The story of how a 1709 Stradivarius violin, looted during the Nazi era, resurfaced in Japan

A report by specialist Carla Shapreau illustrates the obstacles to restitution of musical heritage looted during the Third Reich

In the 1920s, the mansion of the Jewish banker Franz von Mendelssohn in the leafy Grunewald district was a prominent center of Berlin’s cultural life. The great-nephew of the composer Felix Mendelssohn organized chamber music evenings there with renowned pianists such as Artur Schnabel and Edwin Fischer, as well as celebrated music lovers, including Max Planck and Albert Einstein. A partner in the Mendelssohn & Co. Bank, Franz owned a valuable collection of antique instruments, among them the Stradivarius Mendelssohn violin from 1709, which he gave to his daughter, the violinist Lilli von Mendelssohn-Bohnke. She played it in the family quartet with her father and her husband, the composer and violist Emil Bohnke.

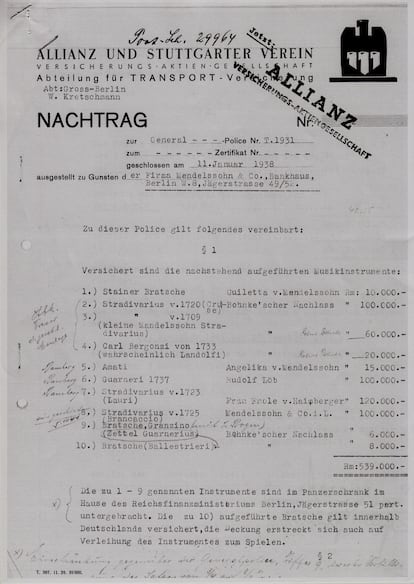

A tragic car accident ended Lilli and Emil’s life prematurely in May 1928, leaving behind three young children. After the tragedy, Franz placed the instrument in a safe deposit box at his own bank, after obtaining a certificate of authenticity in 1930. The Nazi rise to power in 1933, his death two years later, and the liquidation of the bank, considered a Jewish business by the Third Reich, meant that the violin ended up in the former Deutsche Bank headquarters on Mauerstrasse. It was apparently stolen from there in 1945 by the Soviet occupying forces, although it is also possible that it was taken away by the Nazis before the fall of Berlin.

This valuable violin has recently been located in Japan, where it was going under another name, Stella. A preliminary report prepared by expert Carla Shapreau of the Institute of European Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, and published on the website of her project dedicated to the restitution of musical heritage looted during the Nazi era in Europe, has revealed another fascinating story about a Stradivarius that was plundered during the Third Reich.

The plot might evoke scenes from François Girard’s famous film The Red Violin. However, there are studies on Nazi musical plunder, along with well-documented stories of the theft, sale, and reappearance of Stradivarius violins, which have informed the plots of several novels. Willem de Vries’ book on the musical cell of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, the Nazi unit tasked with confiscating Jewish heritage and eliminating Jewish culture, is already a classic. Meanwhile, Toby Faber’s monograph Stradivarius combines an entertaining narrative about the life of Antonio Stradivari with the adventures of five of his violins and a cello. More recently, Alejandro G. Roemmers wrote a novel whose plot begins with the real-life 2021 murder of luthier Bernard von Bredow and his daughter in Paraguay, and goes on to construct a historical murder mystery with a Nazi undertone around the supposed “last Stradivarius.”

Yoann Iacono’s novel Le Stradivarius de Goebbels (in the original French) focuses on the gift that the Nazi propaganda minister gave to the young Japanese violinist Nejiko Suwa in 1943: an instrument stolen from a French Jew in a concentration camp. This true story was recounted by Shapreau herself in The New York Times in 2012, as an introduction to her ambitious project to recover musical treasures plundered by the Nazis, which has been much less researched than the plundering of fine art.

Shapreau’s article clearly demonstrated the difficulties of this type of study. The scarcity of documents and the lack of cooperation from the owners generate controversy and multiple obstacles to research. In fact, the violin given by Goebbels to Suwa is now owned by her nephew, who has refused to reveal the characteristics of this dubious 1722 Stradivarius. Shapreau’s results regarding the 1709 Mendelssohn have been very different, as in this case there is abundant written and photographic documentation, allowing for unequivocal conclusions.

