The financial scandal that rocked Franco’s Spain and ended with a suicide in Lausanne

Historian Enrique Faes uncovers a case hidden in the archives for 60 years: a real-life detective tale involving tax evasion, secret codes and a Swiss bank employee who sought out wealthy clients in post-war Spain

His body was lying in the double bed of the apartment he and his wife had moved to when he had to leave his hometown because he had lost his job. Georges Laurent Rivara shouldn’t have died in Lausanne, nor should his last job have been as a lingerie salesman. He died on September 6, 1962, at the age of 46. It’s most likely that he killed himself. He had lived most of his life in Geneva and had dedicated himself early on to the banking business. His nightmare had begun four years earlier in Spain. From the shadows, he had been the instigator of hundreds of financial crimes. The Rivara case, which broke out in late 1958, was one of the major financial scandals of the Franco dictatorship in Spain.

This Thursday, a new book documenting the story will hit the bookstores: El agente suizo. Fuga de capitales en la España de Franco (or The Swiss Agent: Capital Flight in Franco’s Spain). Although the plot sounds right out of a detective novel, every element has been thoroughly documented, says its author Enrique Faes, a professor of social history and political thought at the distance university UNED. The historian’s research began with the 20 boxes of the Rivara case summary. “I initially looked for it in the Bank of Spain’s archives, because the documents from the Spanish Institute of Foreign Currency must have been there, but I finally located it instead in the Economic Crimes Court Collection, in the General Administration Archives,” he explains. He also accessed documents from the Swiss Ministry of the Interior held by the Archives Fédérales (Federal Archives). Besides that, he consulted 10 additional archives. And just when he thought he had reached the end, he even managed to interview the protagonist’s son.

In the midst of the Spanish Civil War, Rivara began working at the Banque de Bilbao en Suisse — a financial entity created in 1933 so clients of the Spain-based Banco de Bilbao could make deposits in Switzerland. The institution eventually became part of the Société de Banque Suisse. It was 1951, and Rivara kept his position. Two years later, he made his first trip to Spain, which he would repeat in the following years with a doubly shady objective: first, to attract Spanish clients and convince them to open accounts in Switzerland without declaring them to the Spanish state, and then to visit these clients in person periodically to inform them of the status of their savings, securities and investments.

Since the business was illegal, the company sent these clients an internal note urging them to take extreme precautions. “It was almost an abbreviated secret agent’s manual,” notes the 48-year-old historian. There were no documents with clients’ names written on them, and Rivara avoided being seen in public with them, and watched out for wiretapping. To be able to do his job, he equipped himself with a code system and had a few trusted people with whom he could leave documentation to be sent or received by mail.

“It was a widespread practice,” Faes says. “Generic testimonies from other bankers confirm this.” The historian names two more agents, one of them working with wealthy Basque clients. “It was an accessible and lucrative business.”

The Rivara case begins on November 30, 1958. An elegant man who spoke good Spanish, he walked out of Avenida Palace, his usual hotel when he stayed in Barcelona. Rivara got into his Opel Olympia Rekord and started it, but a vehicle blocked his way. An inspector from the Criminal Investigation Brigade opened the door, got in, and ordered him to drive to the Vía Layetana police station. This was a feared location because of the torture that routinely took place there. Rivara didn’t suffer any of it, but he was not able to keep silent either. The surveillance had been exhaustive. “I was surprised to discover a certain sophistication among the Francoist police who fought against financial crimes; they were the first class of criminology students,” explains Faes. At the police station, after just a few questions, Rivara broke the banking secrecy he was bound to by law in his home country.

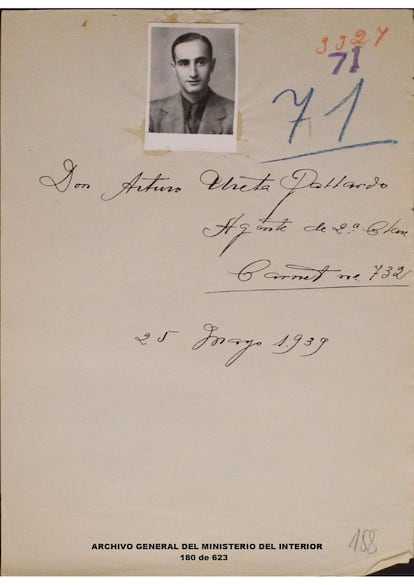

Who tipped off the Barcelona Criminal Investigation Brigade to start following him? The hypotheses ranged from a spurned lover Rivara might have had in Barcelona, to the commissions the police might charge depending on the eventual revenue the case brought to the state. The investigation was led by the highly professional Superintendent Arturo Ureta. His men searched the car trunk and found the envelope containing evidence that Rivara was working with client lists from Madrid, Bilbao, and San Sebastián.

For the clients in Barcelona, investigators found out who to call: the prestigious notary Federico Trias de Bes. They went to his office, from there they asked him to call the police station and speak with Rivara, and it became clear that their alibi of a company they were about to set up together wasn’t going to fly. The notary handed over the list of Barcelona clients. There were hundreds. Quite a few of them trusted their fate to Garrigues, a law firm with well-established international connections.

The case soon reached the desk of José Villarías Bosch, a judge for economic crimes whose work was carried out under a law passed during the Civil War aimed at supporting a self-sufficient war economy. Rivara was transferred to Madrid for further questioning at the General Directorate of Security (DGS). The investigation progressed rapidly in just a month, and Swiss diplomacy had little time to react. Villarías opened case files for each of the names that appeared on the lists.

On December 12, Franco himself brought up the matter in his monthly meeting with his ministers. He asked the Minister of the Interior to report “extensively on the police action that led to the investigation of these facts.” What Minister Camilo Alonso Vega said is crossed out in the minutes of the meeting. It is also known that the Ministry of Commerce, headed by Alberto Ullastres, had explored the possibility of granting amnesty to the tax evaders in exchange for the repatriation of capital that the public coffers urgently needed. The evaders argued that they had opened these accounts abroad to gain easier access to foreign currency. But the proposal of a tax amnesty was never discussed.

Political and media control of the case went beyond control. The international press reported on it, using exaggerated figures. And then something happened that made it completely exceptional. On March 9, after the sentences were signed, the names of the 872 people implicated in the scandal were published in the Official State Gazette. Everyone could — and still can — find out the fine that was imposed on the tax evaders (it was less than expected) and how much money they had hidden away in Geneva.

After legal consultations, Faes has been cautious in naming names: data protection laws and the right to one’s honor have been used deliberately to restrict the study of the past. But the Official State Gazette (BOE) is posted online. And the list of tax evaders draws a possible map of what the geography of Spanish wealth was like in the late 1950s. They range from executives from the companies Grífols and Dragados to the father of former Catalan premier Jordi Pujol, enriched by currency smuggling; there were high-ranking officials of the Franco regime, and executives of the Swiss company Nestlé in Spain. The Société de Banque Suisse’s motto “trust, security, discretion” had been shattered. So had Rivara’s future when he returned to Switzerland at the end of 1959. Although the company paid the fine of more than one million pesetas, he lost his job and his reputation.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.