Jemima Kirke: ‘How could a Jew be in support of this kind of murder in Gaza when our identity has been defined by the Holocaust?’

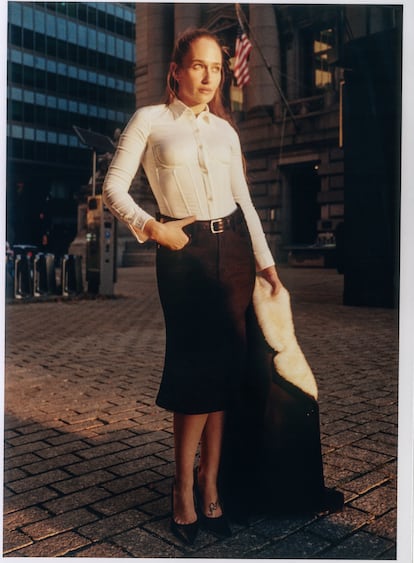

Between nostalgia and the vertigo of the contemporary, the actress who played Jessa on ‘Girls’ narrates her own mystique, radiating indomitable charisma

Jemima Kirke answers the telephone at her home in Brooklyn on a sleep deficit. She stayed up late the night before memorizing her lines for Law and Order: SVU. “I’m going to be a villain,” she says about her role on the most-popular police drama in the country, a series so legendary that writer Carmen Maria Machado wrote a fabulous story in its honor.

At 40 years old, if there’s one thing that suits this multifaceted Londoner raised in New York, it’s playing the villain. She radiates an aura matched by few. Half mythological siren, half femme fatale from 1990s noir, Kirke is fiercely magnetic, allergic to rules, capable of hypnotizing and unnerving anyone in her path. The daughter of Simon Kirke, drummer of the super-group Bad Company, and Lorraine Dellal, interior designer and collector of vintage fashion (“I love shopping, I have good taste, for a long time, the word ‘vintage’ really bothered me,” Kirke says. “I’m like, it’s all clothing, right?”), she is also the sister of actress-singer Lola Kirke and Domino Kirke, a vocalist and doula married to the actor Penn Badgley.

The fact that her Wikipedia profile has so many blue hyperlinks might suggest that her carefree, fearless demeanor comes naturally. But, as she explains in the interview, she has also worked hard to cultivate her mystique. And she has perfected it to the extent that even hearing her husky voice on the other end of the phone is impressive. It’s not every day you get to talk to Jessa Johansson, the character who “looks like Brigitte Bardot with an ass like Rihanna,” as she was described in a line from Girls, the series that catapulted her to fame after studying painting, thanks to her close friendship with its creator, Lena Dunham.

Kirke didn’t stop with the prodigiously coiffed, chaotic icon who had all millennials identifying with Girls at the beginning of the last decade. Now the face of Galician brand Bimba y Lola, she also worked on the series Sex Education and the TV adaptation of that other encapsulator of contemporary femininity, Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends.

Beyond those key roles in this century’s pop culture, Kirke, who also directs music videos, is a popular influencer. Her advice, doled out via Instagram stories and as concise as it is accurate, has led her to become a goddess worshipped by young women mired in ruminations on self-image. Be that as it may, in the end, she confesses, all charm is a matter of method.

Question. Those of us in our forties wanted to be Jessa, and now twenty-somethings idolize you for the way you tell it like it is on Instagram. What does it take to be so charismatic?

Answer. A lot of people have a sort of mystical attitude that people envy. I think the key is being aware of it. When you’re aware of it, you can give the people what they want. That is one side of me, of course, and there’s a side of me I would never show to the public, because it’s private.

Q. “I think you guys might be thinking about yourselves too much” is your now-classic phrase from an Instagram story in which you were responding to a user asking for advice on behalf of young people who vastly overanalyze themselves.

A. When I wrote it, there was a moment where I was like, what does this mean? Is this going to be a no? Even if it is a bit mean, people seem to not mind it, coming from me. I write honestly, but I try to filter it through this sort of persona that you guys have given me. People think that outside of Instagram, I’m wild and free-spirited and living by the beat of my own drum, and all of that. But I’m pacing up and down in my house just as much as anybody, on my phone.

Q. You hide it very well.

A. Social media is a very sanitized, curated version of me. I believe it is an art form. You choose what you want them to see, but you can’t control how they see it, because people are smart. There’s this line that Doon Arbus, the daughter of Diane Arbus, who said something like, that in an effort to hide what we’re insecure about, we often end up revealing it more.

Q. Is that why you don’t talk about politics online?

A. Instagram is a lot of noise, and everything sort of becomes one thing. We’re watching children be mutilated in Gaza and then we scroll to the next thing and it’s Bella Hadid or some influencer. It’s insane that we can literally scroll from a genocide to a tradwife, and our minds can actually make that jump. It says something about us, and I feel overwhelmed by it. I know people who think it can be a real place for genuine expression and to make change, but I don’t see it that way. I did a couple times, and I got misinterpreted so quickly [a reference to when she asked for donations to the Middle East Children’s Alliance to support families and children in Gaza.]

