The controversy over displaying human remains, like the ‘giant’ brought to Spain for a king’s amusement

Medical museums are rethinking how they exhibit controversial specimens like the skeleton of Pedro Antonio Cano, a 7-foot man from South America

Pedro Antonio Cano was very tall. So tall that, in 1792, the viceroy of New Granada (present-day Colombia) decided to send the 20-year-old giant and a yellow parrot as gifts to King Carlos IV of Spain. After a dangerous three-month journey across the ocean and eight days by stagecoach through the Iberian Peninsula, a humble Pedro Cano arrived on August 26 at the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso (Segovia, Spain) dressed up as a Hungarian soldier, where he was received by the monarch. The monumental skeleton of this South American man who once inspired the awe of Carlos IV, can now be viewed at the Javier Puerta Anatomy Museum in the Complutense University of Madrid. But institutions worldwide are reconsidering the display of human remains and the Mütter Museum ( Philadelphia, U.S.), one of the world’s largest medical museums, recently removed all images of its vast collection from its website.

Hardly anyone knows that the bones of a man uprooted from his South American homeland are on display in Madrid. Even the museum had forgotten until historian Luis Ángel Sánchez discovered the skeleton in 2017. The researcher was reading an 1833 edition of Don Quijote with an editor’s note about authentic giants that mentioned Pedro Antonio Cano. After sifting through the archives, Sánchez found a story about a towering South American who had settled in Madrid. This man was given a lifetime pension by Carlos IV that was ten times the salary of an average worker. On the morning of August 17, 1804, the newly formed College of Surgery of San Carlos (located in the basement of what is now the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid) was alerted to Cano’s death by clergymen. The surgeons took possession of the giant’s remains and dissected them for display in the institution. His bones were eventually turned over to the Complutense University of Madrid, although they were mislabeled as belonging to a “giant from Extremadura” (western Spain).

The skeleton is impressive. Museum director Fermín Viejo Tirado looks tiny standing next to it. “He’s 2.15 meters [seven feet] tall, like Pau Gasol [the Spanish professional basketball player],” said Viejo. Across the room from Cano’s skeleton is another one, attributed to a Napoleonic soldier. The bones have dark stains from the mercury salts used at the time to treat venereal diseases like syphilis. Displayed nearby are three mummified corpses with grimacing faces and splayed chests spilling out viscera. The three people who were dissected by a surgeon named Pedro González Velasco in the 19th century, had a congenital defect known as situs inversus — their hearts were on the right side of the body.

“Human remains are only exhibited on guided tours so we can tell their story with the utmost respect,” said Viejo. Photographs in the museum are prohibited. “We display Cano’s skeleton because it exhibits a condition called gigantism. He was born at a time when unusual people were viewed as monsters and exhibited as curiosities in circuses and fairs. We cannot make the same mistake,” he said. Viejo doesn’t believe human remains should be sacralized. After all, he says, medical students routinely exhume bones from cemeteries without any controversy about disturbing a human being’s eternal rest.

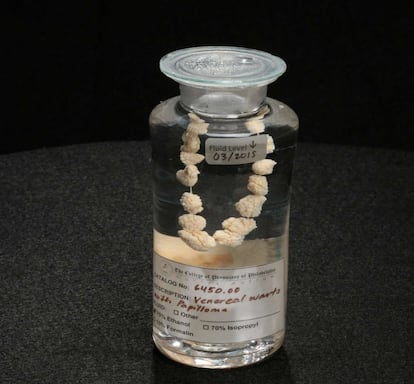

The College of Physicians of Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum has a collection of 1,300 jars with human remains preserved in alcohol, mostly organs with various diseases. Among its more shocking pieces are the brain of the man who assassinated U.S. President James Garfield in 1881, and a 19th-century necklace of genital warts instead of pearls. The museum also boasts of being “one of only two places in the world to house Einstein’s brain,” even though the German-born physicist asked to be cremated to avoid veneration of his remains.

Kate Quinn, director of the Mütter Museum, explains that they have “temporarily” removed videos from their website so a committee of experts can review them individually and determine “whether they conform to best practices regarding the respectful display of human remains.” Quinn says respectful display has three elements: legitimate ownership of the remains, consent to display them, and providing the proper context for educational purposes. “These are challenges for all museums that exhibit human remains,” she said.

Pedro Antonio Cano’s skeleton has been misidentified for decades and the museum website still classifies him as an “Extremaduran giant.” The remains of the real Extremaduran giant — Agustín Luengo (1849-1875), a 7-foot-7 (2.35-meter) man from Badajoz — were once on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Madrid. The institution decided to remove all human remains from public display in May 2022, except for the shrunken head of a man decapitated by an Amazonian people known as jíbaros.

