‘A colossal jerk has died’: when celebrity obituaries are not kind

The jaw-dropping article in ‘Rolling Stone’ to cover the death of Henry Kissinger once again brings to the fore one of the most striking journalistic subgenres: the obituary in which the deceased does not exactly look good.

Henry Kissinger, former U.S. Secretary of State under presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, Nobel Peace Prize winner, and a widely documented instigator of human rights violations in Latin America and Asia, died last week at the age of 100. Journalist Spencer Ackerman, author of his obituary in Rolling Stone, will not miss him. “Henry Kissinger, war criminal loved by the American ruling class, finally dies” was the headline with which Ackerman dispatched the politician. In the very first paragraph, just in case there was still someone waiting for a laudatory comment in the text, the author recalled the figure of the white supremacist Timothy McVeigh, the murderer with the highest number of confirmed deaths (168 people, including 19 children) executed by United States, to then point out: “McVeigh never remotely killed anywhere on the scale of Kissinger.”

The article, in addition to reporting extensively on Kissinger’s life and work, as well as the approval members of both the Republican and Democratic Parties gave him over the decades, dispensed with etiquette on a day when many others chose to honor the deceased’s supposed statesmanship and negotiating skills in the context of the Cold War. The satirical newspaper The Onion, also published the ironic tribute: “The Onion remembers Henry Kissinger, seen by some as a bit of a Grinch,” a parody of extreme lukewarmness with which certain public figures were reacting to the death of someone considered responsible for the establishment of military dictatorships in Argentina and Chile and the systematic genocide of left-wing political groups, among other crimes.

Talking about a deceased loved one, reviewing all the good things they have left in their wake, and honoring their memory are actions that allow you to cope with grief. Obituaries like the one in Rolling Stone, the satire in The Onion, or memes like the one about Death finally claiming Kissinger — which has put an end to other memes of Death playing with a claw machine and wondering, “Is Kissinger even in here?” which were shared every time a younger, more appreciated celebrity died — lead one to wonder if, in the case of people with a legacy of terror behind them, there is also something cathartic about savoring certain losses.

Dr Nigel Starck, professor at the University of South Australia and author of the book Life After Death: The Art of the Obituary (2006) tells ICON that obituaries about infamous figures “offer readers the satisfaction of confirming that a life that had caused discontent in society has come to an end.”

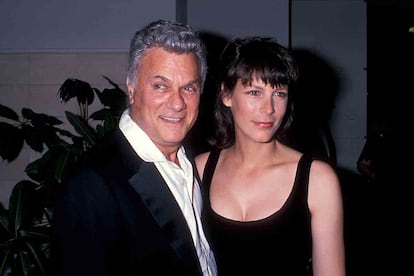

“The main newspapers famous for their quality journalism have never allowed religious sentiment to influence the content of their obituaries,” declares Dr. Starck when asked if a certain protocol of respect for all recently deceased should be assumed in the media as part classic of the rite. The academic affirms that there is “a sustained tradition of hostile assessment,” which was promoted with renewed force in the 1980s “as part of the contemporary predilection for candor, fueled by the freedom of a philosophy mors omnia solvit [death extinguishes all obligations].” An example that Dr. Starck cites is that of the obituary that Graeme Leech, writing in The Australian, dedicated to the actor Tony Curtis when he died in 2010. The journalist described Curtis as “stingy”, “tactless” and displaying “regrettable behavior” and detailed his habit of accepting bets and refusing to pay them. “The tone [of the article] could have been the subject of legal action if the person had been alive,” the professor believes.

Another famous case that he mentions is that of the obituary in The Times of the terrorist Mohammed Atef, military chief of Al-Qaeda and one of the planners of the 9/11 attacks. As his death in November 2001 coincided with that of war hero Hugh Verity, a British pilot who helped the Resistance in Nazi-occupied France. The editors thought it would be interesting to frame both obituaries on the same page, in order to reinforce the contrast between the lives of one and the other. To complaints from many readers about its coverage of Atef, the editor-in-chief pointed to the precedent of Hitler’s obituary in The Times in 1945. In a letter, another reader responded: “At least Hitler was an army general. He wore a uniform and he fought with decency in the war.”

I like you, but six feet underground

In his poem Obituary with cheers, the Uruguayan writer Mario Benedetti invited “the innocent” and “the victims” to celebrate the death of a “piece of shit” with “a black soul.” It was widely circulated on social media in 2004 when former US President Ronald Reagan died and it was misinterpreted that the author had just composed the verses for the occasion. It would happen again two years later with the death of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, but, in fact, it had been published in 1963 (although, in an interview in El Clarín in 2007, Benedetti gave his approval for the Chileans to appropriate it to use against Pinochet). The poem does not state who the deceased in question is; moreover, it specifically recreates the need to enjoy the departure for good of someone who was presumably horrible and whose death has made the world a better place: “it’s time to celebrate / not to tone it down / remember, not just anyone has died [...] don’t forget this dead man / was a real S.O.B.”

The film director Fernando Colomo must have reasoned something like this when in 1991 he penned one of the most famous obituaries in Spanish journalism for EL PAÍS. Let’s rest in peace, was written for the disappearance of the actor Klaus Kinski, accused multiple times of sexual abuse. Colomo had worked with Kinski on Star Knight (1985). Filming was turbulent due to the German actor’s behavior. He attacked several of his colleagues and terrified the team. “A lot of people thought he was crazy. I do not see it that way. He was a rude, spoiled child. If he was an old person, he would only be called a son of a bitch. But now he has died and left us. Let us rest in peace,” wrote the filmmaker. Asked again about the issue in 2021 in Ctxt, Colomo reaffirmed: “He was a son of a bitch. “I wouldn’t write that obituary now, because I’m older, but I didn’t exaggerate anything.”

Outside the more or less official channels of the mainstream media, social media has also allowed individuals to channel specific euphoria. One example is the LGBTQ+ community’s reaction to the 2013 death of Margaret Thatcher, former prime minister of the United Kingdom between 1979 and 1990. Thatcher spearheaded the legislation for what is known as article 28, which prohibited the “promotion of homosexuality” and implicitly associated it with pedophilia. An image of the conservative leader’s grave with stains and the sticker “A transgender person peed here” went viral, as did the song Ding-Dong! The Witch is Dead, from the musical The Wizard of Oz (1939), rose to number 2 in the UK’s Top40 of the most listened to songs in the country in the week of her death.

When it comes to welcome deaths of homophobic people, it’s hard to find a more eloquent obituary than the one David von Drehle dedicated to Fred Phelps in Time magazine in 2014. The founder of Westboro Baptist Church and author of the slogan “God hates faggots,” Phelps managed to finally anger everyone when he decided to systematically interrupt the funerals of American soldiers who fell in Iraq and start spouting his theories. Thus, he received an obituary to match. In only the first sentence he was called a “colossal jerk” and the article celebrated that, at least, the media attention received by the nefarious character had served to turn on the spotlights that “illuminated his fall.”

And on a more anonymous level, the obituary that Dolores Aguilar’s family dedicated to their deceased relative in August 2008 has become a model for children with nothing to thank or celebrate their parents for. Plagiarized ad nauseam, the text said: “Dolores had no hobbies, she contributed nothing to society, and rarely shared a kind word or action in her life. I speak for the majority of his family when I say that her presence will not be missed by many, very few tears will be shed and no one will mourn her passing. (...) We will only miss what we never had: a good mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother.”

Whether you die young or old, you should remember that nothing lives on like an ugly obituary.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.