Werner Herzog, the filmmaker of the cosmos, beauty and truth

The winner of the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the latest Venice Film Festival presents his seventh book, ‘The Future of Truth’

For the filmmaker Werner Herzog, 83, the truth that matters transcends mere fact. Starting in the 1990s, he began using a term he coined himself: ecstatic truth, which refers to poetic truth, emotional truth, a stylized truth that illuminates and moves. “It’s not about delivering fake news, but about delivering beautiful news,” he vigorously clarified before the packed auditorium of New York’s 92NY cultural center, where he was presenting his seventh book, The Future of Truth.

He gave as an example the quote at the beginning of his documentary Lessons of Darkness (1992): “The collapse of the stellar universe will occur — like creation — in grandiose splendor,” which he attributed to the philosopher Blaise Pascal. “The quote was entirely my own invention. Honestly, I don’t think Pascal could have said it better, but it allowed me to take the viewers from a heightened state and keep them there throughout the documentary.”

For the director, truth is a construct for coping with daily life, and since we need beauty more than ever, it’s up to us to transform it into a glorious experience.

Herzog has had a prolific career, covering subjects as disparate as they are intriguing. He has devoted films to portraying figures as mysterious as Nosferatu or Kaspar Hauser. He has shot documentaries about volcanoes, a man’s obsession with the brown bears of Alaska, the devastation of Kuwait after the First Gulf War, death-row killers, Gorbachev, cave paintings, Antarctica, and the impact of meteorites, among others.

Ghost Elephants, which will premiere in March 2026 on Disney+, follows South African explorer Steve Boyes in Angola as he tries to determine whether a species of giant elephants unknown to humans exists. Herzog’s curiosity knows no bounds. The director — who, in addition to making more than 70 films, has acted in and directed more than 20 operas — confesses that he also would have liked to have been an athlete, a mathematician, or a chef.

He has made more documentaries than fiction films, not so much out of preference as due to financing difficulties. For him, the key is to keep creating without waiting for idyllic conditions. “If you don’t understand the rules of cinema, you’re not only wasting your time, but your life,” says the director, who won the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at this year’s Venice Film Festival. His best advice for new generations is: “Do it anyway.” A defender of practice over theory, the director founded his own film school, Rogue Film School, through which he offers seminars and film-acceleration workshops where about 50 filmmakers from different countries commit to shooting and editing a short film in nine days and showing it on the last.

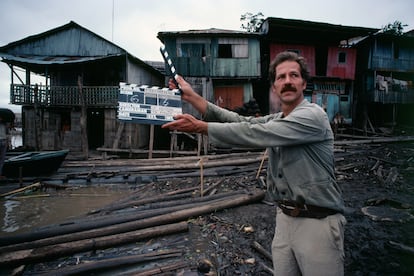

His cinema is visceral and wild. It entails risk; it is unpredictable. One of his most complex and acclaimed productions was Fitzcarraldo (1982), which exemplifies this perfectly. It tells the story of a man obsessed with building an opera house in the middle of the Peruvian jungle — something as risky as Herzog’s decision to film with a crew of 14 people (according to him, one of them was bitten by a venomous snake and had to have their foot amputated), without an assistant or walkie-talkies. They built a dock, created a system of pulleys, hauled a 320-ton ship over the mountains, endured torrential rains, saw the set burned by locals, had two of their aircraft crash, and the director even sold his boots in exchange for fish to feed the crew.

What’s more, Mick Jagger and Jason Robards abandoned the shoot, and Herzog then opted for the eccentric Klaus Kinski, his favorite actor, with whom he had a turbulent relationship — captured in the documentary My Best Fiend. According to the director, Kinski was capable of screaming for an hour with such force that he could shatter glass, and the only reason he was able to direct the film amid that chaos was the depth of his vision and his inner fire. His project and his life merge into one; a commitment that becomes vital in everything he does. On one occasion he threatened to shoot Kinski if he abandoned the set; on another, he urged Joshua Oppenheimer — whom he helped edit The Act of Killing — to keep intact a scene he was thinking of cutting, warning him that otherwise “his life would have been in vain.”

The British documentarian André Singer, who since 1989 has taken part in 17 of Herzog’s films — whether as producer, executive producer, or co-director — highlights via email the director’s “extraordinary talent” for approaching subjects “in surprising and unexpected ways.” He illustrates this with the interview Herzog conducted with Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the USSR, which began with: “Mr. President, I am German, and probably the first German you ever met wanted to kill you,” alluding to when the Soviet leader refused to cooperate with East German president Erich Honecker, which led to the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Jake Friedman, an artists’ representative and admirer of Herzog, shared in person an anecdote that also captures the original, irreverent, and refreshing perspective that defines everything the director does. When Friedman was introduced to him and mentioned that he lived in New York, Herzog (who lives in Los Angeles) replied: “Nothing has ever happened in New York! The most important things have always happened in Los Angeles.” Friedman says that the comment left him so flabbergasted that he didn’t dare say anything else.

Singer also highlights the director’s ability to visualize and hold an entire narrative intact in his mind before turning on the camera. “In 2008, Sky Arts asked Herzog to make a short film about the aria O soave fanciulla, and Herzog, who had just read a book about the Mursi tribe in Ethiopia, had a vision: to bring together young couples from that tribe who would look into each other’s eyes and then turn their backs and walk away. A few weeks later, we camped in the Ethiopian wilderness and shot a hypnotic short, exactly as he had imagined it from the beginning.”

The director’s unique and passionate vision inspires respect, admiration, and fanaticism among professionals across disciplines. “Every day I thank God for living in the same era as Werner Herzog,” said Jerry Saltz, art critic for The New York Times, during Herzog’s presentation at the 92NY.

Herzog is the father of three children, and his third wife is the photographer Lena Pisetski, 28 years his junior, who says that during their first year together she had no idea about his career (he told her he was a stunt coordinator). They have been together for three decades.

Both professionally and personally, Werner Herzog continues to challenge reality with the same conviction: that beauty always tells the truth.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.