The mysterious death of the ancient priestesses who wore 270,000 seashells

A group of archaeologists describes details of the 5,000-year-old burial of 20 women adorned with perforated beads

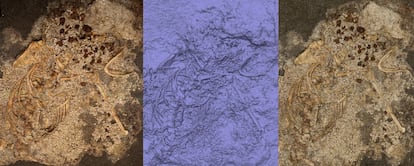

There is nothing like it in the archaeological record: more than 20 human remains in a circular burial, all women, with those at the center surrounded by thousands and thousands of small white beads, likely once part of their clothing.

This is the site of the Tholos of Montelirio, near the Spanish city of Seville. After years of work — with each piece cleared one by one — a recent study published in Science Advances estimates the total number of beads, likely part of tunics, skirts, or sashes, at over 270,000.

The researchers also determined that these items were made from 800 kilograms of various species of mollusks. A previous study on the bones had found the highest concentrations of mercury recorded in scientific literature. The combination of the largest number of seashells in a tomb and the exceptionally high levels of metal make Montelirio an extraordinary site, where women — who must have had a special significance — were buried approximately 4,800 years ago.

“It is impossible to count them; there are more than a quarter of a million. What we’ve done is estimate,” says archaeologist Leonardo García Sanjuán from the University of Seville, referring to the perforated beads. To reach that figure, the team took a sample of 1,000 washed beads and weighed them. Using the rule of three, they arrived at an estimate of 270,769 white beads.

“The next known tomb with this type of bead — the next largest collection — is from a site in the United States. It’s the largest ceremonial complex known in northern Mexico. There, a tomb belonging to someone considered socially important contained 30,000 beads. Beyond that, the known tombs contain collections of 5,000, 2,000, or 1,000 beads,“ says García Sanjuán.

Although some beads are made from ivory or other stones, 99% are crafted from various species of scallops and cockles. Through a series of experiments designed to replicate their production, scientists estimate that around 800 kilograms of these bivalves were required.

“Scallops are now known as the symbol of the Way of St James, but in ancient times, they represented Aphrodite/Venus. It’s clear that in the pre-Christian world, the scallop, its shell, was a symbol of femininity. It is a symbol of goddesses, who are basically the goddesses of fertility,” says the archaeologist.

There is another detail that makes this site so unique. The burial consists of two chambers and a 40-meter-long corridor. Remains of 26 individuals were found in the dolmen, with the majority (20) located in the large chamber, 17 of whom were women. The gender of the other three could not be determined.

The perforated beads were found around a group of these women, arranged in a specific manner. One woman, likely covered in a tunic made of seashells from neck to legs, seems to have held particular significance. She was discovered with her hands raised, as though in prayer, aligned with a stele that was illuminated only once a year during the summer solstice. On this day, a thin ray of sunlight would cross the entire corridor until it reached the women.

“This is very special, because there are no men, no old men, no elderly women, and no children. This tomb doesn’t represent a snapshot or a cross-section of society. It’s a very select, special group,” says García Sanjuán.

Radiocarbon dating further adds intrigue to the find. All the women appear to have died within a relatively short time frame. Carbon-14 decay begins immediately after death, as the radioactive isotope breaks down into stable nitrogen-14. However, this dating method has limitations, as the “clock” isn’t extremely precise, with potential variations of around a few years in either direction — in this case around 25. This means the women wearing the beaded robes may have died in a single event or over the span of several years. The shells, which were also dated, don’t provide enough clarity to definitively determine the timeline. However, they do suggest that the shells were gathered just before the women’s deaths.

Marta Díaz-Guardamino, an archaeologist from Durham University in the United Kingdom and co-author of the research, emphasizes that there is no certainty regarding the exact moment the shells were collected. “Radiocarbon dates only determine when the bivalve died,” she explains.

With this caveat in mind, she points out that the mollusks “provide a time range within which all these processes could have taken place — the death of the bivalve, its collection, and the manufacturing of the beads.” This period could span anywhere from one or two years to as much as 200 years. For Díaz-Guardamino, this means it cannot be definitively stated that, just as with the women, the collection and manufacturing happened in a single event. However, they cannot rule out that possibility either.

There is similar uncertainty over García Sanjuán’s hypothesis that the women wore their sea bead outfits during ceremonies. It’s also possible, however, that the beads served as their shroud, worn only for burial. “We did observe wear on some of the beads, but it seems to be the result of erosion, caused by the substances they’ve come into contact with, rather than from actual use,” explains Díaz-Guardamino.

Mercury in the bones

Adding to the mystery of Montelirio, a 2023 study confirmed that those buried there had unusually high concentrations of mercury in their bones. Today recognized as a dangerous toxin by the World Health Organization (WHO), mercury has been used directly or indirectly for millennia. In nature, it occurs as mercury sulfide in minerals such as cinnabar, a pigment that was used in the earliest cities, like Çatalhöyük, around 10,000 years ago. Later known as Pompeian red, it was responsible for the vermilion color of Roman villa walls. Mercury was also integral to mining, aiding in the separation of gold and silver from other metals. Until the 19th century, it was even used in medicine (and still appears in the Chinese pharmacopoeia) as the primary treatment for diseases like syphilis.

All the women from Montelirio had mercury in their bones. The average concentration in the femur reached up to 95 micrograms per gram of bone, but in 17 of them, the levels were around 500 micrograms.

Raquel Montero, an archaeologist at the University of Seville and an expert on the use of cinnabar and mercury throughout history, co-authored the study that determined the levels of mercury in the bones from the burial site. She explains that these concentrations are extremely high, but comparing them is difficult. “There is no threshold set by the WHO, and it’s not easy to study mercury in bones,” Montero says. What is clear, however, is that the women buried in Montelirio had toxic levels of mercury in their bodies.

“But we don’t know how it got into their bones,” admits Montero. There was cinnabar scattered around the site, she explains: “It was found on the ground, on the bodies, and the walls were painted red, but we don’t know if they also painted their skin.”

Her colleague García Sanjuán believes they may have been painted red and dressed in seashells “in ceremonies that must have been impressive to those who observed them.” In fact, the Valencina complex, where the burial site is located, was a ceremonial gathering place. The study’s authors also note that, in small doses, mercury can induce altered states of consciousness, similar to the effects of ritual drugs. Another possibility is that the women were sacrificed, poisoned with cinnabar, and then shrouded in shells. Several additional studies are currently underway that may help answer these lingering questions.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.