Q. What happened?

A. I got so much hate. As a Jew, it’s horrific what we’re seeing. How could a Jew be in support of this kind of murder when our identity has been defined by the Holocaust? They’re killing all these children, and I feel so strongly that I don’t like to push it in Instagram, which is really where — it’s just the one side of me.

Q. It seems like everyone is re-watching Girls. What changes have you noticed between this generation and the one that watched it when it first aired?

A. I don’t have much of a relationship to it. Especially over the years, I get further and further from it. But there has been a resurgence of people loving the show, which is frankly great for me, and great for my ego. I do get people approaching me all the time. The neighborhood that I live in is very young, so it happens every day.

Q. What do they say?

A. It’s interesting that some people love Jessa, like they want to be like her, and then some people really think she’s awful. I think it depends on your values. She’s just as awful as the other characters, she’s just as flawed and cringy, but what that character has that maybe others don’t have is a mystique and a carefree thing that works in her favor. That’s what’s true for me, I have this great secret weapon that works great with some people and not with others. For the most part, it’s really flattering. I think I appreciate the series more now than I did then.

Q. Lena Dunham has said that you wanted to quit the show in the second season, and Allison Williams, who plays Marnie, has spoken about how the online criticism took its toll on the cast. Is that what made you want to leave?

A. My first instinct was to reject the role. I didn’t want to be famous, I signed up to get paid. I know what Allison was talking about, but I wasn’t really aware of how it was being received. Not because I was so cool and I didn’t care, I just wasn’t really thinking about how it was being received. People told me, and at first I didn’t believe them. I thought they were just blowing smoke. I know Allison was paying attention to that stuff because she was more dedicated to the industry.

Q. Two of the series you’ve worked on, Girls and Conversations with Friends, were created by Lena Dunham and Sally Rooney, two of the authors behind the paradigm shift that the feminine ideal has undergone this century. Nowadays, stories have become much more flat and gender-essentialist — it seems like it all comes down to which man the protagonist will choose. Are we seeing a backlash?

A. Materialists was terrible. I don’t know where all this is coming from and honestly, it’s really hard for me to watch TV now because like a lot of people, I feel flat. There’s so much of it, we get numb. We can’t feel anything and nothing’s really stimulating and there’s just too much, which then gives us anxiety. I just watch cable TV, and I love radio, and I love commercials. I like not knowing what’s coming up. I used to be obsessed with studying different pockets of rock ‘n’ roll, ska music, and punk. Maybe it’s because I got older and I care less, but I just prefer being told what to listen to [or watch].

Q. Compared to the New York of Girls, nowadays, the shows and movies that play out in the city are more about professional ambition and money. The city is a much colder, more cynical place. It doesn’t really make you want to live there.

A. They’re focusing more on the struggles of living here than the wonder. That is funny, isn’t it? I don’t really know why that is. It might be that there’s a reason for Americans to be kind of depressed right now. I think generally people get outside and do less stuff, so maybe they aren’t embracing the city the way we used to, due to social media.

Q. Is that different from the way it was before?

A. I mean, I’m always depressed. People are very upset about phones, but it’s quite boring to be talking about how “we used to be doing this” and “everyone was happier before the phones.” I’m like, no, they weren’t. Things were different, but they’re always different 10 years ago. But yes, it is true that the work culture has gotten worse.

Q. Nowadays, even Leonardo DiCaprio has to post short videos to social media and appear on podcasts talking about things that have nothing to do with the movie he’s starring in. Are you sick of this new panorama when it comes to promotion?

A. You have to have an Instagram and a social media presence. The podcasts are tiring to me. Everyone has the same fucking podcast. You’ve got nothing, we’re not interested. What’s sort of interesting is that you know, people are signing up to do podcasts and just talk loosely like that, but we all have a strategy.

Q. You’ve said that your sister Lola was unhappy about your success on Girls because she was the actress and you were were supposedly the sister who painted. What’s it like having artistic siblings?

A. You don’t get to pick your family. There are times when the members of your family are not people that you would ever be friends with. And at times, I feel that way about my sister. At times I’m like, “My God, if you weren’t my sister, I would just like, never call you.” But most of the time, I’ve got really cool sisters. Lola is one of the boldest people I know, she doesn’t hesitate, and she’s hilarious, the funniest person I know. I was so mean to her as a kid — all sisters can be mean to each other. When I had my own kids, it really made me think about my relationships with my sisters and my parents, and I really regretted how mean I was. I could understand how damaging that could have been. But apparently, it made her into this wonderfully brilliant person. Maybe that’s because of me.

CREDITS

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.