Patricia Alonso, curator of the museum’s America and Oceania collections said, “We think that human remains can be exhibited in museums as long as the community of origin is not against it, when they are essential to understanding the topic, and are presented respectfully in the proper context.” Spain’s National Museum of Anthropology has over 4,400 human remains, including skulls, six mummies, and 13 complete skeletons, including one of a Filipino woman. Her bones were brought to Spain in the 19th century by a reckless explorer named Domingo Sánchez, who raided tombs with a shotgun slung over his shoulder.

The placard beneath the only human remains on public display in the museum describes the Shuar (Ecuador) people’s practice of decapitating their enemies, discarding the skull, and shrinking the facial skin using a boiling process. The Shuar abandoned this practice in 1960. The placard also describes how Western collectors’ pursuit of shrunken heads heated up conflicts between Amazonian peoples in the late 19th century and beyond, ultimately leading to more decapitations to satiate this disturbing market. The museum has recently undergone an ethical shift in how it treats human remains, recognizing that these artifacts are more than mere cultural property. Since they represent a deceased individual, the museum now strives to treat them with the utmost dignity and respect.

One of the most remarkable anatomy museums in the world is the Musée Fragonard, established by France’s Royal Veterinary School in 1766 on the outskirts of Paris. Its display cases present two-headed cows, one-eyed lambs, horned horses and all kinds of animal skeletons. But these specimens are mild compared to the museum’s collection of flayed human cadavers. In a dimly lit exhibit room are gruesome corpses with the skin removed by surgeon Honoré Fragonard to teach anatomy in the 18th century. The flayed bodies include a rider on horseback, a menacing man holding a horse’s jaw, and three unborn children labeled “the dancing fetuses.”

The director of the Fragonard Museum, veterinarian Christophe Degueurce, says there has never been any controversy in France over the display of these flayed corpses, not even the fetuses. “The anatomist’s goal was to position the body to provide maximum information — a three-dimensional view of a body in motion so the joints, muscles and blood vessels can be appreciated,” said Degueurce. “It’s imperative that we ensure respect for the human body, which means not turning this into a money-making spectacle. You will never see a Halloween party at the Fragonard Museum.” Degueurce was critical of the touring Bodies exhibition, which is currently in Murcia (southeastern Spain) until June 11.

“Ethical questions arising from the fields of anthropology and ethnology are radically different from those of an anatomy museum,” said Degueurce. “Here, the individual on display only fulfills an anatomical function. The cadaver is ultimately a symbol of humanity, but once it’s dissected, no one can identify any family relationships or ethnic origin.”

Anton Erkoreka is a medical doctor who has been running the Basque Museum of the History of Medicine for the last 25 years. The museum is housed on the Leioa campus of the Basque Country University in Bilbao (northern Spain). With an appointment, you can visit a locked room with more than 400 flasks containing diseased organs, such as lungs with tuberculosis and silicosis, and five fetuses, one of them without a brain. These human specimens were extracted by public hospitals (Basurto and Gorliz) in the 20th century. “We cannot give up these collections just because of a wave of political correctness,” said Erkoreka. “These specimens have been fundamental to identifying the microorganisms that caused pandemics, such as the influenza virus of 1918,” he said. The museum’s Pathological Anatomy and Neurology room is its most popular exhibit.

Human remains identified by name are the most controversial, especially those obtained surreptitiously or unethically. London’s Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons of England decided in January to remove the skeleton of Charles Byrne from its display cases. Byrne, a 7-foot-5 (2.31-meter) man who died in 1783 when he was only 22, earned a living exhibiting himself as “the Irish giant.” Byrne told friends he didn’t want his body dissected, but surgeon John Hunter paid them a small fortune for his corpse. The museum now keeps the skeleton out of sight in storage.

Irishman Cornelius Magrath was also a very tall man. The 7-foot-4 (2.26-meter) man died in 1760 at the age of 24. Evi Numen, curator of the Old Anatomy Museum at Trinity College in Dublin, showed EL PAÍS his imposing skeleton. Magrath died at Trinity College, and the attending physicians decided to keep his skeleton to teach others about the medical condition of gigantism.

“The controversies surrounding these collections seem to have piqued people’s interest in them lately,” said Numen. “Scandals attract attention, and with that comes fascination and a desire to learn. Suddenly, you have more eyes on you than ever before.” The curator worked at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia before moving to Dublin, and was critical of the museum’s decision to remove images from its website. “These collections are very important. It would be very sad if they disappeared and a huge loss for education and research. Honestly, I think we have to ask ourselves: what are the advantages of hiding history rather than discussing it openly?”

Pedro Antonio Cano’s skeleton tells a story of enlightened despotism and colonial domination, of all-powerful monarchs and their peasant subjects. It’s an uncomfortable part of Spain’s history. Every year, only 1,800 people — mostly high school students and retirees — view the bones of the South American giant, misidentified for decades. Fermín Viejo Tirado stands next to Cano’s bones and says once again, “I have no problem with exhibiting human remains, but they must be treated with respect and displayed only if they can teach you something, not just for morbid curiosity. There have to be scientific reasons to exhibit them, not like the 19th century freak shows with giants, dwarfs, ugly men and bearded women.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.