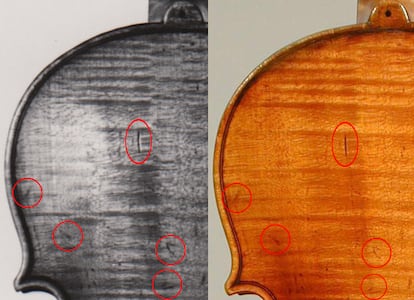

“In June 2024, I discovered the whereabouts of that stolen Stradivarius thanks to a tip indicating the violin could be in Japan,” explains Shapreau, who answered all questions about her investigation to EL PAÍS via email. She first scoured the web unsuccessfully for a 1709 instrument known as Mendelssohn Stradivarius. She then compared a black and white photograph taken in 1930, as part of the certificate of authenticity, with all the Stradivarius violins preserved in Japan. It was then that she found surprising coincidences between the marks and scratches that appeared in that image and those of a 1707 Stradivarius called the Stella. This instrument had been exhibited in 2018 along with 20 other Stradivarius violins at the Mori Arts Center Gallery in Tokyo, and was owned by the violinist Eijin Nimura.

The story continues with the investigation into the past of the 1707 Stella. The first reference to this instrument appears in Paris in 1995, when a Russian violinist brought it to the famous shop of luthier Bernard Sabatier, on the Rue de Rome, to sell it. According to the musician — whose name has never been revealed — he had purchased it in 1953 from a German dealer in Moscow. Sabatier authenticated the violin in London with the help of renowned expert Charles Beare, who determined that it had been made in Cremona between 1705 and 1710, under the supervision of Antonio Stradivari and with the participation of his son Omobono. The handwritten label inside made it difficult to determine whether the date was 1707 or 1709. The violin subsequently passed through two owners, and in 2000, it was auctioned at the prestigious Tarisio auction house in New York, where Jason Price studied and photographed it.

Price also responded to EL PAÍS via email and confirmed Shapreau’s recent discovery: the Stradivarius Stella and the Mendelssohn are, in fact, one and the same instrument. This expert is not only the founder and director of Tarisio, but also the head of the Cozio archive, which boasts the most comprehensive database of antique stringed instruments and bows. Curiously, the name Stella appears for the first time in a report dated March 31, 2005, detailing its provenance — “it was in the possession of a noble family living in Holland since the time of the French Revolution” — and the origin of its nickname: an ancestor called it Stella because its sound “shone like a star.”

But Shapreau has confirmed that the document is a forgery. In the latest update to her report, dated August 7, the two officials cited denied their authorship. Both Bernard Sabatier — whose name appears as a signatory — and Austrian dealer Dietmar Machold — whose letterhead appears on the document — reject the veracity of this declaration of provenance of the Stradivarius Stella. The instrument was sold in 2005 to Japanese violinist Eijin Nimura, a UNESCO Artist for Peace, who has not agreed to collaborate with this investigation or reply to this newspaper.

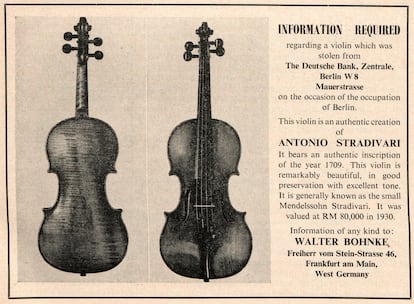

The heirs of the Mendelssohn-Bohnke family have always fought to recover this instrument. According to Shapreau’s report, Walther Bohnke, Lilli and Emil’s eldest son, began spreading the word about the theft in various specialized media, such as The Strad magazine, where he published an advertisement accompanied by a photograph in 1958. He not only gathered numerous testimonies until his death in 2000, but also requested help from Interpol and managed to have the claim incorporated into the database of the German Foundation for Lost Art, which documents cultural objects confiscated as a result of Nazi persecution.

Today, the Mendelssohn-Bohnke children are deceased, but David F. Rosenthal, principal percussionist with the San Francisco Ballet Orchestra, is acting as the family representative, as he is the grandson of Lilli von Mendelssohn-Bohnke and the great-grandson of Franz von Mendelssohn. He also replied to EL PAÍS via email. “I grew up hearing about this violin and its theft, and it always upset my mother [Lilli Bohnke-Rosenthal] when the subject came up. Most of us in the family thought the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin had been destroyed since its theft from our family’s bank safe in Berlin as a result of Nazi era events. My uncle Walther Bohnke was among those who never gave up trying to find it though,” Shapreau quotes him as saying in her report. “It was always known in our family as my grandmother Lilli’s violin, and it is a vital piece of the Mendelssohn-Bohnke family’s heritage. It connects us to our past in very profound and emotional ways.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.