idea was to describe composition, colors, format and materials

Deborah Lyons, former curator at the Whitney Museum in New York and author of the book Edward Hopper. A Journal of his Work (now out in Spanish), which contains a selection of pages from all three ledger books, says that there was a “good Jo” and a “bad Jo.” The good one was Hopper’s artistic accomplice. The bad one made nasty comments in her letters and diaries. The author also included testimony by one of the couple’s friends, who said that every time he saw them quarreling, it looked like they were on the verge of divorce.

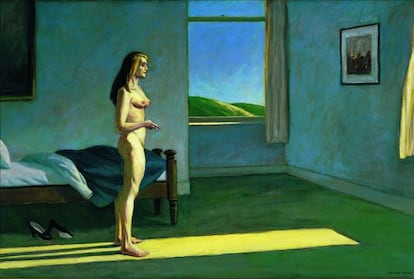

They seemed incompatible, yet they were inseparable. Josephine was very proud of being in control of her husband’s career. She was also the only model he ever used in his numerous paintings of female characters. Maybe it was a matter of jealousy, or just because it was easier to use her since she was always around. Even when he transformed her into different canvas characters, including a prostitute, she always made sure that he included a dedication (“To my wife, Jo”) to dispel any suspicion of infidelity.

In her notes, Josephine often made comments that went beyond the strictly descriptive. Sometimes they were openly critical, and occasionally contained circumstantial details: “Too much lipstick,” she wrote about one of her husband’s imaginary women. In Hotel by a Railroad, the description ends with this comment: “The woman should pay more attention to her husband than to the tracks under the window.”

Hopper barely wrote anything in these books, which are dated 1924, 1932 and 1943. At first the sketches of the paintings were really small, almost as if they were made out of obligation. As the years go by, however, they became increasingly elaborate. The task of reproducing his own paintings became another one of the steps required to complete the artwork. The Spanish edition of Lyons’ book includes reproductions of the final paintings next to the small ink sketches.

Josephine often made comments that went beyond the strictly descriptive

The ledger books not only provide valuable information about Hopper’s work and career. Jo’s vivacious comments and the details she provides (such as the fact that the woman in the famous Hotel by a Railroad painting is reading a diary, not a letter with bad news, as some supposed) help us to understand his work better. After the artist’s death, his wife donated the books to the Whitney Museum, which owns 2,500 artworks by Hopper. Many of those were also donated by Josephine, who only survived her husband by one year.

The funny thing is that the Whitney’s Hopper collection includes another little notebook written exclusively by Edward Hopper, in which he kept track of every one of his paintings from his first sale in 1913 to his last in 1967, two months before his death. There are no illustrations, just written text. Why the double accounting, one collective and the other individual? It has often been said that Hopper is the painter of solitude in modern city life. Perhaps he wanted to preserve that small parcel of intimacy with regard to his own work. Both this precious book and the major exhibition due to open on June 12 at the Thyssen-Bornemisza will allow Spanish museum-goers to learn more about the fascinating world of this melancholic painter.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.